The Promise of Fusion is Real, If it's Properly Funded (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Gregory Scott Jones is a writer who specializes in covering supercomputing. He contributed this article to LiveScience's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

If energy research was an elementary school playground, the study of magnetic fusion might be the kid in the corner all alone, throwing pebbles at the ground with a frown on his face.

An outcast no one believes in, let alone wants to hang out with.

But there's a real possibility that that lonely kid will one day become a CEO, a brain surgeon, or a visionary software entrepreneur. How many times has the next big thing been passed by in the name of popularity?

Driving magnetic fusion

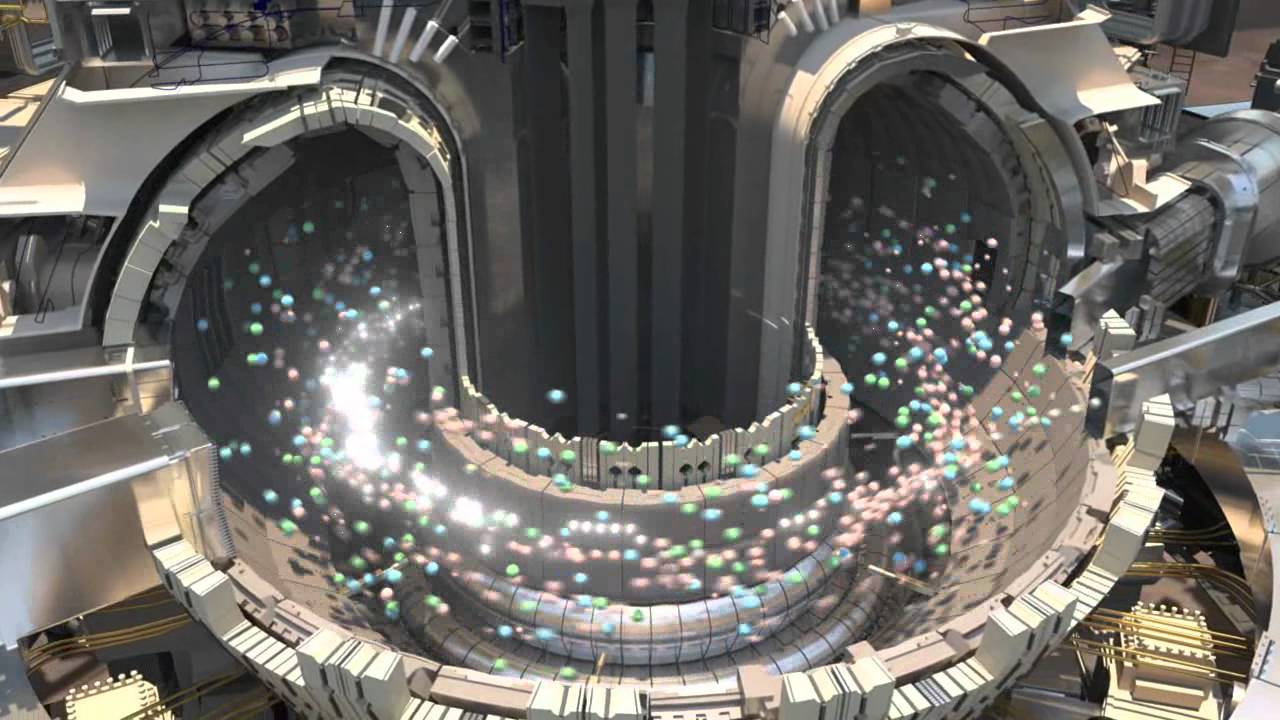

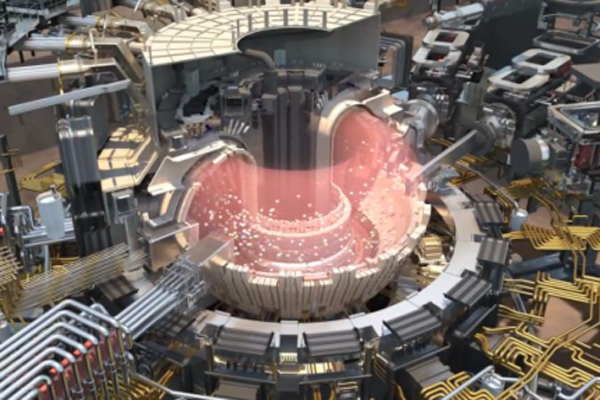

Magnetic fusion is the controversial field that is always, in the words of its naysayers, fifty years away. Basically, by heating the hydrogen isotopes tritium and deuterium to ten times the temperature of the core of the sun, it's possible to create a self-sustaining reaction like the one that fuels the stars in the sky. Possible, but not easy.

If realized, fusion energy could provide the world with an abundant, and relatively clean, energy source. While there are radioactive byproducts, fusion's storage issues pale in comparison to those of fission (think 100 years versus hundreds of thousands).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And the fuel required is basically saltwater for the deuterium, and the tritium can be manufactured during the fusion process. The problem, as is the case all too often in long-term scientific endeavors, lies in the realm of payoffs. The naysayers are there for a reason: The quest for fusion energy has had its hiccups.

Enter ITER, the world's largest magnetic fusion project to date. Currently being built in Cadarache, France, ITER is an agreement among the United States, China, South Korea, Russia, India, Japan and the European Union to build a working prototype for a future fusion reactor to show that actually producing electricity via fusion can be done. Essentially, ITER is the laboratory that will allow researchers to actually monitor, in real time, the fusion energy production process; its goal is to produce ten times the power (500 megawatts) required to start the reaction, for approximately ten minutes. The knowledge gleaned could very well lead to the next big thing in alternative energy: a commercial fusion reactor.

Lately, however, domestic economic realities have been an additional hurdle in an already difficult mission, putting America's commitment to ITER, and fusion in general, in question. America would be wise to make a positive, definitive statement for three basic reasons.

Overcoming obstacles to a fusion future

First and foremost, U.S. investment in ITER is relatively inexpensive. In exchange for less than 10 percent of ITER's construction cost, America is privy to all experimental data and technology and can propose and run experiments on what will be by far the largest tokamak-style reactor ever built. Furthermore, America's national laboratories, universities, and businesses will have the opportunity to design and construct actual ITER technologies.

For perspective consider the Department of Energy's Office of Science FY2014 budget request, in which spending on solar will reach $356 million next year, nearly triple the $120 million budget of ITER this past year. In fact, the combined research budgets for wind and geothermal energy will likely top $200 million in 2014, a proposed budget increase of 57 percent and 62 percent, respectively, from 2012. As far as revolutionary energy technologies go, the road ahead to ITER looks relatively affordable.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, to some degree failure is impossible. While it is certainly feasible that commercial fusion energy simply isn't practical in the long term, huge advances in simulation, superconductors, materials and plasma science (to name a few) will inevitably be discovered in our quest to put a star in a jar. All of these areas represent significant bottlenecks to progress in numerous research and development projects.

Finally, magnetic fusion is increasingly on the research radar of the world's most developed and rapidly developing nations: South Korea currently operates one of the world's premiere tokamaks, K-STAR, and has announced plans to build by 2037 an actual fusion reactor capable of generating electricity; and Germany is developing a design alternate to ITER, called a stellerator, that will put any fusion device this side of the Atlantic to shame. Asia is likewise jumping on the fusion bandwagon. Either all of Eurasia is wrong, or they're on to something. America will fail to follow suit at its technological and competitive peril.

After all, if America is to continue to be a technological world leader, it should stick to its word and demonstrate that it's a reliable partner.

ITER has come a long way since the November day in 1985 when the idea was first proposed by Soviet head of state Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President Ronald Reagan. Now, it might be all that stands in the way of an abundant supply of clean energy for the planet. America should place a little more faith in the kid in the corner.

The author's most recent Op-Ed was "Why the Supercomputing Arms Race Benefits Everyone." The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This article was originally published on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus