Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Most animals have a circadian clock that helps them distinguish night and day, but now researchers have found coastal animals seem to be equipped with a separate clock to track time via the tides.

The evidence comes from the discovery of internal clock genes that help some marine animals track the ebb and flow of the tides, according to two studies detailed today (Sept. 26) in the journals Current Biology and Cell Reports.

"The discovery of the circadian clock mechanisms in various terrestrial species from fungi to humans was a major breakthrough for biology," said Current Biology study co-author Charalambos Kyriacou of the University of Leicester, in a statement. "The identification of the tidal clock as a largely separate mechanism now presents us with an exciting new perspective on how coastal organisms define biological time."

Though the tidal clocks have only been found in two species so far, it's possible that multiple internal clocks could be widespread in sea-dwelling — and perhaps land-dwelling — creatures.

Internal clocks

For years, scientists thought the circadian clock guided the tidal behavior of marine animals. In almost all land-based animals, including humans, the circadian clock orchestrates rhythmic changes in physiology and behavior based on night and day.

But for animals at sea, life is guided by the ebb and flow of the tides, caused by the moon's gravitational pull on the Earth. For instance, a crustacean called Eurydice pulchra swims out in search of food with the incoming tides, then burrows in the sand once the tide departs. [6 Wild Ways the Moon Affects Animals]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To understand how animals keep track of this ocean rhythm, Kyriacou and his colleagues caught Eurydice pulchra off the coast of Wales every season, then identified their circadian clock genes. When they turned off those genes or disrupted the circadian cycle by exposing the creatures to bright light for several days, they found that cells linked to natural sunscreens were completely thrown off.

Yet like clockwork, the crustaceans still swam out every day on 12.4 hour cycles, suggesting the creatures had a separate internal clock anchored by the tides.

"This shows that the 12.4 hour clock is independent from the circadian clock. I expect tidal rhythms in many coastal organisms will follow this rule, including insects, crabs, even plants," Kyriacou said.

Multiple species

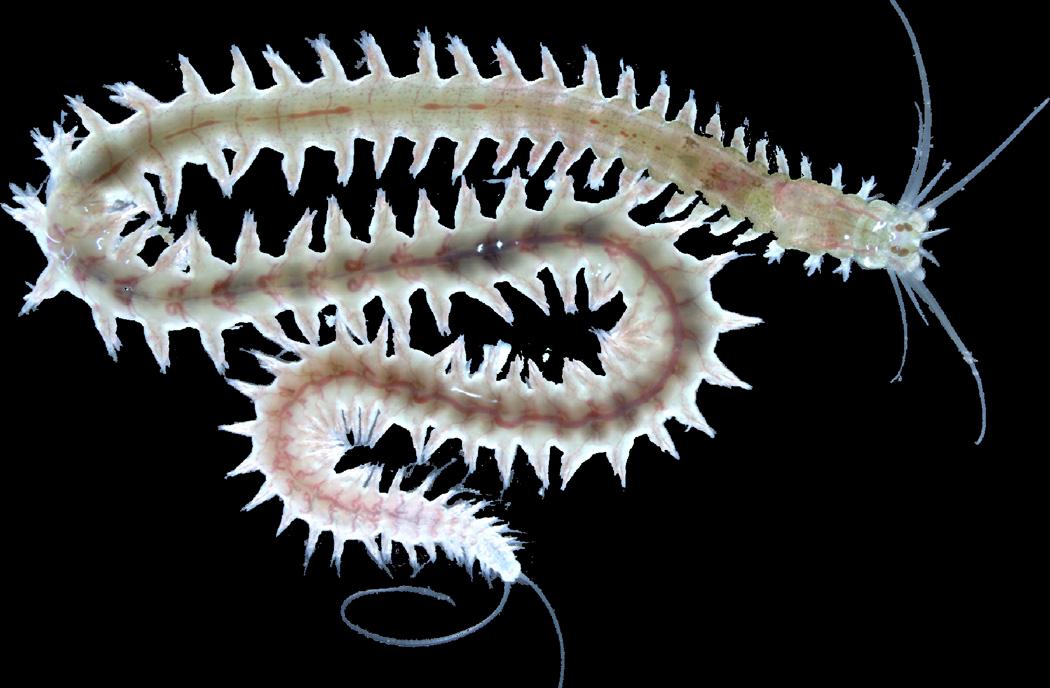

In another study, researchers took a look at marine bristle worms. Bristle worms sync their spawning seasons to the waning of the moon: Most mating happens under a new moon and almost disappears during full moons.

Yet when the researchers disrupted the bristle worms circadian clocks, their monthly lunar clock still ticked on. Their lunar clocks, however, seemed to affect the timing and power of circadian-based behaviors.

"Our results suggest that the bristle worm possesses independent, endogenous monthly and daily body clocks that interact," said Kristin Tessmar-Raible, co-author of the study detailed in Cell Reports and a researcher at the University of Vienna, in a statement. "Taking this together with previous and other recent reports, evidence accumulates that such a multiple-clock situation might be the rule rather than the exception in the animal kingdom."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus