Medieval Readers Had Eclectic Tastes

Nowadays, people bounce effortlessly from reading news to blogs to email. And it turns out the reading habits of people in medieval times weren't so different, a new book suggests.

People in 14th-century London consumed a variety of texts, often linked together in bound volumes. Arthur Bahr, a literature professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explores these habits in his new book "Fragments and Assemblages" (University of Chicago Press, 2013).

"Medieval manuscripts usually survive as fragments, and at the same time, they are also very often assemblages of multiple, disparate works," Bahr told MIT news. The interesting question is why these works were grouped together in that way, Bahr said.

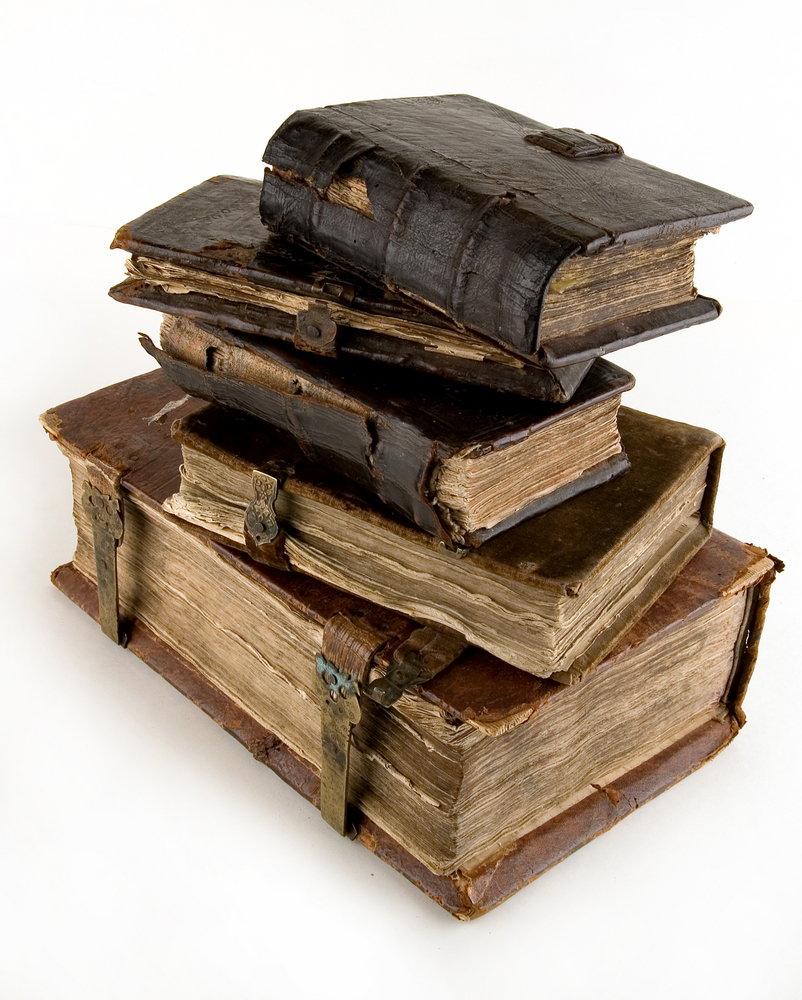

The printing press hadn't yet been invented, so people copied manuscripts by hand and bound them together, often including many different kinds of text in a single volume. [Image Gallery: Medieval Art Tells a Tale]

For example, the chamberlain for the city of London in the 1320s, Andrew Horn, possessed bound manuscripts that contained a mixture of legal treatises, French poetry and descriptions of London, among other things.

But Horn's bound manuscripts weren't just a random hodgepodge, Bahr said. Rather, Horn juxtaposed different texts to create "literary puzzles" for the reader. Placing poems next to legal documents portrayed law and literature as a kind of yin and yang, Bahr said.

The custom of cobbling together many different texts might explain the origin of Geoffrey Chaucer's "The Canterbury Tales," a linked set of stories that could be read in different orders. Chaucer arranged them in a loose sequence, but he also invited reader participation, Bahr said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Consider the "Miller's Tale," a somewhat crude comedy in "The Canterbury Tales" about a miller, his wife and her lover. In preparing to tell the story, Chaucer warns the reader that if they don't like dirty stories, they should skip to another section in the book. More than just a joke, the warning encourages readers to view the text in a new order. Skipping around in text may not seem new, but it is surprising, Bahr pointed out.

Medieval manuscripts also reveal the multilingual culture of 14th-century England, Bahr said. Chaucer wrote in English, but Latin was the language of the church and state, while French was the language of the upper classes. Welsh and other regional languages were also widely spoken.

Medieval scholars praise Bahr's book for unifying the divided time period and showing how the production of literature was an ongoing process.

The findings also reveal that today's sophisticated consumers of diverse global media may not be so different from consumers in the Middle Ages.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.