Could Life Exist On Jupiter's Icy Moon Europa?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Europa, Jupiter's icy moon, meets not one but two of the critical requirements for life, scientists say.

For decades, experts have known about the moon's vast underground ocean a possible home for living organisms and now a study shows that the ocean regularly receives influxes of the energy required for life via chaotic processes near the moon's surface.

Scientists discussed the implications of the new study, which appeared online Wednesday (Nov. 16) in the journal Nature, at an afternoon press briefing at NASA headquarters in Washington.

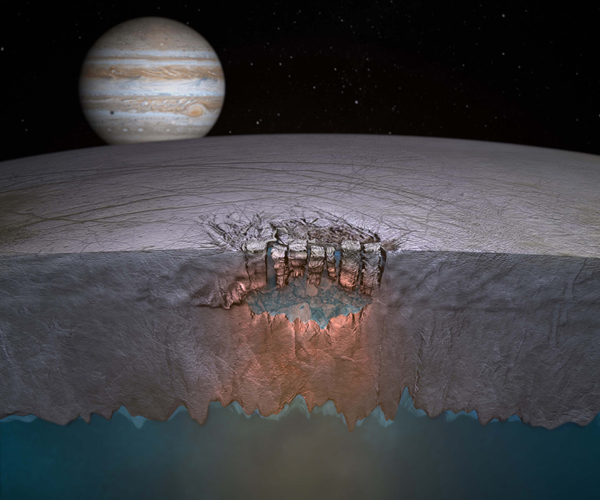

Lead author Britney Schmidt, a geophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin, explained that her team studied ice shelves and underground volcanoes on Earth in order to model the formation of odd features called "chaos terrains" that appear all over Europa. The researchers determined that it was heat rising from the moon's deep subterranean ocean and melting ice near the surface, creating briny lakes inside the moon's thick ice shell, that may have caused the collapse of these roughly circular structures above them.

These dynamic lakes, which melt and refreeze over the course of hundreds of thousands or millions of years, lie beneath as much as 50 percent of Europa's surface, the scientists said. [Jupiter Moon's Buried Lakes Evoke Antarctica]

Astrobiologist Tori Hoehler, a senior research scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., who was not involved in the new study, provided an outside perspective on its implications for life.

Europa's liquid water ocean "meets one of the critical requirements for life," Hoehler said, noting that its ocean chemistry is believed to be suitable for sustaining living things. "And what you're hearing about today from Britney bears on a second crucial requirement, and that is the requirement for energy."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The genesis of life on Earth is thought to have required some sort of injection of energy into the ocean perhaps from a lightning strike. And during the 3.8 billion years since then, life's existence has depended on the continuous influx of energy from the sun.

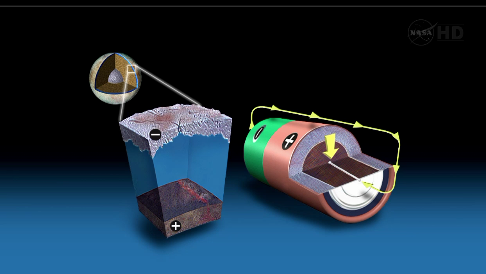

Cut off from the sun, Europa's subterranean ocean would need some other energy source to sustain life. Hoehler said spacecraft observations show that there is a huge amount of stored energy in Europa's mineral-rich crust, but it is separated from the liquid ocean below by at least 6 miles (10 km) of ice. Like the two terminals of a battery, energy can flow from the surface material to the ocean only if the two are somehow connected, he said.

"What you're hearing about here today would be a way to take this surface material, transport it potentially down into the ocean and in essence tap Europa's battery. When you tap that battery, you move from a system which checks one of the requirements for life to a system that checks a second critical requirement for life, and I think this really impacts the way we consider habitability on Europa."

Europan life isn't a done deal just yet, though. Water and energy aren't the only ingredients on the checklist for life , and scientists aren't sure whether Europa has the others, such as the necessary organic chemicals.

Louise Prockter, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md., said Europa's chaos regions "are going to be extremely important and possible future targets of exploration."

- Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter

- The Greatest Mysteries of Jupiter's Moons

- Will We Really Find Alien Life Within 20 Years?

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus