The Surprising Threat from Mexico's Awakened Volcano

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

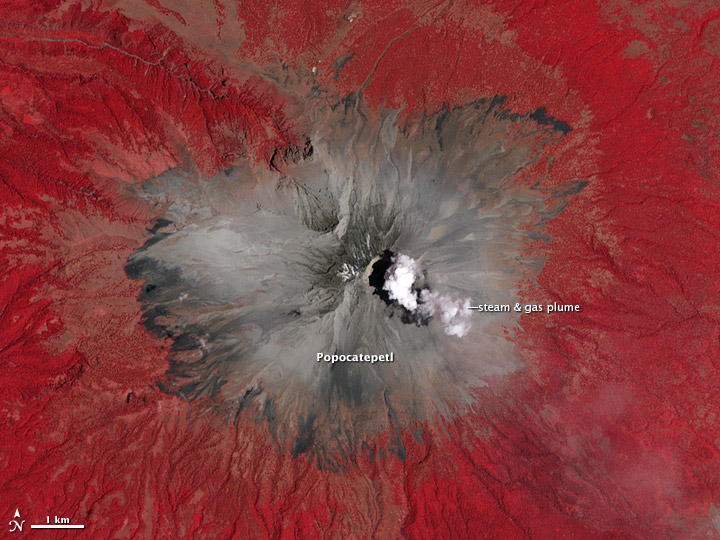

North America's second-tallest volcano recently rumbled to life, putting authorities on edge. Big eruptions of Mexico's massive Popocatépetl volcano are "few and far between," as one geologist says. Yet even without any dramatic fireworks, 17,800-foot (5,425-meter) "Popo" has the power to wreak havoc.

Geologist Mike Sheridan, a professor emeritus at the University at Buffalo, said that Popo and, in fact, many other volcanoes around the world harbor a means of destruction that many people may not associate with volcanoes: mudflows.

"And they don't even require an eruption, so they are less predictable," Sheridan told OurAmazingPlanet.

Popocatépetl lies about 40 miles (70 kilometers) southeast of Mexico City. The mountain reawakened in December 1994 after five decades of silence. Yet in the nearly 20 years since, the volcano has rarely exhibited the kind of vigorous activity that began the week of April 12.

Minor earthquakes have rocked the mountain, it has spewed out plumes of gas and ash, and multiple explosions have shot glowing rocks from the summit. [Images of Popocatépetl in action.]

The mountain has the potential to erupt magnificently once every 2,000 or 3,000 years. "It has big eruptions, but they are so few and far between," Sheridan said. "But they have been pretty big. So that is the scary part."

Hidden threat

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mudflows, also called debris flows and lahars (an Indonesian word), occur when water suddenly mixes with volcanic ash near a volcano's summit. The water can come from a multitude of sources — an explosive eruption that melts a mountaintop glacier, a sudden deluge of rain — with equally devastating results.

They are a big ongoing hazard, said Ben Andrews, a research geologist at the Smithsonian's Global Vulcanism Program.

"Thinking about them as mud is technically accurate, but conceptually it's more like a wall of cement flowing," he told OurAmazingPlanet, "and it destroys pretty much everything in its path."

As a flow rushes down a mountainside, it typically picks up large boulders and anything else that lies in its way.

Sheridan and colleagues mapped out possible scenarios for debris flows from snow-topped Popo the last time the mountain rumbled in its sleep, in 2000. They showed that flows could affect surrounding population centers.

Popocatépetl's current activity has triggered a few small debris flows, but it isn't likely to produce any large ones, Sheridan said. However, it has done so in the past.

In one large eruption about 11,000 years ago, Popocatépetl produced mudflows that inundated surrounding valleys, wiping out towns and villages, Sheridan said.

Both Sheridan and Andrews pointed to a 1985 eruption of Colombia's Nevado del Ruiz volcano to illustrate the insidious danger posed by debris flows.

"That eruption was fairly small," Andrews said. Yet it melted glaciers atop the mountain, producing a moving wall of debris that thundered down. The town of Armero — a full 45 miles (74 km) from Nevado del Ruiz — was essentially wiped away a full two hours after the eruption.

One girl's horrific case came to symbolize the tragedy. Thirteen-year-old Omayra Sanchez was buried up to her neck and hands in muck. For three days, volunteers struggled to free her as water slowly rose, but Sanchez died, held fast by the debris around her. In total, the 1985 mudflow killed more than 23,000 people.

A way out

Such tragedies are avoidable. "Mudflows can be detected and there can be a warning of up to a half-hour in advance," Sheridan said.

"It's definitely an escapable hazard if there's a warning," Andrews said. "These flows will knock down pretty much everything in their path, but they're restricted to valleys. And they're not moving at hundreds of miles per hour, they're moving at tens of miles per hour."

If warnings come in time and people move up to high ground, they can stay safe. The important thing is maintaining an accurate warning system so that people heed them, the scientists said.

"By the time you see it coming at you, it's probably too late," Andrews said.

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain. Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus