The Big Bailout: Product of a Flawed Democracy

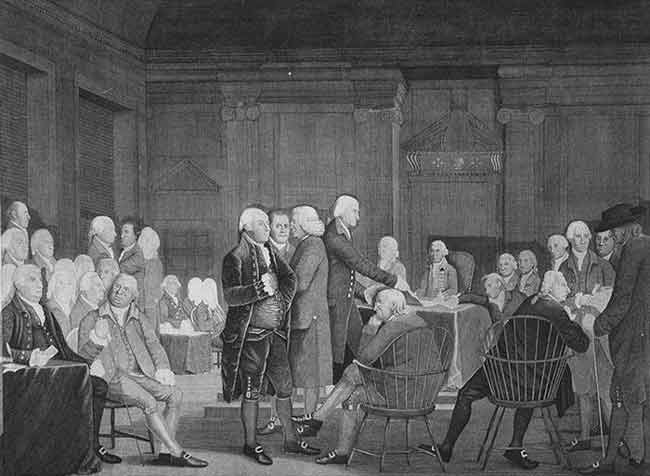

When the $700 billion emergency bailout of the struggling U.S. economy was finally passed by Congress on Oct. 3 after an arduous period of political wrangling, it was against the wishes of an overwhelming majority of the American public. Now, with more bailouts in the offing and Main Street still skeptical about handing so much cash to Wall Street (and now possibly Detroit), it's worth asking: How the heck did that happen? While economists, politicians and the public remain divided on whether giant bailouts ultimately help or harm the economy, many argue the act was simply an affront to American democracy. Is a government that ignores the sentiment of its people what the Founding Fathers had in mind? In a word, yes. Democracy in America was flawed, on purpose, from the beginning. Founding Fathers worried about us When George Washington, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson and other early leaders sat down to draft the documents that would define the new government of the United States, it never crossed their minds to create a purely democratic state, historians say. In many ways, the Founding Fathers believed that collectively we could be — for lack of more eloquent words — a gaggle of idiots. Pure democracy, born in ancient Greece, allows citizens to directly control a state’s decisions by having vote on each issue. In Athens, these votes were conducted among an assembly of 500 citizens not elected to the post but chosen by annual lottery. In addition to the obvious problems of operating a pure democracy in a large, populous territory like the United States, this ancient system was rejected outright because the Founding Fathers believed that the classic majority-rules tenet of democracy could actually become dangerous, allowing mobs of 50 percent plus one to force their will on minority groups. Two wolves and one sheep voting on who gets eaten for dinner does not a democracy make, they argued. Instead, the drafters of the constitution preferred a system where government was run in the people’s interests but not by proxy on each issue, making the legislative process much more convenient and speedier, if necessary. A representative democracy in the form of constitutional republic, with a set of individuals given the authority by the people to run the country on their behalf, was their compromise. Arguably, the system has worked ever since, with checks and balances put in place to prevent anyone from wielding too much power and to protect individual freedoms. It isn’t a pure democracy, but a functional one that, in theory, still lets the people make decisions. Unpopular decisions go way back Of course, in practice, that isn’t always the case. Congressmen and women don’t always vote according to the will of their constituents and people don’t necessarily trust them to. In a pure democracy, public opinion would have squashed the bailout — technically called the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act — quite easily. But it certainly isn’t the first unpopular bill approved by congress, nor will it be the last. The beginning of this millennium alone has seen several cases where Congress went against public opinion, the watchdog Patriot Act of 2001 and the Iraq Resolution of 2002 among them. It has happened earlier than that too. Several emergency bailouts in the 1970s of American industrial stalwarts such as Lockheed and Chrysler were unpopular but approved. Few were happy about the military draft bill passed in the 1940s and put to use during World War II and the Vietnam War, but that didn’t stop Congress either. Even Franklin D. Roosevelt’s sweeping New Deal reforms in the 1930s were denounced at first by the majority of the American people, who couldn’t stomach the thought of even more of their dwindling savings frittered away to taxes. The bailout then, as uncertain as its outcome remains, may be unpopular but is still a part of the democratic process as intended by the Founding Fathers, many experts argue. Ultimately it means that the government will sometimes get it wrong, tick people off and make decisions that don’t seem to make sense at the time. They will also get some things right. The Founders simply hoped that the latter would happen more often.

- Video – Finding George Washington: Truths Revealed

- Financial Fiasco: Can America Recover This Time?

- Recession Worries Help Fuel Recession

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.