Why Iceland Volcano's Eruption Caused So Much Trouble

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

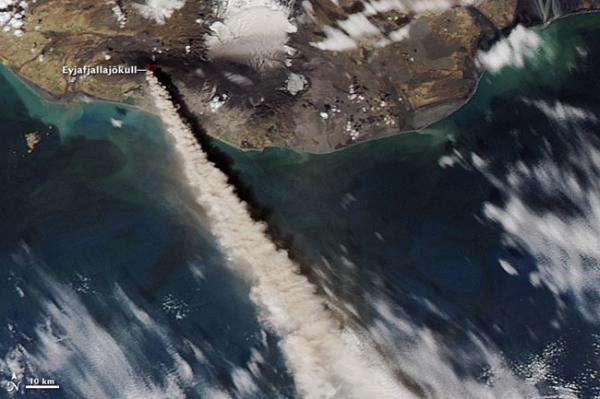

Jagged flecks of ash spewed into the air may have boosted the effects of the 2010 eruption of Iceland's Eyjafjallajökull volcano, which paralyzed flights across Europe, a new study finds.

The ash plume from Eyjafjallajökull caused turmoil in the air for nearly a month. Still, the eruption was a relatively small event. For instance, the plume never reached more than about 6 miles (10 kilometers) in height, and the volcano only spewed out about 9.5 billion cubic feet (270 million cubic meters) of ash over the course of several months, while some eruptions can spew out many times more than that in the span of a single day.

The reason that Eyjafjallajökull had such widespread influence was due to how the volcano's ash spread unusually far and stayed for an oddly long time in the atmosphere. To learn more about why this was, a group of scientists collected ash samples from across Iceland.

The researchers found that at Eyjafjallajökull's vent, upwelling magma violently reacted with nearby glacial water. This rapid cooling made the magma contract and fragment into fine, jagged motes of ash. Near the end of the eruption, equally fine, porous ash was generated when small gas bubbles trapped in the molten rock expanded as the magma neared the surface.

The investigators found that the median width of all the ash grains was less than 1 millimeter wide. Starting about 6 miles (10 km) from the vent and moving outward, particles smaller than 16 microns — about a sixth the width of a human hair — became more than 20 percent of the mix.

Computer models suggest the irregular shapes of these jagged and porous ash grains made them less aerodynamic, increasing how long they spent aloft. This helps explain why a small eruption still impacted a large area.

"This was not a big eruption, but still it caused problems over Europe and the Northern Atlantic," said researcher Piero Dellino, a volcanologist at the University of Bari in Italy. "This means that our complex society is not prepared to face natural hazards. We have to therefore learn from this lesson, considering that other volcanoes in Europe can produce much bigger eruptions — see, for example, historical events of Vesuvius." [10 Biggest Volcanic Eruptions in History]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dellino noted that their research took place well after the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, which might call their findings into question.

"At the moment, it is impossible to monitor in real-time the content and concentration of fine ash in the eruption cloud," he said. "We need to advance science and technology in order to get data as soon as possible after eruption initiation."

The scientists detailed their findings online Jan. 4 in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Solid Earth.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus