How Do Caves Form?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

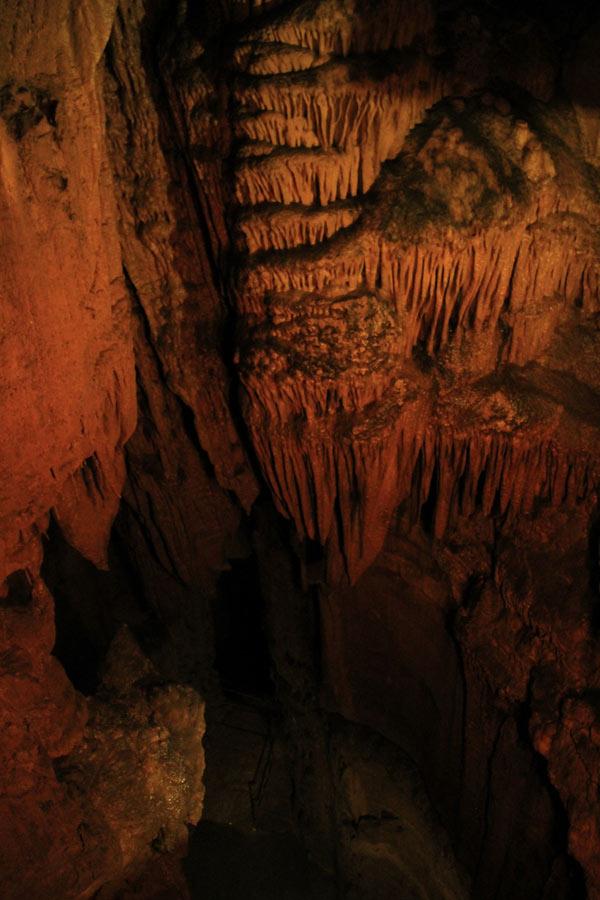

Caves can offer a thrilling glimpse into a hidden universe of extremes, one cut off from the rules of the outside world.

Eyeless creatures slither in utter darkness, crystals grow to the size of dump trucks , and sulfuric acid burbles up from deep inside the Earth.

But for all their exoticism, caves are formed from just two commonplace ingredients: rock and water.

Acidic rock-eater

Not just any rock will do generally caves are formed from gypsum, limestone, dolomite or even salt.

"You need a rock type that can dissolve in water," said Randall Orndorff, a geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

When rainwater is introduced to this kind of rock, either seeping in through tiny pores in the rock surface, or, more typically, dribbling in through larger cracks, the rock will begin to dissolve. That's because rainwater is slightly acidic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Raindrops pick up acidity from chemicals in the atmosphere as they hurtle earthward; although the atmosphere's chemical composition varies, generally rain water has a pH of around 5, roughly the same as black coffee. (The pH scale measures the acidity or alkalinity of a liquid and runs from 0 to 14, with 0 the most acidic and 14 the most basic. Pure water has a pH of 7, considered neutral.)

But rock and rainwater don't quite cut it; there's one more catalyst that plays an important role in cave formation: plants.

Orndorff said that wetter regions on the planet also tend to have denser vegetation, which means thick mats of organic material accumulate. Plants die and decompose in a process that produces carbon.

"So rainwater, when it hits, starts percolating through the soil," Orndorff said, "and as it does it starts picking up all that carbon in the decaying organic material. The rainwater itself turns into carbonic acid."

That carbonic acid slowly eats through the rock.

Tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of years later, behold! A cave.

Mother Nature's aqueduct

Precisely what kind of cave you'll end up with is partly determined by gravity.

Water wants to go down. Just as rivers on the Earth's surface flow toward the sea, Orndorff said, caves are pipelines for water to move from one place to another.

If the water takes a fairly direct route, you can end up with what are called pit caves vertical shafts stretching straight down into the rock.

If the water takes a more circuitous route, you get a horizontal cave system. Mammoth Cave, in Kentucky, a horizontal cave, is the longest cave system in the world , stretching for at least 390 miles (627 kilometers) beneath the surface of the Earth.

However, some caves turn this tidy formula on its head and form from the bottom up. Water trapped in aquifers deep inside the Earth sometimes comes into contact with sulfide-loaded rocks, like pyrite, Orndorff said. This creates sulfuric acid, which, with enough hydraulic pressure, can push up through the rock to carve out a cave.

Although caves prove irresistible destinations for timid and intrepid explorers all over the world, Orndorff said there are probably many caves humans haven't found yet, "because you'd need scuba gear to get to them."

When it comes to caves, Orndorff said, "we're probably only scratching the surface."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus