Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

As the sun dips below the horizon and the light starts to dim, lucky observers may spot a rare, brief flash of emerald. This is the "green flash," which can sometimes be seen right after sunset or before sunrise.

So what causes the green flash?

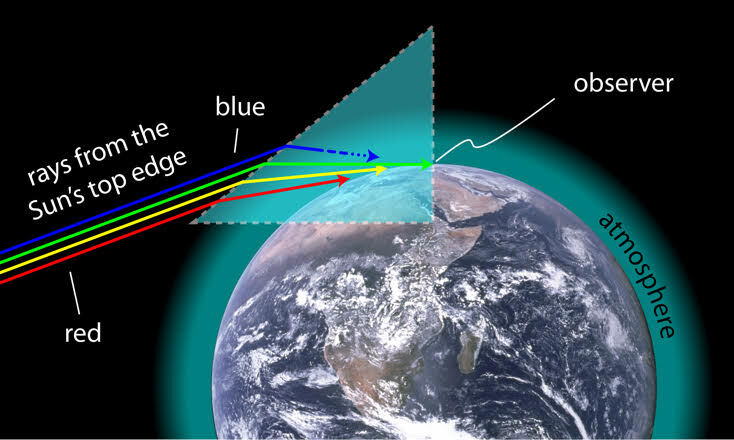

Like many colorful spectacles in the sky, such as rainbows, the green flash is the result of sunlight being separated into different colors. Normally, sunlight is white because it is made up of all of the wavelengths of visible light, Johannes Courtial, an optics researcher at the University of Glasgow, told Live Science. But when white light passes through a medium that is higher-density, like glass or water, at an angle, wavelengths of different colors start to bend and separate. This separation is called refraction.

Article continues belowEarth's atmosphere, with its varying density of gases, can refract light, too. It's why we sometimes see rainbow halos around the sun, or mirages in the distance, said Jan Null, a meteorologist based in California. Refraction is especially apparent when the sun gets closer to the horizon, because sunlight is entering the thickest part of the atmosphere at a particularly sharp angle. This is when the green flash may be visible, Null said.

Most green flashes fall into two categories. One type occurs just before the sun disappears. This is the one referenced in Jules Verne's novel "The Green Ray," Null said. But the type Null sees more often is when the sun is still above the water. "You get this light off the top of the disk," he said.

Related: When will the sun explode?

How to see the green flash

For the best chances of seeing this verdant flash, the right conditions need to align. First, you have to be able to see the sun while it's close to the horizon, like on the coast or high up in the mountains, Courtial said. In coastal areas like San Francisco, you're also most likely to spot the green flash on warmer days, when there's a layer of warm air on top of colder water, Null said. These layers of air help to refract sunlight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Whether green is visible also "depends on what stuff there is in the atmosphere," Courtial said. Particles can scatter blue and purple light, making green light more apparent. Courtial demonstrated this in a simple experiment: by adding milk powder to a tank full of water and then shining a white bike light into it. When he added just the right concentration of those particles, "you see a vibrant green," he said.

Of course, you also need to be able to have a direct line of sight of the sun on a clear day to see the green flash, which is easier said than done. (Never look directly at the sun without special eye protection, as it can damage your eyes.) So Null recommended using a camera with a zoom lens to capture the green flash (again, make sure to exercise caution and protect your eyes). Zooming in on the sun also makes tiny flashes more visible, Null noted.

Green flashes usually happen in less than a second. But if you're lucky, a green flash could shine for a minute or two. Null has observed this only rarely, even after over 45 years of documenting this phenomenon. Green flashes can be sustained if the conditions in the atmosphere stay stable enough, he said.

"It's really weird when you see green in the sky," Courtial said, which is likely why the green flash is so intriguing. So, the next time you're watching a sunset, indulge in that fascination. Now, you know more on how it happens.

Alice Sun is a science journalist based in Brooklyn. She covers a wide range of topics, including ecology, neuroscience, social science and technology. Her work has appeared in Audubon, Sierra, Inverse and more. For her bachelor's degree, she studied environmental biology at McGill University in Canada. She also has a master's degree in science, health and environmental reporting from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus