'Peaceful' Minoans Surprisingly Warlike

The civilization made famous by the myth of the Minotaur was as warlike as their bull-headed mascot, new research suggests.

The ancient people of Crete, also known as Minoan, were once thought to be a bunch of peaceniks. That view has become more complex in recent years, but now University of Sheffield archaeologist Barry Molloy says that war wasn't just a part of Minoan society — it was a defining part.

"Ideologies of war are shown to have permeated religion, art, industry, politics and trade, and the social practices surrounding martial traditions were demonstrably a structural part of how this society evolved and how they saw themselves," Molloy said in a statement.

The ancient Minoans

Crete is the largest Greek isle and the site of thousands of years of civilization, including the Minoans, who dominated during the Bronze Age, between about 2700 B.C. and 1420 B.C. They may have met their downfall with a powerful explosion of the Thera volcano, which based on geological evidence seems to have occurred around this time.

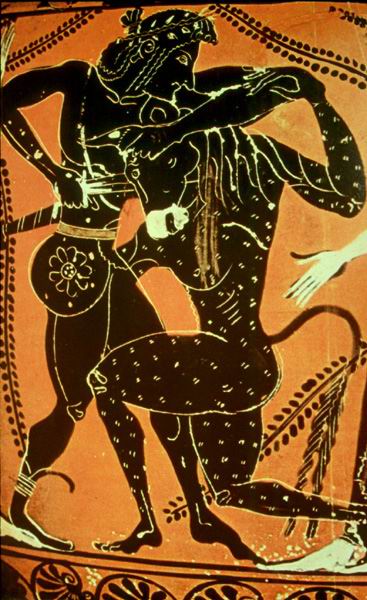

The Minoans are perhaps most famous for the myth of the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull that lived in the center of a labyrinth on the island. [10 Beasts & Dragons: How Reality Made Myth]

Minoan artifacts were first excavated more than a century ago, Molloy said, and archaeologists painted a picture of a peaceful civilization where war played little to no role. Molloy doubted these tales; Crete was home to a complex society that traded with major powers such as Egypt, he said. It seemed unlikely they could reach such heights entirely cooperatively, he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"As I looked for evidence for violence, warriors or war, it quickly became obvious that it could be found in a surprisingly wide range of places," Molloy said.

War or peace?

For example, weapons such as daggers and swords show up in Minoan sanctuaries, graves and residences, Molloy reported in November in The Annual of the British School at Athens. Combat sports were popular for men, including boxing, hunting, archery and bull-leaping, which is exactly what it sounds like.

Hunting scenes often featured shields and helmets, Molloy found, garb more suited to a warrior's identity than to a hunter's. Preserved seals and stone vessels show daggers, spears and swordsmen. Images of double-headed axes and boar's tusk helmets are also common in Cretian art, Molloy reported.

Even the yet-undeciphered language of Minoan may hint at a violent undercurrent. The hieroglyphs include bows, arrows, spears and daggers, Molloy wrote. As the script is untranslated, these hieroglyphs may not represent literal spears, daggers and weapons, he said, but their existence reveals that weaponry was key to Minoan civilization.

"There were few spheres of interaction in Crete that did not have a martial component," Molloy said.

Some of the violent nature of Minoan society might have been missed because archaeologists find few fortified walls on the island, Molloy wrote. It may be that the island's rugged topography provided its own defense, he said, leaving little archaeological evidence of battles behind.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.