Humans Might Sense Oxygen Through Skin

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A breathtaking trick potentially left over from our amphibian ancestors might be found in us — the ability to sense oxygen through our skin.

Amphibians have long been known to be capable of breathing through their slimy hides. In fact, the first known lungless frog that breathes only through its skin was discovered recently in the rivers of Borneo.

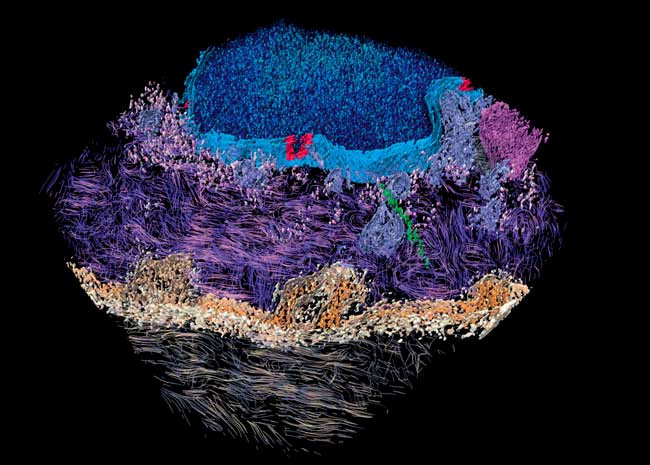

Now the same oxygen sensors found in frog skins and in mammalian lungs have unexpectedly been discovered in the skin of mice.

"No one had ever looked," explained researcher Randall Johnson, a molecular biologist at the University of California, San Diego.

Mice and frogs are quite distant relatives, separated by more than 350 million years of evolution, so the fact they have these molecules in common in their skin suggests these compounds might well be found in the skin of other mammals also, such as humans.

"We have no reason to think that they are not in the skin of people too," Johnson said.

The discovery could lead to ways to boost oxygen levels in the blood of athletes in peak health and also people in bad health.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These molecules not only detect oxygen, but one of the compounds the researchers investigated helps ramp up levels of vital red blood cells, which ferry oxygen around the body.

When oxygen is limited, the body hikes up red blood cell production by pumping out the hormone erythropoietin, or "epo." Normal mice breathing in air that is 10 percent oxygen — a dangerously low level akin to conditions at the top of Mount Everest, and roughly half that of air at sea level — boost epo levels up 30-fold. However, mice that had the oxygen sensor HIF-1a genetically removed from their skin failed to produce this hormone even after hours of such low oxygen.

These findings, if they hold true in humans, suggest one could jack up the level of oxygen circulating inside the body simply by manipulating the skin and boosting red blood cell levels. This could help treat lung diseases and disorders such as anemia without injecting drugs that mimic epo, which make up a multibillion-dollar market, Johnson said.

Elite athletes also often try ramping up how much oxygen gets delivered to their muscles in order to improve their performance. They often do this by training at high altitudes or in low-oxygen tents. The new study suggests they might want to expose their skin as well as breathing in low-oxygen air to enhance their performance. "It's hard to say what exactly might be done, however — there's a lot we don't know yet," Johnson explained.

One important future goal for scientists is to investigate different kinds of mammals for this response. "Clearly, aquatic mammals would differ greatly in how their skin adapts to oxygen, and in all likelihood high altitude animals from those adapted to life at sea level," Johnson said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the April 18 issue of the journal Cell.

- Incredible Animal Abilities

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About Animals

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus