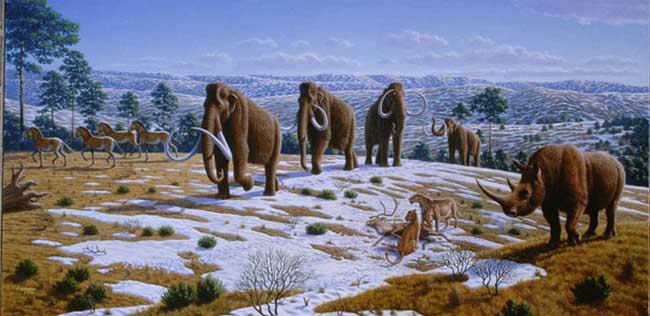

Study: Humans Drove Final Nail into Mammoth Coffin

Humans may have struck the final blow that killed the woolly-mammoth, but climate change seems to have played a major part in setting up the end-game, according to a new study.

Though mammoth populations declined severely around 12,000 years ago, they didn't completely disappear until around 3,600 years ago. Scientists have long debated what finally drove the furry beasts over the edge. Researchers led by David Nogues-Bravo of the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Spain used models of the climate, as well as models of woolly-mammoth and human populations, to study the relative importance of various factors leading to the mammals' demise.

The scientists published their results in the journal PLoS Biology.

The team found that the brunt of the damage done to mammoths was due to Earth's warming weather around 8,000 to 6,000 years ago. Since Earth was coming out of a glacial period at that time, temperatures were climbing and recasting the planet's landscape, and the mammoth's preferred habitat, steppe tundra, was vastly reduced.

The researchers calculated the temperature window in which mammoths can survive by matching known fossil specimens with climate models. They determined the temperature at the time each mammoth specimen lived and combined the data to get an overall picture of the animals' preferred climate range.

The team found that by 6,000 years ago, mammoths were relegated to 10 percent of the habitat that had previously been available to them 42,000 years ago when the glaciers were at their largest size and greatest extent.

But climate doesn't seem to explain the entirety of the mammoth's extinction. These hardy animals had survived, barely, a previous interglacial period of planet warming around 126,000 years ago. Scientists have found some fossil bones from this time, so climate change didn't completely knock out mammoths then.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One difference between that first interglacial period and the second one during which they actually died off was the presence of humans. Around 6,000 years ago when the climate warmed in North Eurasia where mammoths lived, our ancestors were able to move in to the region. Once there, they might have hunted the already weakened population of mammoths to oblivion.

"During the [earlier] interglacial period, climates were fairly warm, so why didn’t [mammoths] go extinct then?" said Persaram Batra, a climate modeler at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, who worked on the study. "It could be because humans weren’t there. Mammoth populations were so sparse, that if there had been humans, maybe they would have gone extinct."

The researchers calculated that by 6,000 years ago, an optimistic estimate of mammoth numbers would mean humans would only have to kill one mammoth each, every three years, to push the species over the brink. A more pessimistic calculation figures that even if one mammoth per human were killed every 200 years, they would still die off.

"This paper argues that climate change would have reduced the size of the habitat for the mammoths to the point where hunting could have extinguished them," Batra told LiveScience. "We're arguing that it's sort of a combination. Climate change probably didn't do it completely, but it made their life so precarious that humans could come in and kill them off."

- Image Gallery: The World's Biggest Beasts

- Scientists Aim to Revive the Woolly Mammoth

- Surviving Extinction: Where Woolly Mammoths Endured