Protective Skin Microbes Help Fight Off Disease

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

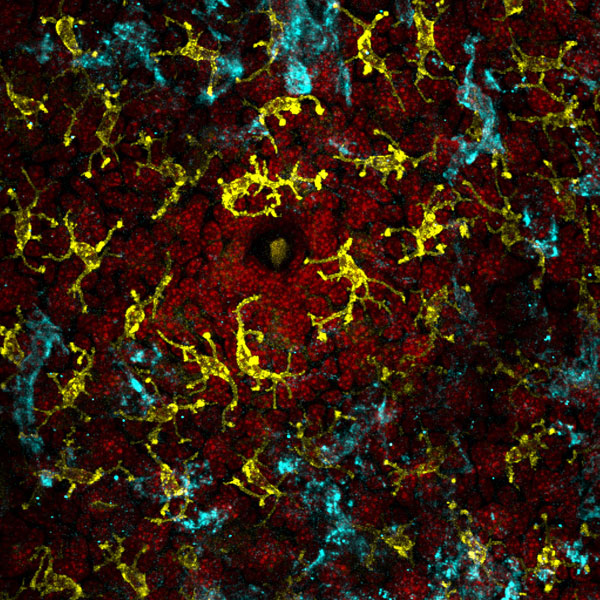

A massive number of microbes live in our guts, on our skin and elsewhere, all over our bodies. And these tiny companions aren't freeloaders — in fact, at least some of them may help keep us healthy, increasing evidence indicates.

The newest research focuses on the microbes living on skin, and finds that these bugs may help stimulate the body's defenses.

"The skin, in the absence of microbes, is not capable to fend for itself. It requires commensals [these beneficial microbes] to promote immunity against infection," researcher Yasmine Belkaid, who studies the immunology of infectious disease at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told LiveScience.

The microbes appear to prime immune cells called T-cells, preparing them to protect the body, Belkaid said. She and others have documented a similar phenomenon in the gut, where certain resident microbes can stimulate T cells. The mechanics of this process in the gut, however, are different, Belkaid said. [Gallery: Belly Button Bacteria]

For this study, researchers led by Shruti Naik, a graduate student in Belkaid's lab, gave skin-infecting parasites to mice with healthy populations of skin microbes and to mice that lacked skin microbes.

They found the normal mice developed more pronounced lesions than the mice that lacked the microbes. While this may sound counterintuitive, the inflamed lesions were caused by the immune response, not the parasites themselves, so these sores were actually good signs for the mice.

The researchers also added a single species of skin microbe common in humans and mice, Staphylococcus epidermis, to some of the microbe-free mice. This microbe by itself enabled the mice to mount an immune response on par with the mice that had healthy, diverse skin microbe populations.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Their research showed that commensal microbes, such as S. epidermis and possibly others, stimulate skin and immune cells in it to produce a substance called Interleukin-1, which activates T cells. T cells regulate the inflammation associated with an immune response to invading cells. As a result, the T cells become more responsive to invading cells, like the parasites used in the experiment.

It’s not yet clear how these microbes promote the production of Interleukin-1, Belkaid said.

Similar relationships may exist for microbes living elsewhere on the human body, such as the lungs.

"I think it will be fascinating to start exploring other tissues," she said. "Even the skin is not one single kind of tissue."

Discoveries such as this one imply that some disorders may be related to inadequate microbe populations on the skin, and they may lead to the development of treatments that can help stimulate the body's immune response, she said.

The research is detailed in Friday's (July 27) issue of the journal Science.

Follow LiveScience writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_ParryorLiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus