Storytelling and Narrative in Science

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This ScienceLives article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

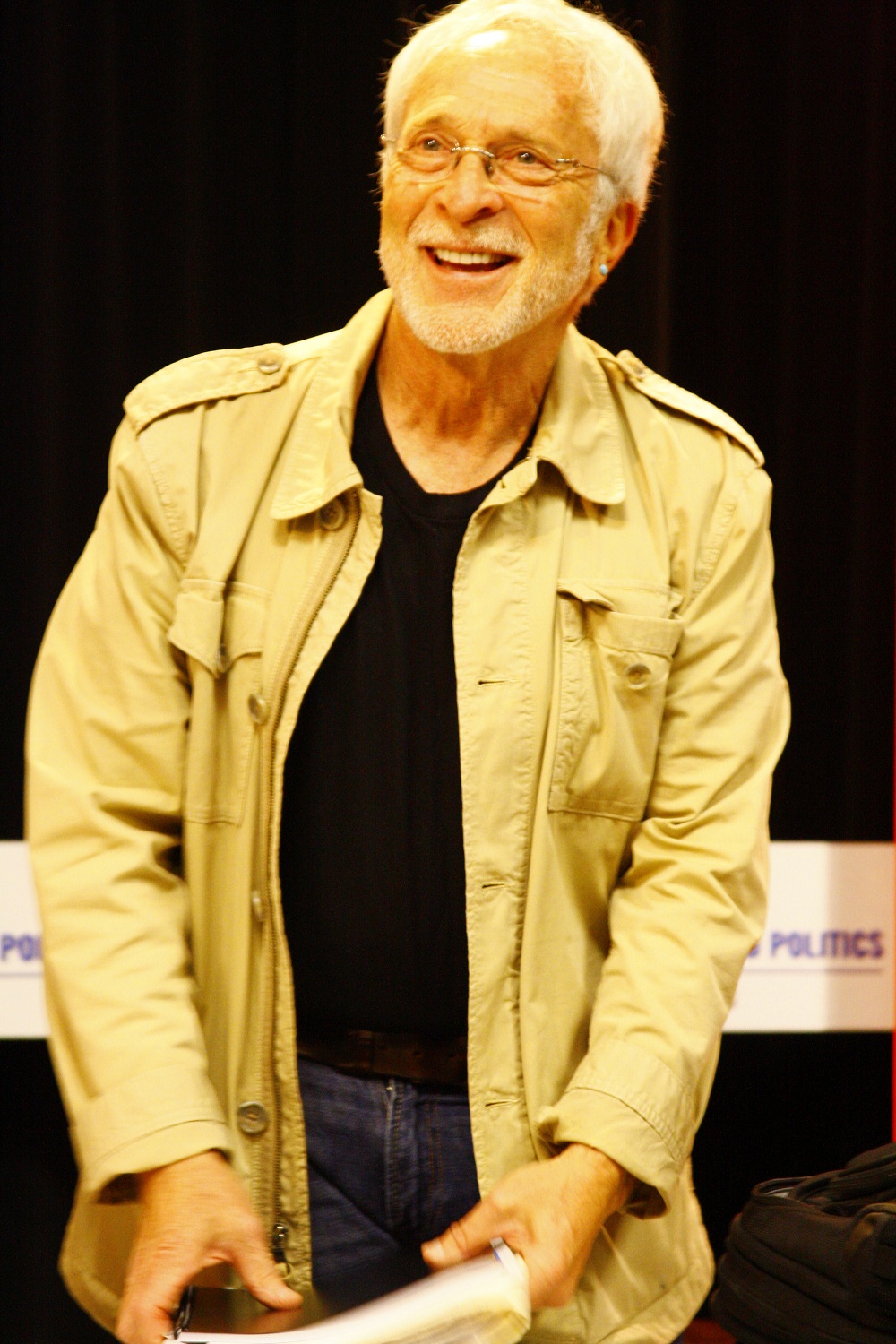

Lee Gutkind, dubbed by Vanity Fair as "the Godfather behind creative nonfiction," is the author and editor of more than 20 books, including the award-winning "Many Sleepless Nights" (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990), a chronicle of the breakthroughs in the organ-transplant world.

Gutkind is founder and editor of Creative Nonfiction, the first and largest literary magazine to publish nonfiction exclusively, and Distinguished Writer-in-Residence in the Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes at Arizona State University. Gutkind has lectured to audiences around the world — from China to the Czech Republic, from Australia to Africa.

His topics include robots, healthcare and the worldwide storytelling explosion. The need for a personal and public narrative begins in literature and extends to advertising, business, politics, law and science. Creative nonfiction, Gutkind said, is a movement — not a moment.

Gutkind's latest anthology is "Becoming a Doctor: From Student to Specialist, Doctor-Writers Share Their Experiences" (W. W. Norton & Company, 2010). Gutkind has been supported by National Science Foundation in efforts to bridge science communicators with science and technology policy leaders to ensure that the public is better informed about major issues of science and innovation policy.

Below, he answers the ScienceLives 10 Questions.

Name: Lee Gutkind Institution: Arizona State University Field of Study: Writer and Editor, Creative nonfiction

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What inspired you to choose this field of study? I am a writer and editor with a passion for true storytelling. To me, science matters, research matters and knowledge matters, whatever the field. I discovered early on that lots of people want to learn — they aren't adverse to insight and education — but that the people who had the background, experience and knowledge to teach them were too busy talking to one another and did not know how to talk to the rest of the world.

I discovered that I, a writer of what is known as creative nonfiction, could do the research and bridge the gap in my books and lectures through true storytelling. This is not "dumbing down" or writing for eighth graders. It is writing for readers across cultures, age barriers, social and political landscapes.

What is the best piece of advice you ever received? From Winston Churchill: "Never give in, never give up. Never. Never. Never. Ever."

And from a patient recuperating from a suicide attempt that I met while writing about the dynamics behind the scenes in a psychiatric hospital: "Fall down nine times — get up ten."

This is very relevant in research and in writing and telling true stories. The challenge is daunting. It is easy to make stuff up — and easy to dig up information and repeat it or report it to others. But to find a real life story with real people in real life situations is quite difficult and time-consuming. Yet, the rewards are worth the effort. People who receive information in true stories remember more, remember longer and are sometimes more easily persuaded.

What was your first scientific experiment as a child? As a child I had no interest in science whatsoever — then I started writing and recognized how relevant it was. My first book about science and medicine captured the world of organ transplantation in 1989 from the points of view of all of the participants — scientists, surgeons, social workers, organ recipients and even donor families.

In "Many Sleepless Nights," I tried to live the lives of all of the actors in the transplant community; I jetted through the night on organ donor procurements, and scrubbed with surgeons. I lived the life. I was turned on to science and medicine and the impact it could make, but I was perplexed by the information gap — the annoying and illogical gulf between the scientists and the real world — the people who would ultimately benefit from the science.

Once I realized I could bridge that gap through creative nonfiction and true storytelling, I was hooked. I've since written about robotics, pediatrics and personalized medicine, hopefully opening the pathways of understanding to clarify mysteries and connect constituencies.

What is your favorite thing about being a researcher? I work like an anthropologist, immersing myself in other people's worlds. This is wonderful work because I become deeply involved so that I can see and appreciate these worlds through other people's eyes, and I learn to understand how researchers think — what motivates and challenges them, why they laugh and sometimes cry.

Then through storytelling, I translate the knowledge and the personalities and weave a three dimensional portrait — to the real world. And just to clarify, I am true to fact; in creative nonfiction and true storytelling, as the title of my upcoming book proclaims, "You can't make this stuff up."

[Editor's note: The book is titled "You Can't Make This Stuff Up: The Complete Guide to Writing Creative Nonfiction — from Memoir to Literary Journalism and Everything in Between," (Da Capo Lifelong Books, coming in 2012)]

What is the most important characteristic a researcher must demonstrate in order to be an effective researcher? Persistence and faith in their abilities and dedication — go back to Churchill and the patient I met, referred to in the question above. Never give up.

What are the societal benefits of your research? My work becomes the vital connection between the scientist and engineer and the world they are trying to change — from consumers to legislators and beyond. Helping these groups understand each other will inevitably enhance the scientist's work and the consumers' support of science.

Who has had the most influence on your thinking as a researcher? My work has been influenced mostly by writers who pioneered the nonfiction storytelling form, creative nonfiction, including John McPhee, Ernest Hemingway, George Orwell and Gay Talese. I have also admired the writers Jack Kerouac, Phillip Roth, Joseph Heller and James Baldwin.

What about your field or being a researcher do you think would surprise people the most I have no background as a scientist whatsoever. In fact, I did not expect to graduate. I applied to five colleges and was accepted to none of them. I went into the military instead — and that experience changed my life.

If you could only rescue one thing from your burning office or lab, what would it be? After contemplating this question for a while, I have decided to equip my office with a first rate fire extinguisher.

What music do you play most often in your lab or car? Exclusively rock and roll — but every time my son and I take a car trip, which we do quite frequently and have for many years, we begin the journey by playing the Grateful Dead's "Truckin'" song at least twice.

Editor's Note: The researchers depicted in ScienceLives articles have been supported by the National Science Foundation, the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Science Lives archive.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus