Google Earth Update Erases Underwater 'Atlantis' Error

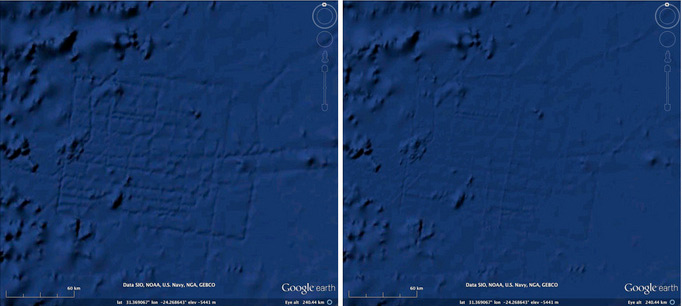

A Google Earth map that raised rumors of the lost city of Atlantis has gotten a much-needed update, ridding the seafloor of a gridlike pattern that some vigilant users suspected were sunken streets from the mythological underwater city.

In fact, Google Ocean, an extension of map program Google Earth, was merely displaying a data artifact from the sonar method that oceanographers use to map the seafloor. This week, Google updated the application with new seafloor data from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other groups.

"The original version of Google Ocean was a newly developed prototype map that had high resolution but also contained thousands of blunders related to the original archived ship data," David Sandwell, a Scripps geophysicist, said in a statement. "UCSD undergraduate students spent the past three years identifying and correcting the blunders."

The students also incorporated new data into the archive that Google uses to create its map of underwater topography. Researchers create this data by using sonar, or sound waves, that bounce off the seafloor and return information about its shape, not unlike how a bat uses sonar to "see" bugs. When Google uses lots of these surveys together, they sometimes overlap, creating strange gridlike patterns.

That's what happened in 2009, shortly after the launch of the extension. Eagle-eyed Google Ocean explorers spotted a large grid on the seafloor that looked strikingly like the streets of a well-organized small town. Immediately, "Atlantis" rumors started flying. [Fact or Fantasy? 20 Imaginary Worlds]

In fact, the grid was merely caused by overlapping datasets, according to NOAA. Besides that, the grid that looked like a little town actually covered an area of ocean more than 100 miles (161 kilometers) wide — not exactly small-town proportions.

The updated Google Ocean has been scrubbed of this Atlantis artifact. Google Ocean is also becoming increasingly accurate in other ways. The program now has 15 percent of its seafloor image taken from shipboard soundings at a 0.6-mile (1 km) resolution. Previous versions took only 10 percent of seafloor imaging from sonar soundings and the rest from extrapolations by scientists using satellite data.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even those estimates will soon be stronger: The next major upgrade is planned for later this year, and will use a new calculation technique that returns depth predictions that are twice as accurate as before.

"The Google map now matches the map used in the research community, which makes the Google Earth program much more useful as a tool for planning cruises to uncharted areas," Sandwell said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.