Experimental Monkey Vaccine Boosts Hopes in AIDS Fight

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

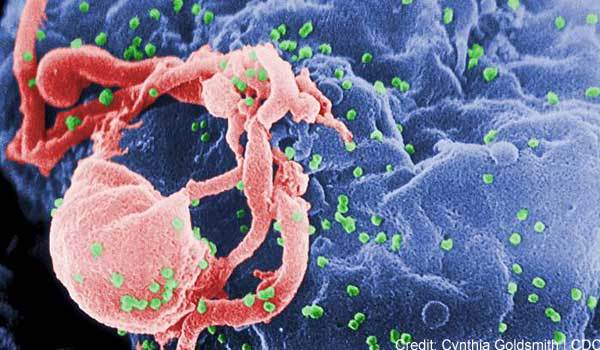

A new vaccine partially protects monkeys from an infection similar to HIV, according to a recent study.

Researchers looked at 40 rhesus monkeys exposed to the Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), a virus closely related to HIV.

Monkeys who received the experimental vaccine were 80 to 83 percent less likely to get infected each time they were exposed to SIV, compared with those who were given the placebo vaccine.

The experimental vaccine was engineered to trigger the monkeys' immune systems to fight the virus. Researchers often study the effects of an SIV vaccine in monkeys as a way to understand how to develop an HIV vaccine in humans.

This is an important step toward an HIV vaccine, said Dr. Adam Spivak, an HIV researcher at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

"This study demonstrates that the immune system can be prepared to respond to, and partially control, viral infection that mimics HIV-1 transmission in humans," Spivak said. HIV-1 is the type of the virus that causes most infections in people.

The study was published Jan. 4 in the journal Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Protected against viral infection

At the start of the study, 40 monkeys were injected with either the experimental vaccine or the placebo vaccine, and then given a booster shot at six months. Monkeys were then exposed to SIV six times, via intra-rectal administration of the virus, six months later.

After the virus was administered the first time, about 75 percent of monkeys that received the placebo vaccine became infected, whereas of those given the experimental vaccine, only 12 to 25 percent (depending on the particular shot they received) developed infections.

After the virus was given a third time, about half the animals that received the experimental vaccine were infected.

By the sixth administration of the virus, almost of the animals in the study were infected.

Still, the researchers also found that those given the experimental vaccine had a lower amount of virus in their blood than those given the placebo.

"This demonstrates that the vaccine provided some resistance to primary infection," Spivak said.

Results also showed that one vaccine ingredient — a protein called Env, which is involved with binding the virus with a cell — was key in helping to block the virus from entering the monkey's cells.

Next steps in HIV research

Although efforts have been made in previous studies, including the 2009 Thailand study that found one vaccine reduced the risk of contracting HIV by nearly a third, other recent trials of vaccines have not been as successful.

"There have been a number of human trials using a similar vaccine that have not worked, or there wasn’t enough evidence to show if the vaccine primed the immune system appropriately," Spivak said.

But he said the new study’s findings will provide a template for vaccine design and for measuring vaccine effectiveness for future studies.

"Researchers have shown that a vaccine can create an immune response,” he said. "That, in itself, is exciting."

Pass it on: New promise for a future human HIV vaccine comes from a recent study where researchers developed a vaccine that could prevent a similar infection in monkeys.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily on Twitter @MyHealth_MHND. Find us on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus