The Truth About Lie Detectors

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Washington is a city of lies, so perhaps it is no surprise that those in the nation's capital wishing to expose the truth have been fooled by lies about a polygraph's usefulness.

According to White House spokesman Tony Snow, earlier this month, the

White House will consider administering a polygraph to Clinton-era National Security Adviser Sandy Berger, who pleaded guilty to lifting documents from the National Archives in 2002 and 2003. Some say the documents, now nowhere to be found, might point to failures of the Clinton administration to uncover the 9/11 terrorist plot.

Politics aside (it was 18 Republican congressmen who wrote to Attorney General Alberto Gonzales in January requesting that Berger take a polygraph, but that was before allegations of certain falsehoods on Gonzales' part made the request a little awkward), the polygraph is no way to get to the truth.

Good liars

Good liars have little to lose and everything to gain from taking a "lie detector" test. It's the truthful people who need to worry about polygraphs.

A polygraph not a lie detector; it never was. A polygraph detects physiological expressions associated with lying in some people, such as a racing heart and sweaty fingers. The determination of truth vs. falsehood is a subjective interpretation by the polygraph examiner.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Not surprisingly, the examiner is often wrong. The anxiety associated with "oh no, they will detect that I'm lying" is rather similar to "oh no, they're going to think I'm lying when I'm not."

The polygraph is essentially a four-tier medical device that closely monitors respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure and electrodermal response, which is a method to detect minute changes in perspiration, usually from the fingertips. The machine is a marvel; its accuracy in detecting these physiological changes is not in question.

At the bequest of the U.S. government, the National Academy of Sciences (an organization of some of the smartest scientists in America, no lie) conducted an extensive study of the polygraph in 2002 and concluded "polygraph tests can discriminate lying from truth telling at rates well above chance, though well below perfection."

The Academy said the polygraph "rests on weak scientific underpinnings despite nearly a century of study." The high incidence of false positives—a truthful response determined erroneously to be a lie—makes the polygraph useless, the Academy said.

Just how bad?

The Academy researchers even provided a pertinent example for the Feds. Given the modern polygraph's strengths, the machine could uncover 8 out of 10 spies working at, say, a national atomic laboratory with 10,000 hypothetical employees. Sounds good, but the detection comes at the price of finding 1,600 innocent employees guilty of spying. While about 8,400 good employees would pass the test, 1,600 careers would be ruined.

Although government officials commissioned the study, they didn't like the results, so they have decided, apparently, to continue to use the polygraph in the war on terrorism. As reported by physicist Robert Park in his weekly electronic newsletter What's New, about 8,000 employees at the Los Alamos National Laboratory have been notified that they will be subjected to random polygraph tests.

Many researchers say that the standard polygraph based on blood, breathing and perspiration rates is a dead end and that the next-generation "lie detector" will involve a brain scan.

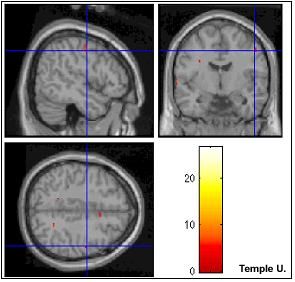

Researchers at Temple University in Philadelphia have found that certain regions of the brain seem to be implicated in lying, and these can be detected by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans. This research is in its very early stages, however. And such a truth-detecting device could still be flawed, for some people are so good a lying that the lies become their truths.

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books “Bad Medicine” and “Food At Work.” Got a question about Bad Medicine? Email Wanjek. If it’s really bad, he just might answer it in a future column. Bad Medicine appears each Tuesday on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus