Will USDA's New 'Plate' Icon Make a Difference in American Diets?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

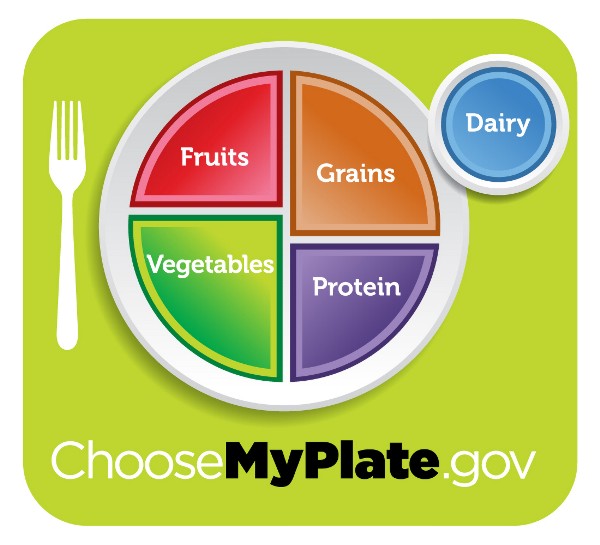

The U.S. Department of Agriculture unveiled a new icon today designed to assist Americans in their daily food choices.

Called MyPlate, the icon represents a plate of food and replaces the familiar food pyramid that has been used to educate Americans on nutrition since 1992.

The plate is divided into four differently sized sections to represent the relative amounts of grains, protein, fruits and vegetables people should eat. The fruit and vegetable sections fill half the plate. There is a small circle outside the plate to represent dairy. [See 6 Easy Ways to Eat More Fruits and Vegetables].

The goal of the plate is to provide a simple, easy way for Americans to think about building their meals.

"We needed something that made sense, not just in classrooms or laboratories, but at dinner tables," first lady Michelle Obama said in a news conference this morning.

"When it comes to eating, what's more useful than a plate?" Mrs. Obama said.

Nutritionists welcome the change and say the plate icon is easier to understand than the pyramid, which was confusing for many.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But nutritionists also caution that the new icon will make little difference unless proper nutrition education is provided to Americans.

"Thinking that some kind of icon is going to change habits is misguided," said Katherine Tallmadge, a registered dietitian and author of "Diet Simple" (LifeLine Press, 2011). "Icons don’t change eating habits," she said. "Whether it's a pyramid or a plate, what's going to change eating habits is nutrition education," Tallmadge told MyHealthNewsDaily yesterday.

Tallmadge applauded the government for the steps it's taking, but said that it is not enough. The budget for nutrition education should be increased, she said. Nutrition should be taught in schools and efforts should be made to ensure the food served as schools is healthy, she said.

Mrs. Obama also said the food plate alone can't fight the obesity epidemic. Communities need access to affordable fruits and vegetables and parents need to make the right choices for their families, she said.

Pyramid confusion

The food pyramid was adopted by the Department of Agriculture in 1992, and was revised in 2005. The original version had six food groups stacked atop each other, with grains, fruits and vegetables toward the bottom, dairy and protein in the middle, and fats and sweets at the top. The pyramid shape was meant to symbolize the need to eat more servings of the base groups and only small amounts of the higher groups.

The 2005 version, known as MyPyramid, was divided into vertical sections to represent the food groups, and included a human figure climbing up the side of the pyramid to represent exercise.

"Unfortunately, it just wasn’t really accepted well as a tool," said Heather Mangieri, a nutrition consultant and spokesperson for the American Dietetic Association. "I think there was lot of confusion as to how to use it," Mangieri said.

"It just simply is too complex to serve as a quick, easy guide for busy American families," Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said at the press conference.

Mangieri said the pyramid worked when she used it in nutritional counseling, but "consumers needed a lot of face-to-face, one-on-one education to understand how to use it."

New plate

Mangieri said the new design will provide an easy way to show consumers what to eat.

"It's a great visual to remind people what our plate should look like," she said. But she agrees nutrition education is required. "This is not going to solve our obesity epidemic," she said.

The MyPlate message also encourages people to avoid oversized portions, switch to fat-free or low-fat milk and make half the grains you consume whole grains.

Pass it on: The new MyPlate icon encourages Americans to make half their plate fruits and vegetables, but nutritionists say it's unlikely to change Americans' unhealthy eating habits.

Follow MyHealthNewsDaily staff writer Rachael Rettner on Twitter @RachaelRettner.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus