Faraway Volcanoes Shrunk the Mighty Nile

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

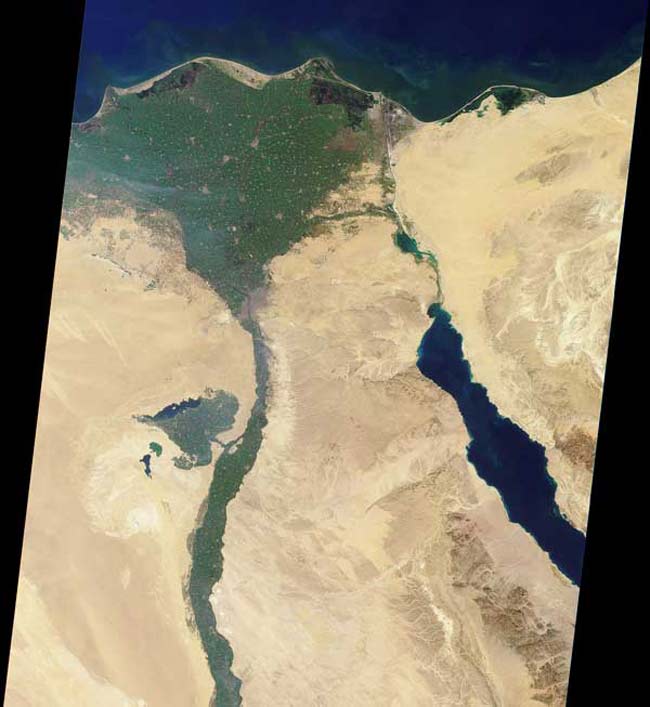

Volcanic eruptions on Iceland generated a cascade of events that led to record low levels of water in the Nile River in Africa and brought famine to the region more than two centuries ago, a new study concludes.

The findings will inform climate forecasting related to future volcanic activity.

From June 1783 through February 1784, a series of 10 eruptions from the Laki Craters on this European island in the North Atlantic changed atmospheric conditions in most of the Northern Hemisphere.

Unusual temperature and precipitation patterns peaked in the summer of 1783, causing below normal rainfall in most of the Nile drainage basin and therefore record low levels in the mighty river for up to one year following the eruptions.

When volcanic eruptions occur, large amounts of sulfur dioxide are released into the atmosphere. When this gas combines with water vapor, aerosol particles form. These particles reflect sunlight back to space and therefore cool average temperatures on Earth.

Researchers used computer models to simulate how Iceland's Laki eruptions affected temperature and rainfall levels over the stretch of land from the Atlantic ocean to the "horn of Africa," known as the Sahel.?

Simulations showed that the aerosols formed by the eruptions cooled average temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere by up to 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit. Tree ring data in Alaska and Siberia also showed reduced growth during the same summer, signifying cooler than normal weather.?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The abnormally cool temperatures reduced the temperature difference between the land masses of Africa and Eurasia and their respective water masses, the Atlantic and Indian oceans. Typically, a sharp contrast in temperature between land and sea drives roaring monsoon winds. Monsoons are seasonal shifts in wind direction that signify the beginning of the rainy season.

The lack of monsoons led to a reduction in cloud cover over the Sahel of Africa, southern Arabian Peninsula and India that summer. This caused temperatures to increase by as much as 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit and induced drought in the region. The resulting food shortage reduced the population of the Nile Valley by a sixth.

?

"Some of the driest weather occurred over the Nile and Niger River watersheds," said lead author Luke Oman, a researcher from Rutgers University, NJ. "The relative lack of cloud cover and increased temperature likely amplified evaporation, further lessening water available for run-off."

This dry weather corresponded with record low river water levels from 1783 to 1784.

"These findings may help us improve our predictions of climate response following the next strong high-latitude eruption, specifically concerning changes in temperature and precipitation," Oman said. "Many societies are very dependent on seasonal precipitation for their livelihoods, and these predictions may ultimately allow communities time to plan for consequences, including impacts on regional food and water supplies."

The study was detailed in the Sept. 30 issue of the American Geophysical Union's Geophysical Research Letters.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus