Stand Down: Black Holes Won't Destroy Earth

The world's largest, most powerful particle smasher probably won't generate any planet-gobbling black holes, according to a new analysis.

That's contrary to suggestions in a news article Wednesday that invoked a possible doomsday scenario and said black holes created by the collider could stick around longer than predicted.

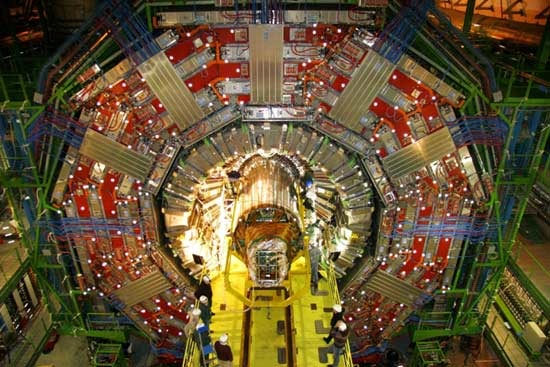

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a 17-mile (27-kilometer) circular tunnel running 300 feet (91 meters) underground at the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN) near Geneva, is expected to recreate the conditions that occurred a fraction of a second after the Big Bang, the theoretical instant in which the universe was born from an incredibly small point.

By smashing protons together at nearly the speed of light, the LHC could help to solve mysteries about the origin of mass and the reasons for more matter than antimatter in the universe.

(The LHC was shut down last year after a helium leak was discovered within days of its initial powering up. The machine is scheduled to re-start again some time this year, according to CERN.)

Scientists have speculated the proton-to-proton collisions could possibly generate microscopic black holes. These black holes would be orders of magnitude smaller and less massive than the gravity wells produced by the collapse of stars and known to exist in the universe, said Howard Gordon of Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, who also works at the LHC.

Even still, fears arose in the past few years that the LHC could churn out a black hole that would gobble up everything in sight, including our planet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Why the fears? "I think it's the confusion between the massive black holes in the universe and these microscopic black holes that possibly could get created," Gordon told LiveScience. "It's a difference in scale."

Black-hole model

The new analysis, detailed online at ArXiv.org, a repository for new research papers, suggests again that the LHC probably can't generate a catastrophic black hole.

Gordon said the analysis is based on a theoretical model and that further research is needed to confirm the results.

Roberto Casadio of the University of Bologna in Italy and his University of Alabama colleagues Benjamin Harms and Sergio Fabi based their theoretical model on the so-called Randall-Sundrum brane-world scenario, in which the four-dimensional universe is embedded within a five-dimensional space.

"All we're doing is taking a model of our space-time, where we live, and exploring the consequences," Harms said during a telephone interview. "And our exploration shows that black holes could not grow large enough to become catastrophic in the sense that they could do damage to the Earth or anything in the Earth."

He added, "What we found was that if black holes are created at the LHC, they would not be able to grow to catastrophic size because the accretion rate is simply not great enough to offset the evaporation rate."

In fact, the model showed that once a black hole is created by the LHC (if that were to happen), the only way to get the black hole to grow would be "to extend the size of one of the parameters in our model beyond a physically accepted value," so beyond what is physically possible.

And then, such a black hole would evaporate, and essentially vanish, within one-trillionth to one-millionth of a second, the model showed. While the black holes might not truly vanish, their masses would become so small they would have no effect on Earth.

One small caveat is that the results only apply to Earth because they depend partly on the density of material through which the black holes are traveling.

Creating black holes

"Large Hadron Collider had a tremendous amount of publicity last year because of the black hole speculations," Gordon said, adding, "We don't know for sure we're even going to see black holes in the Large Hadron Collider."

Here's the logic behind the LHC generating microscopic black holes:

Various models of the universe suggest extra dimensions (other than those of space and time) exist and are folded up into sizes ranging from that of a proton to as big as a fraction of a millimeter. The models go on to suggest that at distances comparable to such sizes, gravity becomes far stronger. If this is true, the collider could smash enough energy together to generate gravitational collapses that produce black holes.

Researchers have calculated that under such scenarios, the accelerator could create a microscopic black hole anywhere from every second to every day.

Harmless black holes

Physicists have repeatedly said that fears about these artificial black holes are "groundless."

For instance, microscopic black holes would probably lose more mass than they absorb and so would evaporate immediately.

Say a black hole was created and that black hole was stable. "Then their interactions would be very weak. They would pass harmlessly into space. They would vanish," Gordon said, referring to stable black holes with no electrical charge.

In addition, as CERN scientists have pointed out, Earth is bathed with cosmic rays powerful enough to create black holes, and the planet hasn't been destroyed yet.

At the end of the day, Gordon said, the LHC is safe and so are we.

"We're expecting the discoveries at the Large Hadron Collider to be significant and exciting, but we are pretty sure that the collider is safe and will not be causing any trouble to people living on Earth," Gordon said.

- Will the Large Hadron Collider Destroy Earth?

- Despite Rumors, Black Hole Factory Will Not Destroy Earth

- Search for Magical Dark Matter Gets Real

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus