Breakthrough: Mysterious Antimatter Created and Captured

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

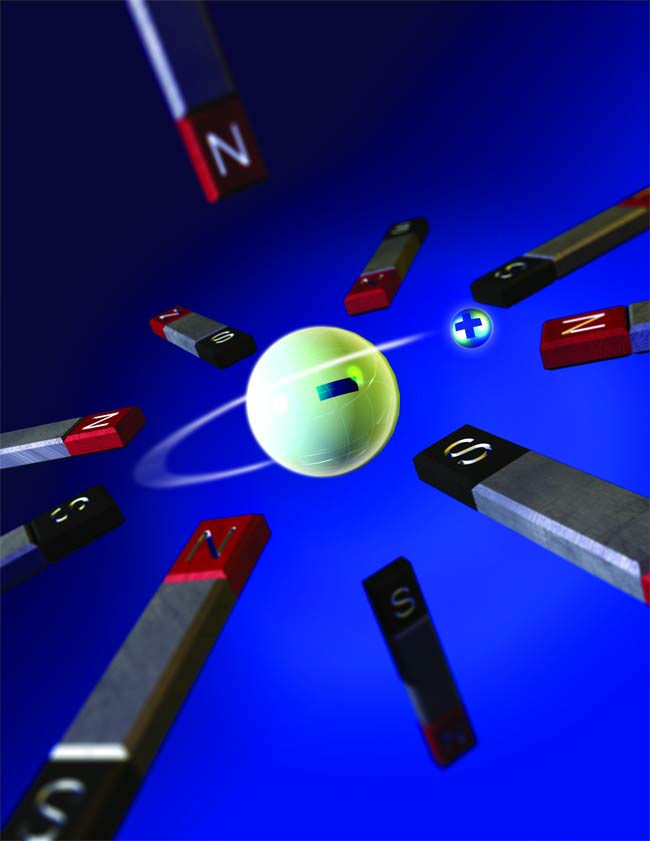

Scientists have created antimatter in the form of antihydrogen, demonstrating how it's possible to capture and release it.

The development could help researchers devise laboratory experiments to learn more about this strange substance, which mostly disappeared from the universe shortly after the Big Bang 14 billion years ago.

Trapping any form of antimatter is difficult, because as soon as it meets normal matter – the stuff Earth and everything on it is made out of – the two annihilate each other in powerful explosions.

In a new study, physicists at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) in Geneva were able to create 38 antihydrogen atoms and preserve each for more than one-tenth of a second. The project was part of the ALPHA (Antihydrogen Laser PHysics Apparatus) experiment, an international collaboration that includes physicists from the University of California, Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL).

The antihydrogen atoms are composed of a positron (an antimatter electron) orbiting an antiproton nucleus.

"We are getting close to the point at which we can do some classes of experiments on the properties of antihydrogen," said Joel Fajans, a University of California, Berkeley professor of physics, and LBNL faculty scientist. "Since no one has been able to make these types of measurements on antimatter atoms at all, it's a good start."

Antimatter, first predicted by physicist Paul Dirac in 1931, has the opposite charge of normal matter and annihilates completely in a flash of energy upon interaction with normal matter. Antimatter is produced during high-energy particle interactions on Earth and in some decays of radioactive elements.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 1955, University of California, Berkeley physicists Emilio Segre and Owen Chamberlain created antiprotons in the Bevatron accelerator at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (now called Lawrence Berkeley), confirming their existence and earning the scientists the 1959 Nobel Prize in physics.

To create antihydrogen and keep it from immediately annihilating, the ALPHA team cooled antiprotons and compressed them into a matchstick-size cloud. Then the researchers nudged this cloud of cold, compressed antiprotons so it overlapped with a like-size positron cloud, where the two particles mated to form antihydrogen.

All this happened inside a magnetic bottle that traps the antihydrogen atoms. The magnetic trap is a specially configured magnetic field that uses an unusual and expensive superconducting magnet to prevent the antimatter particles from running into the edges of the bottle – which is made of normal matter and would annihilate with the antimatter on contact.

"For the moment, we keep antihydrogen atoms around for at least 172 milliseconds – about a sixth of a second – long enough to make sure we have trapped them," said Jonathan Wurtele, a University of California, Berkeley professor of physics and LBNL faculty scientist.

The team's results will be published online Nov. 17 in the journal Nature.

- Image Gallery: Behind the Scenes at a Huge U.S. Atom Smasher

- What is Antimatter?

- Twisted Physics: 7 Recent Mind-Blowing Findings

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus