How long can organs stay outside the body before being transplanted?

Depending on the organ, the time can range from a few hours to a day and a half.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When it comes to organ transplant surgery, doctors are racing against the clock — and time is not on their side.

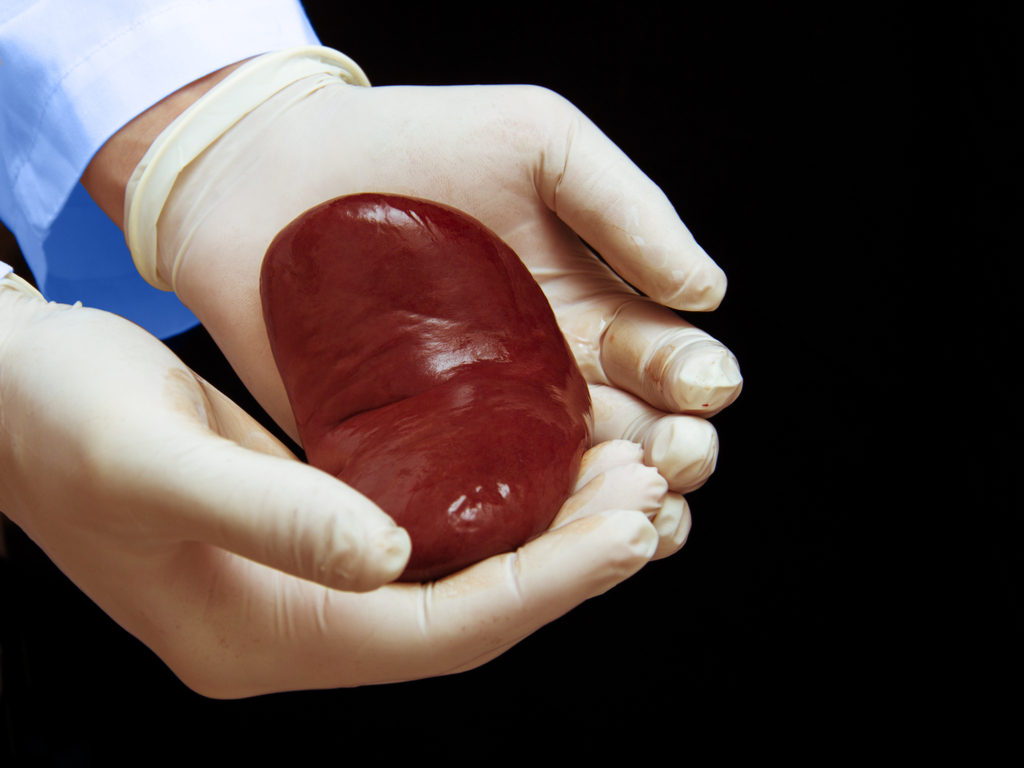

A team of clinicians must first remove the organ from its donor, sets of gloved hands coordinating to deftly cleave tissue from the body. Doctors then prep the harvested organ for transport to its recipient, who may be hours away by plane. Once the organ reaches its destination, the transplant operation can finally commence; again, surgeons must work swiftly to ensure both the patient's safety and the organ's viability.

This description may make organ transplant surgery sound like a TV drama, with medical personnel sprinting through hospital corridors carrying coolers packed with body parts. But all the rushing about raises a question that's much more important than a TV show: How long can an organ last outside the body and remain fit for transplantation?

It depends on the organ. For now, the time window can be between 4 and 36 hours. But someday, doctors hope to be able to maintain organs for weeks on end.

Related: 12 Amazing Images in Medicine

Organs on ice

In 2018, more than 36,500 organ transplants took place in the U.S. alone, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). By far, kidneys were the most commonly transplanted organ, with more than 21,000 transplants taking place last year. The next most commonly transplanted organs were the liver, heart and lung, in that order, followed by pancreas, intestine and multiorgan transplantations.

Most organs are placed in "static cold storage" after they're harvested, meaning that the organ is deposited in a cooler full of ice, according to a 2019 report in the Journal of International Medical Research.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The original idea for cold preservation is very much like when we put our food in the refrigerator," said Dr. Mingyao Liu, the director of the Institute of Medical Science and a professor of surgery, medicine and physiology at the University of Toronto.

Before placing an organ in cold storage, doctors first flush the tissue with a "preservation solution" to protect the organ from damage caused by the extreme cold, Liu told Live Science.

At body temperature, cells pump chemicals in and out of their membranes in order to maintain low concentrations of sodium and high concentrations of potassium within the cell. But cells that are cold can't pump efficiently. Chemicals leak across their membranes, and over time, the leaky cells swell up with excess fluid, sustaining serious damage. Preservation solutions help delay this damage by keeping sodium and potassium levels in check. These solutions can also contain nutrients and antioxidants to sustain the cells and subdue inflammation, Liu said. In combination with ice and a cooler, preservation solutions can keep organs viable for hours after harvest.

At temperatures between 32 and 39 degrees Fahrenheit (0 and 4 degrees Celsius), cell metabolism falls to about 5% of its normal rate, so tissues burn through their energy stores far more slowly and require less oxygen to sustain their activity. Because of this, cooling an organ helps delay the onset of ischemia, a condition in which tissue becomes damaged or dysfunctional due to a lack of oxygen.

Putting an organ on ice also stretches its cells' limited energy stores, preventing harmful metabolites from building up and breaking down the organ's tissues, according to a 2018 report in the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine.

Among commonly transplanted organs, hearts lose viability the fastest when stored in a cooler, said Dr. Brian Lima, the director of heart transplantation surgery at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, New York. Ideally, a heart shouldn't be placed in static cold storage for more than 4 to 6 hours, he said. At the 4-hour mark, heart cell function begins to fail and the likelihood that the organ will malfunction in its recipient rises dramatically. Transplant organ failure, known as primary graft dysfunction, is the "most feared complication" associated with solid organ transplants, Lima said.

"The heart … is most sensitive to lack of blood flow," Lima said. "The kidneys, on the other hand, are very resilient." Harvested kidneys can remain viable for 24 to 36 hours in cold storage, longer than any of the other top-four transplant organs. Lungs can remain viable for 6 to 8 hours, Lima said, and the liver can remain in cold storage for about 12 hours, according to Dr. James Markmann, head of the Division of Transplantation at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Related: Top 10 Amazing Facts About Your Heart

An alternate method

Although low tech, the ice cooler method "offers a simple and effective way to preserve and transport organs" and has been widely used since the 1960s, according to the 2018 report by Liu. But the technique is not without its drawbacks. Not only do organs in cold storage lose viability within hours, but also, doctors have no way to assess the quality of the chilled organs, Liu said.

Basically, no objective test can tell clinicians if an organ is still functional when the organ in question sits in a frigid cooler, its cell metabolism winding down in slow motion. However, one alternative to cold storage does allow doctors to check on organs before they're transplanted, and this option may soon become more commonplace, experts told Live Science.

This alternate preservation method, known as perfusion, involves hooking up a harvested organ to a machine that pumps oxygen- and nutrient-rich fluid through the organ's tissues, as the heart would do in the body, according to the 2018 report from the Yale journal. While plugged into the machine, as the organ metabolizes energy and produces waste, its sugar stores are replenished and its toxic metabolites cleared away.

Before surgeons harvest an organ, the donor's heart stops pumping oxygenated blood to the tissue for a period of time, which causes damage. Placing an organ in a perfusion machine may give the tissue a chance to recover, Markmann said. In addition, clinicians can check in on the organ by monitoring levels of the metabolite lactate circulating in the system, he said. Cells use lactate during normal metabolic functions, so "if the organ is working well, the lactate should be cleared" over time, Markmann said.

"Lactate is at best a crude metabolic measure of perfusion through the body," but it still serves as a superior measure compared to eyeballing a near-frozen organ before transplantation, Lima added. Depending on the organ, doctors can also assess the health of the tissue by other measurements, such as the production of bile by the liver.

Related: 27 Oddest Medical Cases

Could perfusion keep organs healthy for longer?

Some perfusion systems still require that the organ be cooled down as part of the preservation process, but within the last 20 years, several research groups have opted to keep the organ warm and flood the tissues with warm blood. At temperatures between 68 and 92 F (20 and33 C), isolated organs function much as they do in the human body. Both cold and warm perfusion systems are now widely used in Australia and the U.K., but most of these devices remain in clinical trials in the U.S.

However, one perfusion system in the U.S. made headlines in December as part of a first-of-its-kind heart transplantation. Doctors at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, removed a patient's heart after it had stopped beating; they then essentially "reanimated" the organ using a warm perfusion system, CNN reported. Typically, hearts are removed from brain-dead donors before the organ stops beating, to avoid extensive damage from ischemia. Doctors previously "reanimated" pediatric hearts in the U.S., but they'd never used the system on an adult organ. In countries that have used the system for years, the donor pool of acceptable hearts has expanded by about 30% to 40%, Lima said.

"If that translates into the United States, we're talking about big, big numbers," he added.

Dr. Jacob Schroder, a Duke University assistant professor of surgery and one of the surgeons who helped perform the landmark heart transplant, told CNN that using the system nationwide could "increase the donor pool and number of [heart] transplants by 30%."

Although the donor pool may expand, would the condition of the organs improve? As of yet, few studies have directly compared cooler storage to perfusion, but anecdotally, perfused organs generally seem to fare better.

For instance, in one trial comparing a liver perfusion system to standard cold storage, doctors rejected only 16 perfused livers, compared to 32 that came from coolers, and the perfused organs appeared less damaged, according to Stat News. Liu said that he's observed similar trends in his own work with lung transplants. Liu and his colleagues developed an "ex vivo perfusion system" for lungs; prior to its introduction, fewer than 20% of donor lungs were successfully transplanted at his university's hospital. Now, the program has expanded its activity by 70%, "with excellent outcomes," according to a 2018 report.

Typically, lungs remain hooked up to the perfusion system for 4 to 6 hours, but experimental work with animal organs suggests that perfused lungs could remain viable for 12 to 18, and maybe even up to 36 hours, Liu said. He added that, someday, an organ could be perfused for weeks. The longer that organs can be left on the system, the more time clinicians would have to repair damaged tissue. Liu and his colleagues are now investigating how inflammation and cell death can be inhibited in perfused lungs. But in the future, perhaps organs could be treated with gene or stem cell therapies while hooked to a perfusion machine, he said.

For now, however, most donated organs still travel to their recipients nestled in coolers of melting ice. Why?

"Quite honestly, the hurdle with [perfusion] is the cost," Lima said. A perfusion system for a single organ can cost several thousand dollars, which obviously surpasses the price of a standard cooler, he said. As few studies have compared perfusion to standard cold storage, no "earth-shattering data" exist that could convince hospitals to make the switch nationwide.

But given the recent success of the Duke heart transplant, Lima said that perfusion may soon become the standard of care.

- 9 New Ways to Keep Your Heart Healthy

- Top 10 Useless Limbs (and Other Vestigial Organs)

- Could Humans Ever Regenerate a Limb?

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus