Adults Struggle with What Used to Be Child's Blood Disorder

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It's been 100 years since sickle cell disease, a hereditary blood disorder, was first discovered and described in Western society.

While researchers and doctors have come a long way in terms of their understanding of the disease and providing screening and treatment for children, adults with the condition still face many challenges, including misperceptions and lack of access to proper care. As a result patients often end up in the emergency room for treatment and help with pain episodes — a hallmark of the condition.

In fact, 41 percent of patients ages 18 to 30 who are hospitalized in acute care end up rehospitalized within 30 days, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in April. That's much higher than the rate for other diseases, including heart failure (16 percent) and diabetes (20 percent.) The findings suggest many patients aren't receiving the proper care when hospitalized or during a follow-up visit.

In some ways, the problems faced by sickle cell patients are simply a reflection of the U.S. health care system, which has inadequacies in meeting the needs of adults, especially those who have a chronic disease or are poor, experts say.

But there are issues specific to sickle cell disease.

"Thanks to advances in sickle cell disease care, patients with sickle cell disease now live a lot longer than they used to," said Dr. David Brousseau, a professor of pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin who conducted the JAMA study. "Thirty or 40 years ago, the majority died during childhood, and so a lot of the treating and care of sickle cell disease patients was focused in the pediatric population," he said. "I think there are more established sickle cell specialists in the pediatric realm than there are in the adult realm, in large part because it's been a relatively recent shift to having lots of sickle cell disease patients living long enough to get to older adulthood."

Now doctors and organizations are working together to increase awareness and create consistent treatment guidelines for the condition.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is sickle cell disease?

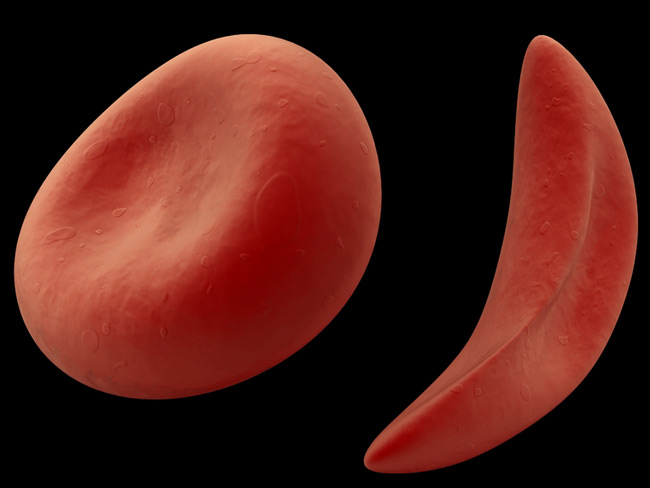

Sickle cell disease gets its name from the distorted shape of a patient's red blood cells, which are sometimes C-shaped rather than the normal doughnut shape. The cells' disfigurement comes from the presence of abnormal hemoglobin — a protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body. [Read more about sickle cell anemia].

The disease primarily affects those who descend from tropical or subtropical countries, including Africa, South America, Central America and India. In the United States, 70,000 to 100,000 African Americans are estimated to have sickle cell anemia, or 1 out of every 500 births in this population, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The abnormal sickle cells are less flexible than normal red blood cells, which can cause a number of problems. The cells can block blood vessels and restrict blood flow, which can lead to pain, organ and nerve damage and stroke.

The sickle cells also don't live as long as normal red blood cells, lasting around 20 days instead of the usual three months. As a result, patients experience anemia.

Current treatments involve blood transfusions to treat anemia and help prevent stroke, and pain medication for pain episodes. The only sickle cell-specific drug available, known as hydroxyurea, helps alleviate pain and can reduce the rate of mortality in patients. Experts believe the drug is not being used as often as it should due to lack of awareness from both doctors and patients

Hospitalized and rehospitalized

Though treatment has gotten to the point where patients are living much longer than they did some decades ago, it may not be adequate. For instance, Brousseau's JAMA study looked at hospitalization rates for 21,112 sickle cell patients of all ages in eight U.S. states, finding one-third required a rehospitalization within 30 days.

However, Brousseau notes that while the rehospitalization rate is considered a good indicator of quality of care for other diseases, researchers aren't sure yet if the same is true for sickle cell disease — one hospitalization for pain might be entirely unrelated to the next. Nonetheless, high rate should be a "red flag that something could be wrong," he said.

Brousseau hopes the work spurs more studies to find out why these numbers are so high and figure out ways to bring them down.

Child to adult

One reason rehospitalizations for adults might be so high is that care for adults isn't as well established as it is for children.

"Sickle cell is a [disease] that, in my opinion, reflects the benefits and problems of the U.S. healthcare," said Elliott Vichinsky, a hematologist at Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute (CHORI) in California. "We have really outstanding technology, but it's difficult for many reasons to deliver it to the adult sickle cell patients."

One of those problems is providing health insurance to young adults as they transition out of childhood.

"For many people, once you hit your young adult years, your guaranteed insurance may disappear, your primary care pediatrician is no longer seeing you, so you're in this transition," Brousseau said. "I think that's one of the potential concerning areas in the sickle cell population, is that they aren't transitioned across the country particularly well."

Another problem for adults is their care tends to be not as well coordinated as it is for kids.

"You have a pediatrician who will consult with the hematologist who might consult with the pulmonologists who might consult with the cardiologists," said Melissa Creary, a health scientist at the CDC's National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. "And when you become an adult it’s a little bit harder to access all of these people to coordinate the care that you need."

African Americans are also overrepresented among the nation's poor — a population with less access to health care benefits. "If you qualified for insurance at a young age, because of your poverty level, you might lose some of that when you become an adult," Brousseau said.

An obstacle more specific to sickle cell is that doctors tend to be less familiar with the disease in adults in general. "I think the training programs haven't been preparing residents to take care of adults with sickle cell disease because there just weren’t that many," Brousseau said. There are also fewer specialists, including adult hematologists (doctors who study blood-related illnesses), that focus on the condition.

As a result, some adult sickle cell patients get their care from pediatric centers, Brousseau said. While some doctors are stepping in to fill the need for physicians with adult sickle cell knowledge, at present, there aren't enough.

"It seems like there is an increase now, but until that increase is sufficient, I think you're going to continue to have these people who transition from pediatric to adult care who get a little lost in the system and don't feel like they have that medical home that people do when they're kids," Brousseau said.

Disease misperceptions

Doctors are often unaware of how much pain the condition can cause and how much medication it requires, experts say. As a result, patients seeking pain relief might be suspected of soliciting drugs.

"In order to treat the pain, high doses of narcotics are often needed," Creary said. "And, to further compound that situation, patients who have sickle cell disease often are very well in tune with their body and know exactly the amount of medication and what medication they need."

That meticulous knowledge can cause red flags.

"They may present to an emergency room department and tell the doctor that they're in pain and they need x, y and z medication and they need this much of it, and they already know that if you give them this much it's not going to work," she said. "And that comes off as certainly suspicious behavior in the eyes of many doctors."

Future remedies

Physicians and organizations are undertaking a number of projects to help remedy the situation.

In one project being conducted by the CDC and the National Institutes of Health, scientists are trying to find out exactly how many sickle cell patients there are in the United States, since it's unclear whether the present estimates are accurate. Although people are now screened at birth for the disease, immigrants and those who were born before screening would not have been counted. The project, known as RUSH, will also involve collecting information on who is treating these patients and whether they have sufficient access to care.

"We need to know, how many patients there are; we need to know [if] they're being seen, or if they're not being seen. And once we get that information we'll be able to hopefully address the gaps in that health care utilization," Creary said.

The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute is also developing new guidelines to set a consistent standard of care for the disease and which will be made widely available to doctors.

This information will be especially helpful in rural areas, which tend to lack specialized sickle cell disease centers and have smaller populations of people with the condition.

"You go to non-urban areas, specifically if you go to non-specialty centers, you're just going to a regular practioner, the chances of them knowing about sickle cell disease are kind of slim," Creary said.

Care centers throughout the country have also been given grants to help educate health care providers about proper sickle cell treatment, including the use of sickle cell drug hydroxyurea. "Some people are being seen by primary care providers but somehow the information hasn't been as well disseminated about the value of hydroxyurea," said Marsha Treadwell, a sickle cell disease researcher at CHORI, who is a recipient of one of the grants.

Efforts are also being made to improve care at the global level. Doctors and health professionals from all over the world met last week at the First Global Congress on Sickle Cell Disease in Accra, Ghana. The aim was to discuss a variety of issues related to sickle cell disease management, to share information on the condition and figure out ways for care to be consistent across countries.

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases

- 7 Solid Health Tips That No Longer Apply

- 7 Ways to Raise Your Risk of Stroke

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus