Scent of a Woman's Tears Lowers Men's Desire

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

What a downer! Men who smell a woman's tears experience a dip in both sexual arousal and testosterone, a new study finds.

The libido-dampening effect occurred even when the men never saw the women cry and didn't know they were sniffing tears, researchers report online today (Jan. 6) in the journal Science.

The results are the first to suggest that humans can chemically communicate with tears.

"We conclude that there is a chemosignal in human tears, and at least one of the things the chemosignal does is reduce sexual arousal," study researcher Noam Sobel, a neuroscientist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, told LiveScience.

An odorless signal

It's obvious that humans communicate both verbally and visually, but recent research has shown that chemosignals also carry lots of information. Chemosignals may be entirely odorless – in Sobel's study, participants were unable to tell the difference between tears and saline solution – but they affect both behavior and physiology.

Earlier work by Sobel and others found that male sweat can boost mood and sexual arousal in women, as well as bumping up their levels of the stress hormone cortisol. And a 2004 study published in the journal Hormones and Behavior found that the scent of a lactating woman's nursing pads could increase sexual desire in other women.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

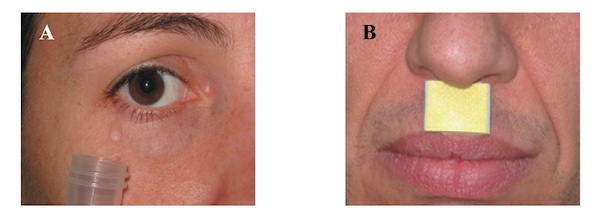

Scientists have found that emotional tears contain more protein than do the everyday tears that protect the eyes. Until now, however, chemical signals in tears had been found only in mice and blind mole rats. To investigate the phenomenon in humans, Sobel and his colleagues put out fliers recruiting people who could cry easily. They got about 70 responses (only one of them from a man), he said. The researchers screened the volunteers and found the three best criers – women who could produce at least a milliliter of tears while watching a sad movie.

The researchers then had 24 men sniff both saline and the women's tears. Both the tears and saline had been allowed to roll down the women's cheeks, as a way to control for any odors in their skin or sweat.

None of the men could tell the difference between the two samples, and even the experimenter was kept in the dark about which she was presenting. The men then saw photos of women's faces, which they rated for sadness and sexual attractiveness. [Read Sexual Pheromones: Myth or Reality?]

"To our surprise, there was absolutely no influence on sadness or empathy or anything of that sort that we had expected," Sobel said. However, "sexual arousal dropped after sniffing tears."

Questions about crying

The researchers tried the experiment again, this time priming 50 male volunteers for sadness by showing them a depressing video clip. Again, sniffing tears instead of saline didn't make men sadder. But it did lower their sexual arousal and their testosterone levels.

As a final experiment, the researchers repeated the tear-sniffing with 16 men who were situated inside a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine (fMRI). The fMRI shows patterns of blood flow in the brain, which coincide with brain activity.

Sure enough, the tears reduced activity in areas known to be involved in sexual arousal. Those areas included the hypothalamus, an almond-size structure just above the brainstem, and the left fusiform gyrus, which is on the surface of the left side of the brain.

The study was "very well done," said Charles Wysocki, a psychobiologist at the Monell Chemical Sense Center in Philadelphia.

"Tears contain proteins that are also found in the underarm," Wysocki told LiveScience. "And in the underarm they bind the chemicals that we think are involved with chemical communication, so it's quite possible that these proteins found in tears might be doing the same thing."

The finding is likely to remain controversial until researchers discover a specific chemical that causes the response, however. Sobel’s lab is now working to identify the compound in tears that sends the signal.

"There's something that's operating at a very low concentration to cause this effect," George Preti, an organic chemist at the Monell Center who wasn't involved in the study, told LiveScience. "It's obviously a molecule with a lot of oomph."

The study also raises questions of whether children's and men's tears send signals, and what signals are conveyed within one’s own gender by tears. Whether happy tears send a signal is another open question, Wysocki said.

"You can understand where women might not be aroused when they are, in fact, crying," Wysocki said. "And maybe they're telling the male, it's a chemical communication way of saying 'No' or at least 'Not now.' You can see that, it makes sense. But if doesn't make sense to have the same chemical signal being released when a guy gets back after a year of tour of duty and his wife greets him with tears of happiness and pleasure. I would speculate that those tears would be containing something else."

Given the newfound parallel between rodents and human tears, the idea that humans are the only mammals to cry emotional tears may be wrong, Sobel said.

"Human emotional tears were considered unique because they were considered purely an emotional response," he said. "But what we've shown is that they're a form of chemosignaling, at least in part, and that puts them on par with mice tears and mole-rat tears."

- New Theory for Why We Cry

- Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind

- Top 10 Things That Make Humans Special

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus