Ants Use Velcro Claws to Ambush Heavy Prey

To catch very large prey thousands of times their own weight, one South American ant hunts with the aid of hook-like claws much like those seen in Velcro.

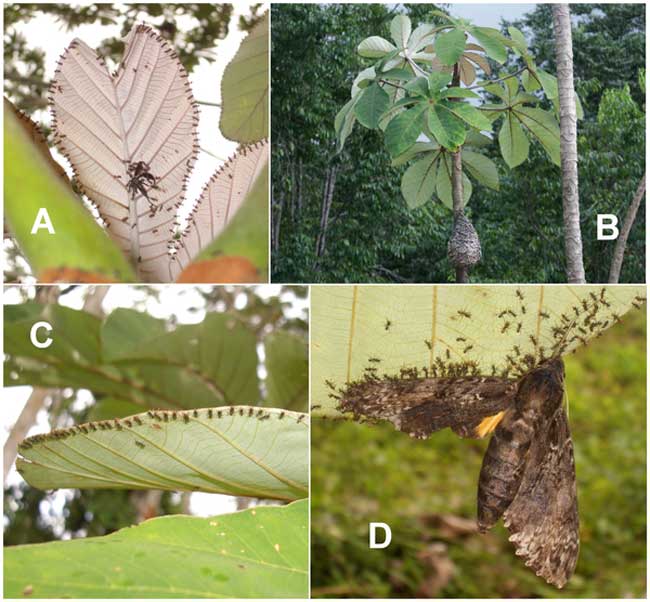

In the jungles of French Guiana, the ant Azteca andreae lives symbiotically with the trumpet tree, called Cecropia obtusa, which hosts colonies of the insects in its hollow stems. The benefits that such ant-friendly plants gain from these relationships include protection from plant-munching bugs the ants prey on. [See "Images: Ants of the World"]

In the course of their work in the rainforest, researcher Alain Dejean at the French National Center for Scientific Research and his colleagues spotted the ants capturing a locust thousands of times the size of a lone ant. Their investigations revealed the ants accomplished this feat with the aid of Velcro-like structures on the ants and the trees.

Made famous after NASA used it in spacesuits, Velcro was inspired by nature — specifically, the tiny hooks on seeds that latched onto the inventor's clothing. It consists of pieces of fabric covered with little hooks that fasten onto strips covered with tiny loops.

The scientists discovered that the ants wait to ambush their victims by hiding side-by-side near the edges of the leaves' velvety undersides with their jaws open, with some 850 ants per leaf on average.

When prey does land on the foliage to either seek shelter or nibble on leaves, the ants pounce en masse, rushing forward upside-down by latching onto the downy surfaces with their claws, much as hooks fasten onto loops in Velcro. This clinginess helps anchor the predators down for leverage, enabling ants in the first wave of the attack to hold onto targets so their partners can then spread the victims apart and carve them up.

When tested with string glued onto various weights and the free end near an ant, the scientists found that each ant had a firm enough grip on the leaves to hold onto loads up to 0.3 ounces (8 grams), equivalent amazingly to more than 5,700 times their own weight.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With the ambush strategy these claws enable, the researchers found the ants could bring down locusts a little more than 4 inches long (10.5 centimeters) and weighing some 0.7 ounces (18.61 grams), or 13,350 times that of a lone ant. That would be equivalent to a roughly 2-million-pound catch (934,500 kg) by a group of hunters each weighing about 154 pounds (70 kg).

The scientists detailed their findings online June 25 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus