Dinosaur Dads Watched Over Eggs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

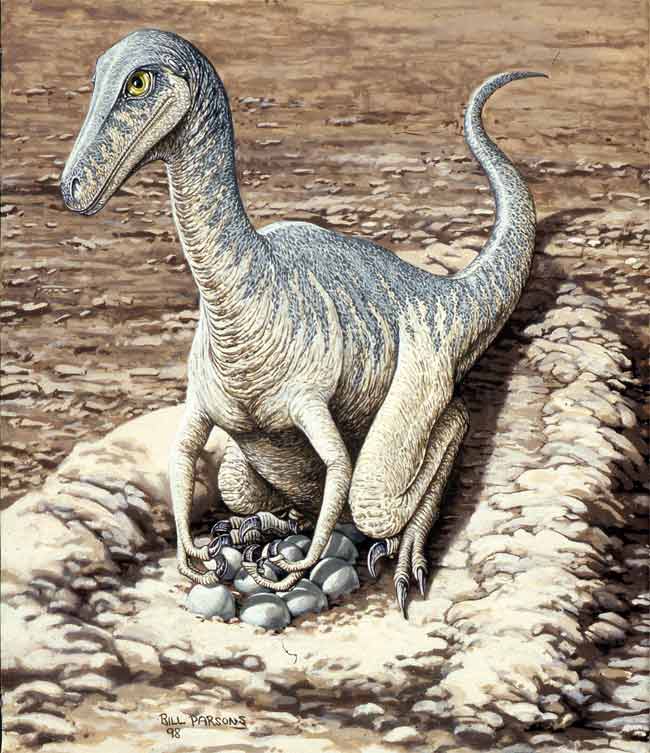

In families of some of the most vicious and carnivorous dinosaurs, dad took care of the developing eggs, possibly laid by more than one mom, a new study suggests.

Evidence for dino daddy daycare and potential polygamy comes from the fossilized remains of three dinosaurs sitting on nests. In the animal kingdom polygamy is common.

An analysis of these fossils supports growing research showing bird-like features and behaviors in non-avian dinosaurs, including, for some species, feathers and possibly flight.

The male's involvement in parenting is the latest example. In more than 90 percent of living bird species, males participate in parental care of young. That's compared with just 5 percent of mammals.

"The results are very interesting, although not surprising considering all the other characteristics that are similar between living birds and meat-eating dinosaurs," said Darla Zelenitsky, a paleontologist at the University of Calgary in Alberta, who was not involved in the new study. "This is one more piece of the bigger puzzle of learning about the evolution of birds from meat-eating dinosaurs."

The analysis, detailed in the Dec. 19 issue of the journal Science, reveals this trend of dad taking care of the eggs began millions of years ago, before flight evolved in birds, and has been passed down over evolutionary time by the birds' ancient relatives, the dinosaurs.

"One of the things I like about this study is it brings fossils to life," said researcher Jason Moore of Texas A&M University. "It lets us view ancient ecosystems as functioning living entities, rather than just bones in the rock. And that these interactions in the past were as complicated and as amazing as anything we can see today."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Giant eggs

To figure out the dinosaur parenting strategy, the researchers looked at three species of maniraptoran dinosaurs — Troodon formosus, Oviraptor philoceratops and Citipati osmolskae. Paleontologists think birds derived from maniraptors (a group of theropods, or meat-eating dinosaurs) some 150 million years ago during the Jurassic Period.

The team specifically analyzed the size and number of eggs laid in the dinosaurs' clutches, which among other creatures alive today gives clues to who sat on the eggs.

"The basic argument is that if the mother is taking care of the eggs then she doesn’t have as much time to go out and feed and gain energy for herself, so she can't invest as much in her eggs," Moore told LiveScience. "She can't make her eggs very big, or she can't make loads of eggs because she can't get enough energy to build those eggs."

But if the male cares for the eggs, mom is free to snag meaty snacks and so can lay bigger, or more, eggs. Larger eggs generally lead to healthier offspring.

The researchers also compared this calculation of egg size and number with hundreds of living animals with different parenting styles, including crocodiles with maternal care, birds with two-parent care, birds with maternal care and those with paternal care.

The results showed the theropod data best matched that of birds with paternal care, that is, dads-only caring for the eggs.

Dinosaurs dads

Supporting this result, the researchers also didn't find any evidence for a layer of bone typically found in female birds, and some female dinosaurs, that are laying eggs or getting ready to lay eggs. This result suggests the male was actually sitting on the nest for the three dinosaur species found fossilized with eggs.

Moore says he is not certain whether these theropods actually incubated the eggs or cared for the young later on in life. Likely the father dinosaurs protected the nests from scavengers and ensured the nests remained at a healthy temperature while mom was out fattening up.

Some dinosaurs have been shown to lay one or two eggs every day or so. For instance, Troodon likely laid two eggs at a time for a total clutch of up to 30 eggs. And Moore speculates that perhaps the nest eggs came from several moms, with different females laying their daily eggs in a single nest, as is the case for ostriches. However, he adds there is no direct evidence for a polygamous lifestyle in dinosaurs.

With so few dinosaur nest fossils, Moore cautions that the evidence for paternal care isn't absolutely conclusive. "I would say the evidence is good," Moore said. "The difficulty is that we have so few specimens. To do a study like this and be absolutely conclusive we'd like to have 30 or 50 or 100 specimens, but the fossil record isn't like that."

David Varricchio of Montana State University and others participated in the work.

- Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly

- Birds of Prey: Spot Today's Dinosaurs

- Dino Quiz: Test Your Smarts

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus