Rare Look at Darwin and First Dinosaur Hunters

A set of 19th-century research publications about to go online reveals the work of famous European scientists, including Charles Darwin, who were obsessed with dinosaurs, pterodactyls, plesiosaurs and fossilized dung.

The first full description of a dinosaur is one of the topics covered in the Transactions of the Geological Society, which will be made available online for the first time on Dec. 17, as part of the Society’s Lyell collection. The Transactions represent the earliest systematic publishing by the Society, in print from 1811 to 1856. During this time they featured almost 350 papers, many of which have become classics, but complete print sets are extremely rare.

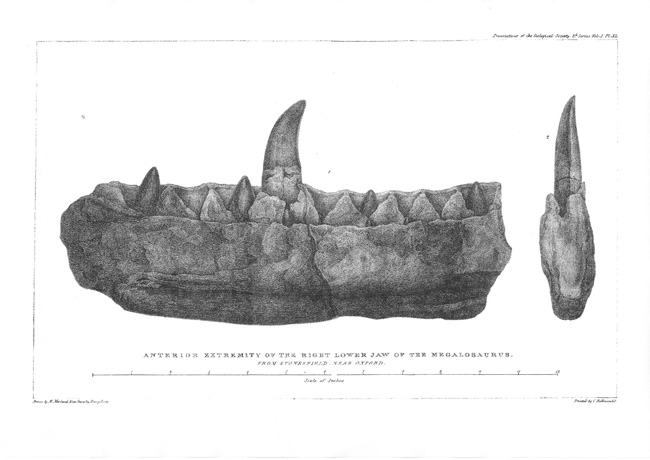

They include papers from world famous geologists such as Charles Darwin, William Buckland, Charles Lyell and Richard Owen. Owen, who played an important role in the founding of the Natural History Museum in London, was also behind the coining of the word "dinosauria," meaning "terrible lizard," in 1842. Megalosaurus, the first fully described dinosaur

Dinosaurs feature prominently among the Transactions, including several papers by Rev. William Buckland, who became the Society’s president in 1824. These include the first full description of a dinosaur, developed from lower jaw bones found at quarries near Oxford from a creature he named "Megalosaurus," and published in the Transactions in 1824 under the heading "Notice on the Megalosaurus or great Fossil Lizard of Stonesfield." Megalosaurs were carnivorous theropod dinosaurs. Buckland’s interest in dinosaur remains included more than bones. He also carried out a large amount of research into dinosaur coprolites, more commonly known as dung, much of which was published in the pages of the Transactions.

His 1829 paper, "On the Discovery of Coprolites, or Fossil Faeces, in the Lias at Lyme Regis," states that they have "undergone no process of rolling, but retain their natural form, as if they had fallen from the animal into soft mud, and there been preserved," later comparing them to "oblong pebbles or kidney-potatoes."

Dinosaur coprolites are so common that many people sell and collect them today. Of coprolites suspected to be from Ichthyosaurs (large marine reptiles that looked like fish and dolphins), Buckland notes that they seem to contain the bones of other Ichthyosaurs, suggesting that "these monsters of the ancient deep, like many of their successors in our modern oceans, may have devoured the smaller and weaker individuals of their own species."

Like many of the papers, this one contains references to Mary Anning, the famous fossil hunter of Lyme Regis. Elsewhere Buckland credits her directly with the discovery of a new species of Pterodactyl at Lime Regis in 1829, although the paper is published under his own name. Plesiosaurs and pterodactyls

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

New species discoveries feature prominently throughout the Transactions. In one of the earliest volumes from 1821, Henry de la Beche and William Conybeare report the discovery of "a new Fossil Animal, forming a link between the Ichthyosaurus and Crocodile," which they name Plesiosaurus. Plesiosaurs were carnivorous marine reptiles.

Elsewhere, in their 1840 report on fossils from the Siwalik Hills, Captain Probey Cautley and Dr. Hugh Falconer describe the numerous species they have uncovered there with some trepidation, particularly remains resembling giant tortoises: "as the Pterodactyle more than realised the most extravagant idea of the Winged Dragon, so does this huge Tortoise come up to the lofty conceptions of Hindoo mythology: and could we but recall the monsters to life, it were not difficult to imagine an elephant supported on its back." The world which was being gradually uncovered by these early scientists was an increasingly strange and disturbing one. In his report on the new species of pterodactyl at Lyme Regis, Buckland describes it as "a monster resembling nothing that has ever been seen or heard of upon earth, excepting the dragons of romance and heraldry." (Pterodactyls were flying reptiles. They are often mistaken for dinosaurs.)

He later considers the full extent of the frightening nature of "these early periods of our infant world," which featured "flocks of such-like creatures flying in the air, and shoals of no less monstrous Ichthyosauri and Plesiosauri swarming in the ocean, and gigantic crocodiles and tortoises crawling on the shores of the primaeval lakes and rivers." Darwin’s mold

With such an alarming and unfamiliar picture of the world being revealed by geology, it is not surprising that many of the authors attempted to reconcile what they found with their own religious beliefs.

Buckland in particular used what he saw to prove the biblical history of the Earth, arguing in an 1821 paper that the quartz rock and strata he saw at Lickey Hill in Worcestershire were evidence of a "universal and recent deluge." He goes on to cite the numerous animal remains found in these gravel beds, including elephant tusks, two Siberian rhinoceros skulls, stag horns and the bones of hippopotamuses. Not all the papers had quite such a dramatic impact on scientists’ world views. Among them is a work by Charles Darwin which is a far cry from his later epoch changing "On the Origin of Species."

The five page paper, "On the Formation of Mould," outlines Darwin’s researches, carried out at the suggestion of his father-in-law Josiah Wedgewood II, into the effects of the digestive processes of "the common earthworm" on layers of vegetable mould in fields around Maer Hall, the Wedgewood’s home in Staffordshire.

Published in 1840, it was written after Darwin returned from his voyage on the HMS Beagle, during his long period of developing his theory of natural selection. Darwin later devoted his last scientific book, published in 1881, to the subject, in a work entitled "The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms, with Observations on their Habits."

- Gallery: Darwin on Display

- Gallery: The World’s Biggest Beasts

- All About Dinosaurs

Robin Lloyd was a senior editor at Space.com and Live Science from 2007 to 2009. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Smith College and a Ph.D. and M.A. degree in sociology from the University of California at Santa Barbara. She is currently a freelance science writer based in New York City and a contributing editor at Scientific American, as well as an adjunct professor at New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus