These Ghostly Blue Clouds Only Appear at Night — And They're Made of Meteors

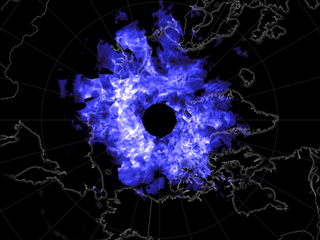

It looks like a ring of blue fire in the sky. But, in fact, that swirl of sapphire over the North Pole and Greenland is actually ice — that, and a bit of pulverized meteor dust.

They're called "noctilucent clouds," because they only appear after sunset. Blue and wispy, these moonlighting cirrus strands form high in the atmosphere in spring and summer, when the upper atmosphere starts to cool as the lower atmosphere warms. There, ice crystals hovering about 50 miles (80 kilometers) over Earth glom onto little particles of dust from smashed-up meteorites and other windblown sources, then condense into smoky ribbons of cloud. (The same phenomenon has been spotted on Mars.) [Gallery of the Craziest Clouds]

These are the highest clouds in the sky, according to the American Geophysical Union, and form so high up that they glow icy blue even after the sun appears to have passed below the horizon at ground level. Usually, they're only spotted at high latitudes in warm months; the ring of clouds above, shown in a composite image taken by NASA's Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM) spacecraft — a satellite that measures how much sunlight is being reflected into space by high-atmosphere clouds — appeared over Greenland on June 12, 2019.

However, according to NASA's Earth Observatory, noctilucent clouds like these have been creeping farther and farther south lately. At dusk on June 8, a sheet of noctilucent clouds was visible in 10 states, including Oregon, Minnesota, Michigan and Nevada. Those southward-creeping clouds seem to be part of a trend that has gotten more pronounced every year for more than a decade.

"Since the launch of AIM in 2007, researchers have found that noctilucent clouds are stretching to lower latitudes with greater frequency," NASA Earth Observatory managing editor Michael Carlowicz wrote in the blog post. "There is some evidence that this is a result of changes in the atmosphere, including more water vapor, due to climate change."

On the long list of ways that climate change is warping our world, an increased number of pretty blue meteor clouds is certainly one of the most welcome. So look up, and enjoy.

- Earth Pictures: Iconic Images of Earth from Space

- Aurora Photos: Northern Lights Dazzle in Night-Sky Images

- Strange & Shining: Gallery of Mysterious Night Lights

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.