Stock up on emergency supplies and get those galoshes ready — this year's hurricane season is likely to be a big one.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its outlook today (May 25) for the current hurricane season, which runs from June 1 to Nov. 30. People on the Atlantic Coast should be prepared for a wet and windy 2017 hurricane season.

This year, there is a 45 percent chance of an above-normal season, a 35 percent chance of a near-normal season and just a 20 percent chance of below-normal activity, NOAA reported.

That's because all of the ingredients needed to form and fuel a hurricane seem like they'll be aligned this year: "The outlook reflects our expectation of a weak or nonexistent El Niño, near- or above-average sea-surface temperatures across the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, and average or weaker-than-average vertical wind shear in that same region," said Gerry Bell, lead seasonal hurricane forecaster with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. [History of Destruction: 8 Great Hurricanes]

Many strong storms

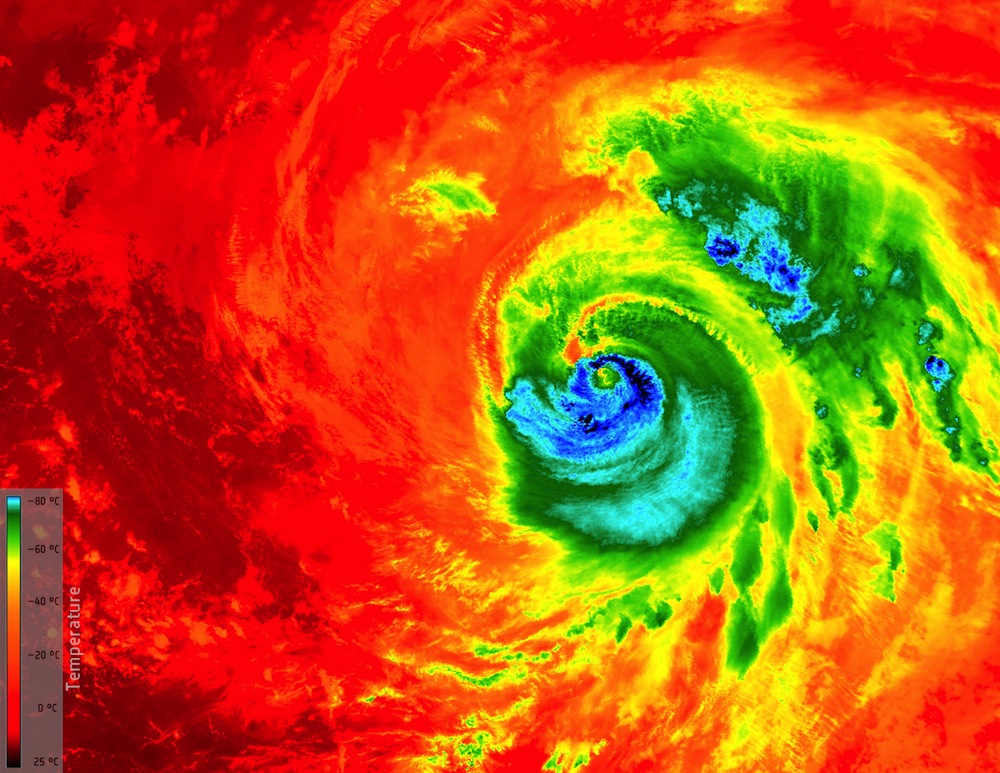

The above-normal designation means that people on the U.S. East Coast can expect to see between 11 and 17 "named" storms, which have sustained winds of 39 mph (62 km/h) or higher. Of those, between five and nine could become hurricanes, which are defined as storms with sustained winds of 74 mph (119 km/h) or higher. And anywhere from two to four of these storms could become major-category 3, 4 or 5 hurricanes, which means they would sustain winds of 111 mph (178 km/h) or higher.

Though the outlook predicts a stormy season, there's still substantial uncertainty in the prediction, Benjamin Friedman, NOAA's acting administrator, said in a news briefing.

Normally, a strong El Niño warms the water hovering near the equator in the Pacific, causing storms to brew in the Pacific while damping hurricane activity in the Atlantic. That's because El Niño typically causes more vertical wind shear (the change in wind speed with height into the atmosphere) in the Atlantic, which typically breaks up big storms before they can form. However, NOAA is still predicting even odds on the formation of an El Niño weather pattern. That uncertainty means that the hurricane outlook is uncertain as well, Friedman said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another uncertainty is whether a 25- to 40-year weather pattern known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) has officially ended or not. For the past few decades, the Atlantic has seen stronger-than-usual hurricane activity, thanks to the AMO. However, the past three years saw weaker hurricane activity than prior years, which suggested the AMO could be phasing out.

The odds of a quiet season are low, however.

"The bottom line is, we're expecting a lot of activity this season. Whether that's near normal or above normal, that's a lot of hurricanes," Bell said in the briefing.

Be prepared

Whether it's a strong or a weak season, however, deadly hurricanes are always a risk, and people living on the East Coast should have their disaster plans in place. For instance, despite a relatively quiet season last year, Hurricane Matthew made landfall in South Carolina and caused about $10 billion in damages. And wind speed is imperfectly correlated with damage, Friedman added.

"The most dangerous part is not the wind and the rain; it's the flooding and the storm surge that happens afterward," Friedman said. "We need to be prepared for all of that."

Preparing for a hurricane is a matter of thinking ahead. Having an evacuation plan and a communications plan in place for times when the power is out; having a way to charge cellphones; checking in with neighbors who may need assistance; and having enough cash, food and first-aid supplies ready can also be helpful, said Robert Fenton, a regional administrator for the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Also, flood insurance is often not included in homeowners' insurance, and it often takes policies 30 days to kick into gear, so people should get approved for flood insurance now, before the hurricane season starts, Fenton added.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.