Mysterious Bison Hybrid Revealed from Ancient DNA and Cave Paintings

Clever detective work involving research on both ancient DNA and cave paintings from the last ice age has revealed a previously unknown species of hybrid bison, according to a new study.

Researchers initially nicknamed the newfound bison the "Higgs Bison," because, just like the once-elusive subatomic particle known as the Higgs Boson, the bison's very existence had never been confirmed, and it took about 15 years to piece together data that proved its existence.

But now, thanks to ancient DNA from the creatures' bones, researchers know that the mysterious bison was a hybrid animal that originated more than 120,000 years ago, when the extinct aurochs (the ancestor of modern cattle) and the ice-age steppe bison got together, the researchers said. [See Photos of the Cave Art That Helped Experts Crack the Bison Mystery]

Usually, hybrid animals aren't too successful, mainly because the males tend to be sterile, said the study's senior researcher Alan Cooper, director of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at the University of Adelaide in Australia. But the newfound hybrid bison did quite well for itself and its descendants, the modern-day European bison (Bison bonasus), which is also known as a wisent. The European bison are still alive today, he said.

The Aurochs (Bos primigenius) and bison (Bison priscus) are "genetically quite different," Cooper told Live Science. "[But they] produced something that was successful enough to carve out a niche on the landscape and go on to become, ironically, the biggest species [of other large animals] to survive the extinction at the end of the ice age in Europe."

In addition, the discovery of the hybrid shows that the steppe bison, which was once thought to be the only bison in that region during the last ice age, likely competed with the hybrid species for tens of thousands of years, Cooper said.

Hybrid mystery

To solve the animal's mysterious genetic background, an international team of researchers examined the creature's remains — that is, its bones and teeth — which were unearthed from caves in Europe, the Ural mountains in Russia and the Caucasus mountains in Eurasia.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then, the scientists studied ancient DNA from 64 different bison, including the creature's mitochondrial DNA (genetic material passed down through the mother's lineage) and nuclear DNA, or DNA passed down from both parents.

"We could see that the nuclear DNA was very obviously like the steppe bison," Cooper said. "The mitochondrial [was] telling us another [ancestor]: cattle."

The evidence suggested that the creature was a hybrid, likely started by a female Aurochs and a male steppe bison, he said. Moreover, the hybrid animal's nuclear DNA was about 90 percent steppe bison and 10 percent Aurochs, Cooper said.

"That ratio tells you that after the first hybridization event, there was back breeding with steppe bison for a little while, which is why the steppe bison DNA is higher," Cooper said. "That will often happen when you have a hybrid mammal, because the male [hybrid] offspring tend to be sterile." [Real or Fake? 8 Bizarre Hybrid Animals]

Cave paintings

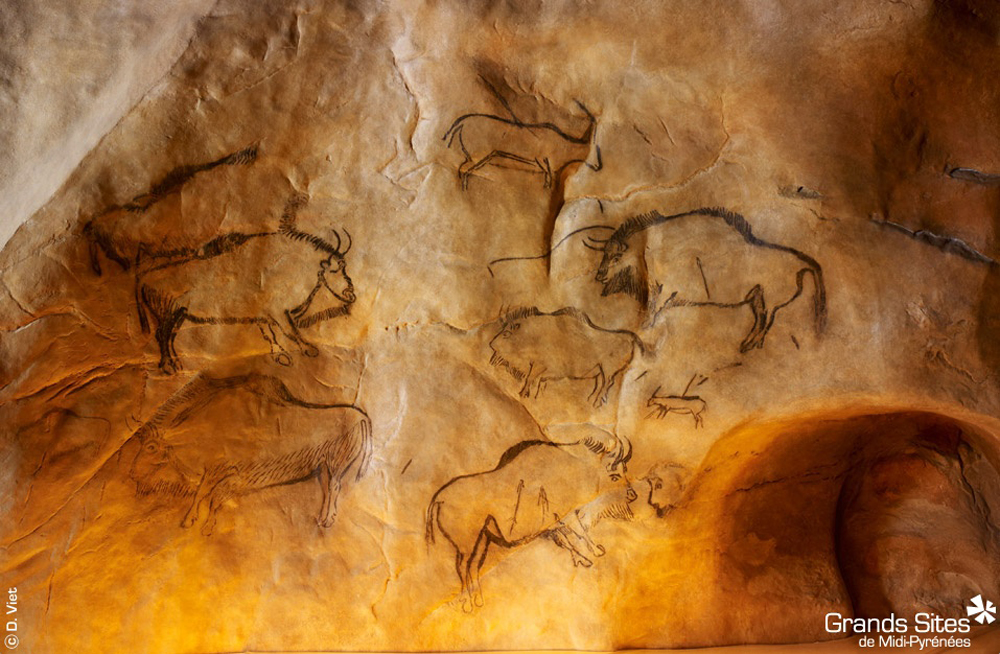

However, the researchers have yet to find a hybrid skull, meaning they can't truly assess what it looked like and what it ate. One day, one of Cooper's colleagues suggested that he look at the ice-age cave art that covers the walls of caves throughout Europe.

That advice changed the trajectory of the entire project.

"We contacted some French scientists who work on the cave art and asked them, 'Have you ever noticed anything funny about the bison? Because we have [discovered] a second species," Cooper recalled. "They said, 'Ah, at last! Someone finally believes us. We've been telling our colleagues for years that there are two forms of bison in the cave,' which had been previously explained as artistic or cultural or stylistic differences."

One form depicted a bison with either long horns or large forequarters, much like the American bison, which is descended from the steppe bison. In contrast, the other form had shorter horns and small humps, much like the modern European bison, Cooper said.

In an unexpected turn, the dates of the drawings, some of them 18,000 years old, matched the ages of the radiocarbon-dated bison bones, the researchers added.

"The dated bones revealed that our new species and the steppe bison swapped dominance in Europe several times, in concert with major environmental changes caused by climate change," study lead author Julien Soubrier, a postdoctoral research associate in the genetics and evolution unit at the University of Adelaide, said in a statement.

In other words, ancient people drew the hybrid bison when it was thriving during colder, tundra-like periods without warm summers, and they drew the steppe bison when it thrived during different climates (which have yet to be determined), Cooper said.

The hybrid bison's descendant, the modern European bison, suddenly appears in the fossil record about 11,700 years ago, just after the steppe bison went extinct. In fact, the modern bison nearly went extinct during World War I, when just 12 individuals survived in the wild. Given that all of today's modern bison are descended from these 12 individuals, they look genetically different from the hybrid bison, even though they're likely the descendants of them, Cooper said.

The study was published online today (Oct. 18) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.