Mudskipper Robot Mimics Ancient Land Animals' First 'Steps'

A robot modeled after the mudskipper fish that "walks" short distances over rocks and mud is helping scientists understand how animals moved millions of years ago, when they first emerged from the water and transitioned to walk on land.

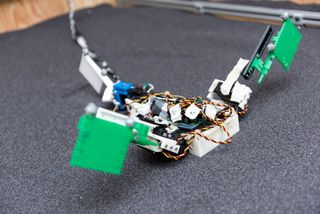

Observations of the African mudskipper helped scientists create the mechanical "MuddyBot," which wriggles over sand using limbs that resemble a mudskipper's powerful fins and tail.

A muscular tail in the earliest land animals may have played a more important role in their locomotion than previously thought. In a new study, researchers found that while fin "walking" is an effective way for the mudskipper and MuddyBot to scooch across flat surfaces, an undulating push from a tail is helpful for ascending sandy slopes. [Video: Unusual Fish that Can Walk & Breathe Hold Clues to Animal Evolution]

Animals that walk on land today evolved when early tetrapods — creatures with backbones and four limbs — shifted from their aquatic environments hundreds of millions of years ago. In the process, their limbs adapted to the new challenges of supporting and propelling their body weight over rocks, mud and sand.

And differences in the surfaces these tetrapods likely faced inspired scientists to investigate how that could have affected the way these ancient creatures moved.

An uphill climb

Mudskippers are known for their ability to navigate outside of the water using their fins as makeshift "legs." The researchers observed how mudskippers travel over loosely packed sand, and found that if they increase the slope of the granular surface, the mudskippers' fins become less effective; they instead rely more on their tails for momentum, and to prevent themselves from slipping downhill.

To further explore how an early tetrapod may have navigated on land, a team of biologists and engineers collaborated to build MuddyBot. They modeled it after the mudskipper's body plan, giving it two forelimbs and a tail appendage so it could mimic the fish's physical capabilities as a "walker."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the mudskipper is a living model of how early land animals may have moved, MuddyBot allows the scientists to vary the parameters of its movements, to better understand the motions of the different limbs, and to observe how they work relative to each other.

Much like the animal that inspired its design, MuddyBot also had difficulty ascending slopes using only its forelimbs, and could climb successfully only with a boost from its "tail," the study authors found.

The earliest land animals would have likely taken some of their first steps on sandy, sloping beaches, the researchers said. Their observations of mudskippers and the tests with MuddyBot suggest that primitive tetrapods would also have needed to propel themselves with their tails.

This clue to early locomotion has been "hiding in plain sight," according to study co-author Richard Blob, a professor of biological sciences at Clemson University in South Carolina. Blob said in a statement that the role of the tail in land locomotion — largely overlooked until now — may have been an important factor as animals transitioned to life out of water, an existing feature that helped to propel them into their strange, new habitat.

The findings were published online today (July 7) in the journal Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular