A network of ancient rivers lies frozen in time beneath one of Greenland's largest glaciers, new research reveals.

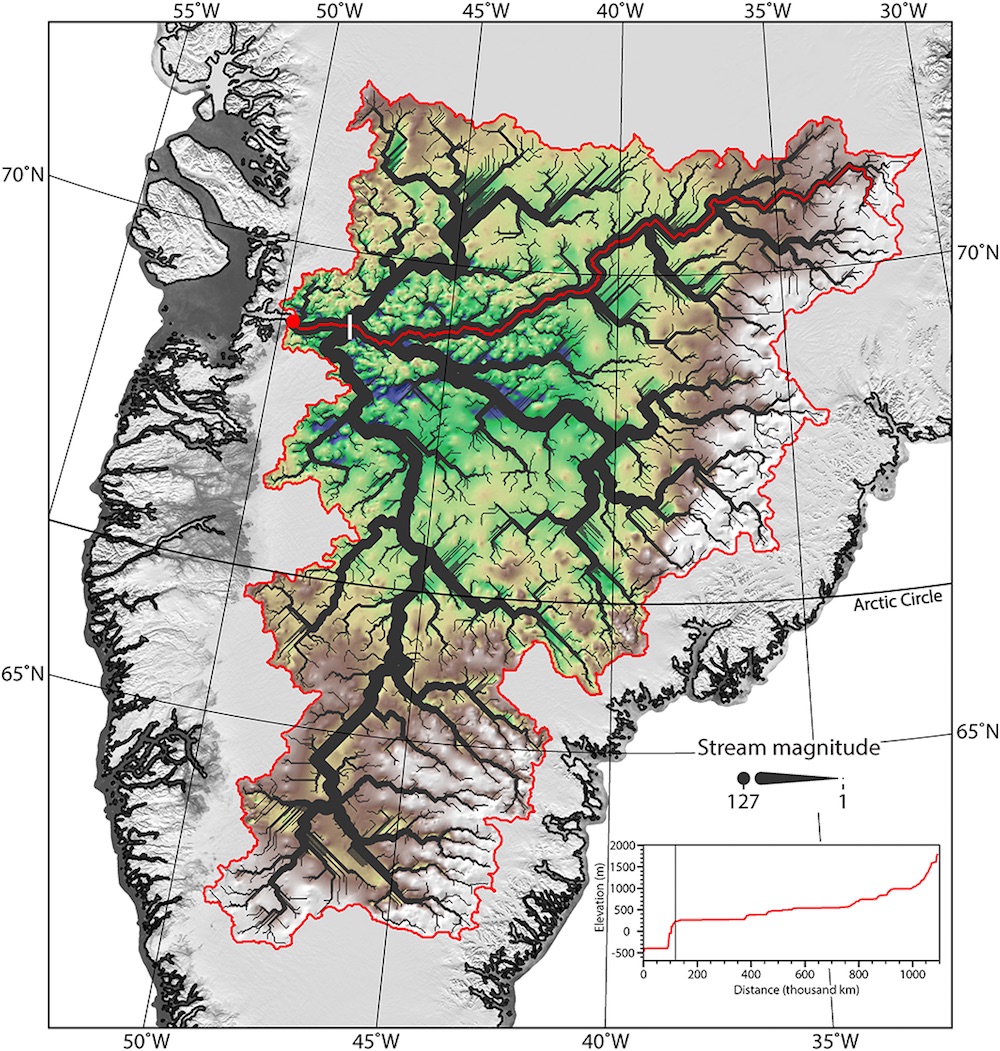

The subglacial river network, which threads through much of Greenland's landmass and looks, from above, like the tiny nerve fibers radiating from a brain cell, may have influenced the fast-moving Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier over the past few million years.

"The channels seem to be instrumental in controlling the location and form of the Jakobshavn ice stream — and seem to show a clear influence on the onset of fast flow in this region," study co-author Michael Cooper, a doctoral candidate in geography at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom, told Live Science. "Without the channels present underneath, the glacier may not exist in its current location or orientation." [See Images of Greenland's Gorgeous Glaciers]

Fast-moving glacier

The Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier in Greenland is the world's fastest glacier; it races toward the sea at the breakneck pace of 11 miles (17 kilometers) per year. The speedy glacier is dumping huge amounts of ice into the sea and is Greenland's main contributor to sea level rise, raising levels about 1 millimeter (0.04 inches) between 2000 and 2010, researchers previously told Live Science.

Climate scientists have zeroed in on this fast-moving glacier in recent years because it may be a harbinger of climate change to come. It is melting quickly: The glacier has lost more than 9,000 gigatons of ice since 1900, according to a 2015 study in the journal Nature.

A secret world, locked in ice

As part of the effort to characterize Jakobshavn, Cooper and his colleagues used ice-penetrating radar to peer beneath the massive hunk of ice and analyze the height of the bedrock below.

The radar revealed a secret world, frozen in ice. Beneath Jakobshavn lies a stunning landscape of jaw-dropping canyons, some of which are roughly the size of the Grand Canyon; dramatic ravines; and a lacework of mountain streams. By analyzing the shape of the valleys and canyons beneath the ice, the team determined that these features were likely formed by rivers cutting the rock away over time, rather than by the glacier.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The shape of the valleys was V-shaped, rather than U-shaped; the flow network had a dendritic or tree-like structure; and the long profiles showed a smooth, concave-up shape," Cooper told Live Science. These are good clues that the channel system was carved by rivers, not glaciers, he added.

Thus, the landscape must have formed at least 3.5 million years ago, prior to the ice sheet's formation. At that time, the area may have been much warmer and home to forests and shrubland, Cooper said.

"I imagine the landscape would have been home to a lot of life," Cooper said.

The glacier has had two effects. Near the interior, where the ice is the thickest, it has preserved the primeval landscape. At the edges, glacial ice has deepened some of the canyons through erosion, Cooper said.

The network of rivers that lies beneath the ice is now mostly dry, but some water does still flow.

"Near the margins, toward the outlet glacier, Jakobshavn Isbrae, the channels may well have water flowing through, as part of the modern-day subglacial drainage system," meaning water is seeping from the ice's surface to the bottom of the glacier, flowing along the edges of the ice-sheet bottom, he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.