Dodo Birds Weren't 'Dodos' After All

Dodos weren't as dumb as their reputation suggests. New research finds that these extinct, flightless birds were likely as smart as modern pigeons, and had a better sense of smell.

Dodos (Raphus cucullatus) had gone extinct by 1662, less than 100 years after their island home of Mauritius became a destination for Dutch explorers. The birds, unfamiliar with humans, were initially fearless. This made them easy pickings for hunters and also cemented their reputation as dullards.

A new computed tomography (CT) scan of a rare, intact dodo skull reveals that these birds had brain-to-body sizes that are similar to those of modern pigeons. [In Photos: The Famous Flightless Dodo]

"It’s not impressively large or impressively small — it's exactly the size you would predict it to be for its body size,” study researcher Eugenia Gold of Stony Brook University said in a statement, referring to the dodo's brain. “So if you take brain size as a proxy for intelligence, dodos probably had a similar intelligence level to pigeons."

And pigeons aren't that dumb. Studies find that they're capable of recognizing and remembering human faces. They're also very trainable and have mathematical abilities similar to those of rhesus monkeys.

Gold, an anatomist, was interested in learning more about the dodo's ecology, as this bird is mostly known through the contemporaneous accounts of the sailors and settlers who brought about the animal's demise. A few living dodos were brought back to Europe, she and her colleagues wrote today (Feb. 23) in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. But those animals were kept confined and fed human food, making them fat. Wild dodos may not have looked like the portly birds seen in European illustrations.

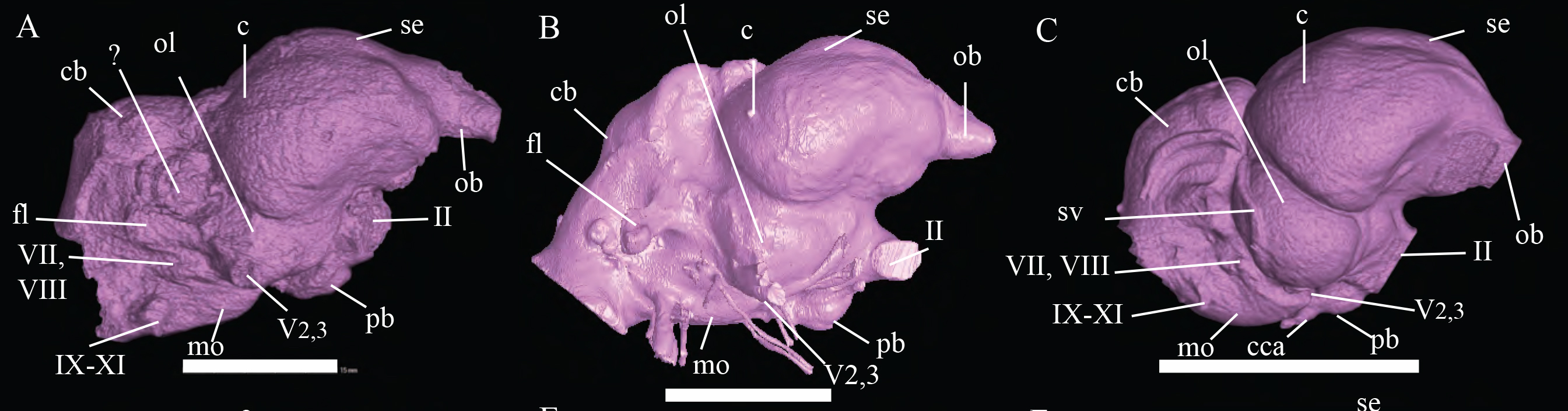

Gold and her colleagues conducted a CT scan of the dodo skull, which was at the Natural History Museum, London. They also scanned the skull of the dodo's closest relative, the Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria). This flightless bird lived on the Indian Ocean island of Rodrigues and went extinct in the 1700s, due to overhunting and other human activities. Using the scans, the researchers then reconstructed virtual "casts" of the bird brains.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scans showed a brain that compared with the body-to-brain ratio of modern pigeons. Unusually, the olfactory bulb of the brain, responsible for processing smells, was particularly large. Dodos, with their diet of fruit, shellfish and small land animals, might have relied heavily on smell for finding food, Gold and her colleagues wrote. In comparison, birds that fly tend to have smaller olfactory bulbs and larger optic bulbs, because they depend more on sight to navigate and to find prey.

Another odd feature was an extreme bend in one of the dodo's semicircular canals. These inner-ear organs are responsible for balance; it's possible, the researchers wrote, that the unique bend was simply a quirk of variability, the result of the semicircular canals being less crucial to a flightless bird than to its flying relatives. But to test that idea, researchers would need to study the semicircular canals of many dodos.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.