Rabies Vaccine Fails in Rare Death

The rabies vaccine unexpectedly failed to save the life of a 6-year-old boy in Tunisia who was infected with the deadly virus, even though doctors started treating him the same day a stray dog bit him on the face, according to a new report of his case.

"It's very rare to have the rabies post-exposure regimen fail, but there are cases where it does fail," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a member of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and a doctor at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, who was not involved in the child's care.

The vaccine almost always works when the injections are delivered soon after a person is exposed to the rabies virus. It's possible that the doctors failed to completely clean the dog's saliva from all of the boy's wounds. But even without such an error, there are rare instances in which the vaccine does not work in people, according to the case report, published Jan. 14 in the journal BMJ Case Reports.

After the dog bite, doctors immediately cleaned and treated the child's wounds, according to the case report. They administered rabies immunoglobulin, which are antibodies that can fight the rabies virus; these were delivered both directly to the bite wound on his forehead as well as intravenously, into his bloodstream. They also injected the post-exposure rabies vaccine into his arm on the day it happened and on days 3, 7 and 14 after the bite, following World Health Organization guidelines.

But 17 days after the dog bite, the child came to the hospital with fever, vomiting, pink eye and signs of neurological problems, including crossed eyes, agitation, uncoordinated muscle movements and brisk reflexes in his legs. He died that day after developing seizures and going into cardiac arrest. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

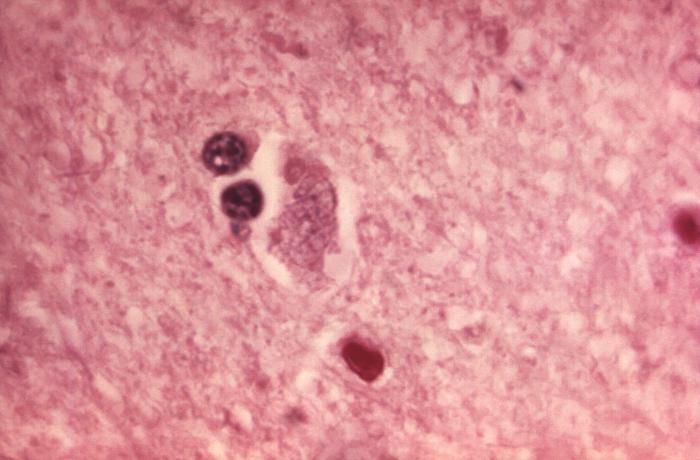

A later examination of the boy's brain found that he had rabies, the researchers wrote in the report. Other tests showed that the dog that bit him also had rabies.

The virus that causes rabies travels along nerve cells until it reaches the brain, where it causes fatal swelling. Bites from rabid dogs cause more than 98 percent of the 40,000 to 60,000 cases of rabies among people that occur every year worldwide, the researchers said. Tunisia, in northern Africa, has one to two human rabies deaths a year, typically from people who do not seek treatment after being bitten by dogs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Failure of the rabies vaccine is rare. In 1997, researchers reported at a conference that out of 15 million cases in which the vaccine had been used to date, it had failed in just 47 people, said Dr. Natasha Crowcroft, the chief of infectious diseases at Public Health Ontario, who was not involved with the care of the child in the recent case.

When the vaccine does fail, it's not unusual for people to have been bitten on the hand or face, parts of the body that have a high concentration of nerves that the rabies virus can potentially infect. Moreover, the virus doesn't have to travel far to the brain if it enters through a wound on the face, Crowcroft said.

Usually, "the rabies virus travels quite slowly to the brain up through the nerves," she said. "When we give the vaccine, it's a race of [the body] making antibodies from the vaccine and the virus traveling up to brain. As soon as the virus gets to the brain, it's too late."

The boy did not have hydrophobia (fear of water) or excessive salivation, two common rabies symptoms, when he returned to the hospital on day 17. "These features made the diagnosis of rabies encephalitis [swelling of the brain from rabies] difficult, especially in this child, who had received four doses of rabies vaccine” and other treatments, the researchers wrote in the case report.

It's possible that the doctors missed a wound that was infected when they examined the child, and therefore didn't properly clean and treat it with immunoglobulin, according to the case report. The doctors sutured the bite wound after cleaning and treating it, but if they missed some of the saliva, the suturing may have even helped the virus enter the nerves in the face, the researchers said.

Vaccines can also fail if they're expired or not stored at adequate temperatures, but that didn't happen in this case, the researchers said.

There is a pre-exposure rabies vaccine, but its high price makes it difficult to provide to people in developing countries, where many cases of rabies occur. Instead, only people who are at high risk of rabies, such as veterinarians, are usually given the pre-exposure vaccine, the researchers said.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.