How to Cool Buildings Without Electricity? Beam Heat into Space

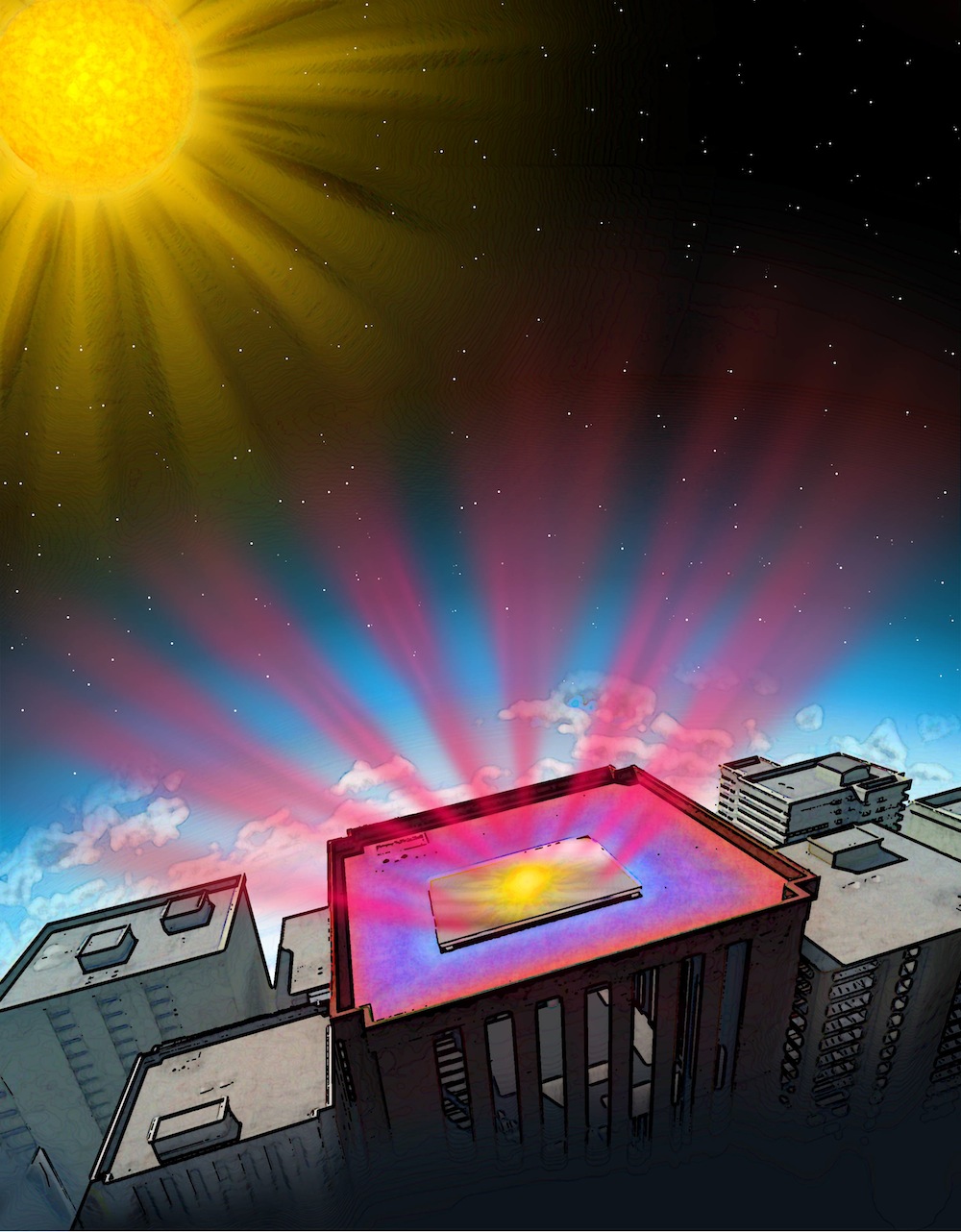

A new superthin material can cool buildings without requiring electricity, by beaming heat directly into outer space, researchers say.

In addition to cooling areas that don't have access to electrical power, the material could help reduce demand for electricity, since air conditioning accounts for nearly 15 percent of the electricity consumed by buildings in the United States.

The heart of the new cooler is a multilayered material measuring just 1.8 microns thick, which is thinner than the thinnest sheet of aluminum foil. In comparison, the average human hair is about 100 microns wide. [Top 10 Craziest Environmental Ideas]

This material is made of seven layers of silicon dioxide and hafnium dioxide on top of a thin layer of silver. The way each layer varies in thickness makes the material bend visible and invisible forms of light in ways that grant it cooling properties.

Invisible light in the form of infrared radiation is one key way all objects shed heat. "If you use an infrared camera, you can see we all glow in infrared light," said study co-author Shanhui Fan, an electrical engineer at Stanford University in California.

One way this material helps keep things cool is by serving as a highly effective mirror. By reflecting 97 percent of sunlight away, it helps keep anything it covers from heating up.

In addition, when this material does absorb heat, its composition and structure ensure that it only emits very specific wavelengths of infrared radiation, ones that air does not absorb, the researchers said. Instead, this infrared radiation is free to leave the atmosphere and head out into space.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The coldness of the universe is a vast resource that we can benefit from," Fan told Live Science.

The scientists tested a prototype of their cooler on a clear winter day in Stanford, California, and found it could cool to nearly 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) cooler than the surrounding air, even in the sunlight.

"This is very novel and an extraordinarily simple idea," Eli Yablonovitch, a photonics crystal expert at the University of California, Berkeley, who did not take part in this research, said in a statement.

The researchers suggested that their material's cost and performance compare favorably to those of other rooftop air-conditioning systems, such as those driven by electricity derived from solar cells. The new device could also work alongside these other technologies, the researchers said.

However, the scientists cautioned that their prototype measures only about 8 inches (20 centimeters) across, or about the size of a personal pizza. "We are now scaling production up to make larger samples," Fan said. "To cool buildings, you really need to cover large areas."

The scientists detailed their findings today (Nov. 26) in the journal Nature.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus