In May 2013, scientists from the Siberian Northeastern Federal University heard that mammoth tusks were sticking out of the permafrost on Maly Lyakhovsky Island in nothern Siberia. Researchers crossed miles of ice to see for themselves, and soon found the tusks belonged to a mammoth that had been exceptionally preserved beneath the permafrost. Mammoth experts performed a thorough autopsy on the animal, revealing intimate details of its life and grisly death. The carcass, which oozed fresh blood when it was first dislodged from the permafrost, is perhaps the best hope of cloning a mammoth yet. [Read the full story on the mammoth autopsy]

Frozen in time

When the team dug up the carcass, they found that almost all of the carcass was intact, with three legs, the majority of the body, part of the head and the trunk still present. The carcass also oozed a dark red liquid, which researchers hoped was blood. The carcass was so well preserved that a scientist took a bite of it. (Photo credit: Semyon Grigoriev/Northeastern Federal University in Yakutsk)

Mammoth autopsy

The scientists from Siberia soon realized what an exciting find they had. They convened a group of mammoth experts to conduct an autopsy on the extinct beast over a three-day period as the carcass thawed out. Carbon dating of the tissue revealed that the mammoth lived and died about 40,000 years ago. The team also recreated the mammoth's gruesome last moments: It was eaten alive by wolves and other predators after getting stuck in a peat bog. (Photo credit: Renegade Pictures)

Giant teeth

The team also analyzed the teeth of the ancient mammoth, which the teem nicknamed Buttercup. Because elephants typically replace their molars about six times in their lives, identifying which pair of molars the mammoth had, as well as studying the wear on those teeth, can reveal soemthing about the mammoth's age. In this case, the team determined that Buttercup was in her mid-50s when she died. (Photo credit: Renegade Pictures)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cold blood

When scientists conducted the autopsy, they managed to obtain a vial of blood from Buttercup. Though the blood cells are no longer intact, the sample still contains the oxygen-ferrying molecule hemoglobin. Mammoths had a special form of hemoglobin that still worked at near-freezing blood temperatures as blood flowed from the heart to their feet. Here, Roy Weber, a researcher at Aarhus University, Denmark, holds up a vial of Buttercup's blood. (Photo credit: Renegade Pictures)

Great tusks

Here, paleobiologist Tori Herridge of the Natural History Museum, London, poses with Buttercup's tusks. Herridge was one of the scientists involved with the mammoth autopsy. (Photo credit: Renegade Pictures)

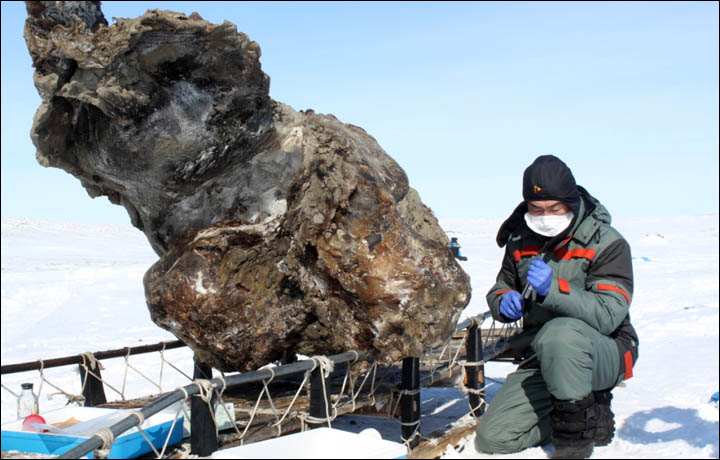

Cloned mammoth

The exceptionally preserved mammoth may be the best chance yet of cloning the extinct creatures. Here, cloning scientist Insung Hwang of SOOAM Biotech Research Center in South Korea, stands with the carcass. Despite its amazing preservation, finding enough intact DNA to completely recreate the genome of the mammoth is an incredibly difficult task, and so far, a complete genome has proved elusive. (Photo credit: Renegade Pictures)

Face to face

While the entire team hopes to find enough DNA to clone a mammoth from scratch, that could be tricky. For one, DNA is delicate and must be stored at cold, constant humidity in order to be preserved. Harvard University researcher George Church hopes to overcome those challenges one way or another. (Photo credit: Renegade Pictures)

Woolly elephant?

If an entire, intact mammoth genome can't be found from tissue in Buttercup's carcass, Church is investigating other ways to recreate the extinct behemoths. His team has developed a method for precisely targeting key snippets of mammoth DNA into the genome of the elephant. These modern-day hybrids would have the hair, tusks, blood and other characteristic features of a mammoth, though much of the genome would be the elephant's. (Photo credit: Renegade Pictures)

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.