Burnt Magna Carta Read for First Time in 283 Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

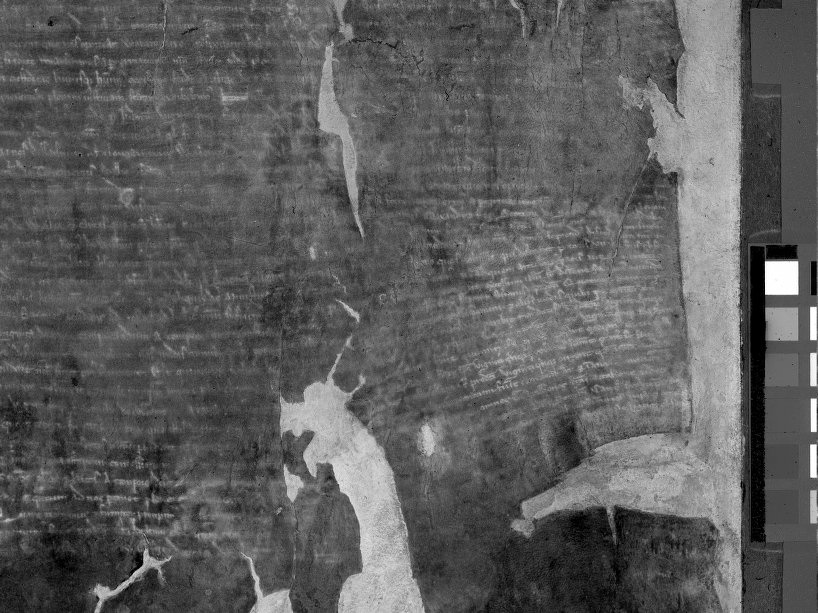

More than 280 years after it was damaged in a fire, one of the original copies of the Magna Carta is legible again.

Written in 1215, the Magna Carta required the king of England — King John — to cede absolute power. Today, the Magna Carta is seen as a first step toward constitutional law rather than the hereditary power of royalty. There were four copies of the document created at the time. One, held by the British Library, was badly damaged in a fire in 1731.

Now, researchers have used a technique called multispectral imaging to decipher the text of the "Burnt Magna Carta" without touching or further damaging the delicate parchment. This imaging allowed conservation scientists to take pictures of the document that virtually erase the damage and show details of the parchment and text.

"It was in such a terrible state, we couldn't read any of it, really," said Christina Duffy, a British Library imaging scientist. "It was actually quite a surprise that so much text was recovered." [See Images of the Recovered Magna Carta Text]

Damaged document

The imaging is part of the preparations for the 800th anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta, when King John imprinted his royal seal on the document and was bound by oath to abide by its demands. The British Library holds two of the original copies of the Magna Carta from 1215, including the burnt version. The other two copies are held at Lincoln Cathedral and Salisbury Cathedral.

On Feb. 3, 2015, the four copies will be displayed side-by-side at the British Library in London for the first time ever. The public can enter a lottery for free tickets to the viewing, which will be available to 1,215 winners. Registration is available on the British Library website.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Burnt Magna Carta has not been examined for decades, Duffy told Live Science. In the 1970s, it was set in a very secure frame, she said. That out-of-date frame has been removed in anticipation of the February 2015 anniversary, giving scientists the chance to get a closer look at the document.

Revisiting the text

The British Library team had no interest in trying to restore the smoke-damaged document, Duffy said, but wanted to preserve it as-is.

"There are different ways you can treat it," she said. "But a lot of them would be wet processes, so you might have to dampen certain areas, and we don't want to introduce any moisture at all to the charter."

Instead, the scientists used multispectral imaging, essentially photographing the burnt parchment in a variety of LED lights, spanning the spectrum from ultraviolet to infrared — outside the range of human vision.

"If you're interested in the ink, the ultraviolet light gives you the best information. If you are interested in the actual texture of the parchment itself, the infrared would be better," Duffy said. "You end up with multiple images of essentially the same thing, but giving you different information."

In these images, text that is invisible to the naked eye is suddenly visible. The Burnt Magna Carta is basically identical in text to the other three copies from 1215, Duffy said. The team is still processing the multispectral imagery and will conduct the same process on other old documents related to the Magna Carta, she said. Both the British Library's original Magna Carta manuscripts will be displayed between March 13, 2015 and Sept. 1, 2015, in an exhibit called "Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus