Handcuffs, Bear-Traps and Spikes Lift the Lid on Some Unique Insect Sexual Habits (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Handcuffs, spikes and traps – you would think they were part of some bondage aficionado’s bedroom collection. But what are they doing in the insect world?

A new study I worked on sheds light on why some bushcrickets – usually gentle creatures – get pretty violent when it comes to sex, and in the process helps to settle a decades-old debate about their odd mating habits.

In just a few species of bushcrickets, scattered across the evolutionary tree, we found that males have evolved horrific-looking clasping devices near their genitals. They use them to hold females down for as long as possible after sex is done – that is, after they have transferred all their sperm. This results in long mating sessions, up to seven hours in some cases.

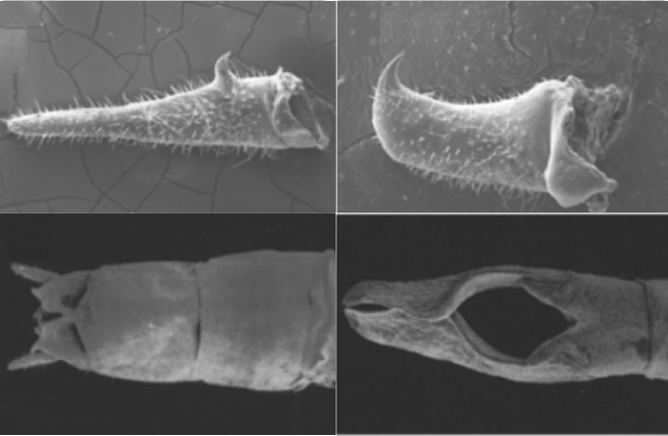

Bushcricket claspers are usually simple feelers that engage with pits on the female. But some species use spiked hooks to grab onto the female, often piercing her cuticle. Others have bear-traps, tongs that wrap around her, or even interlocking “handcuffs” that completely encircle her.

Females of these species are, perhaps understandably, not down with this. Although they themselves have not evolved any defensive tools, they actively resist by jumping, biting and kicking to dislodge the male – and with a degree of success, because species where females resist have less prolonged copulations than those where they do not.

Why would these males want to restrain their partners, when bushcrickets mating is usually relatively peaceful? Female bushcrickets aren’t dangerous to males, unlike in some spiders where, before sex, males gas females or tie them up in silk to avoid being cannibalised. The answer takes us into one of evolution’s most important, but also most secretive, conflicts – the battle over what happens to sperm after mating – and also helps answer a longstanding question about some other odd sexual habits of bushcrickets.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sperm in a bag

The act of mating itself is only the beginning of a struggle to determine which male actually gets to fertilise the female’s eggs. One in which females play just as active a part as males.

For example, female water striders have a submarine hatch covering their genitals, utterly preventing access. Unwanted males resort to “blackmailing” them into opening this hatch by threatening to attract predators. Other female insects have labyrinth-like vaginas with tortuous twists and blind endings. Some females even actively scoop sperm out of the male.

In most land animals, however, we never actually get to see what happens next, because sperm is placed deep inside the female. Often we have to make guesses about what male and females do with their genitalia, based on their shape. But bushcrickets are ideal study animals to look at the evolutionary fate of sperm.

Male bushcrickets transfer all their sperm in a bag, which then drip-feeds into the female after the male has left. But female bushcrickets can, if they want to, get rid of unwanted males’ sperm by simply removing (and usually eating) the sperm bag before the sperm is completely transferred. Males would naturally rather this didn’t happen, and try to stop it. And because this happens outside the female’s body, we have an opportunity to watch what is going on.

The food of love?

If giving females sperm in a drip-feed bag isn’t weird enough, male bushcrickets normally also produce a giant sticky blob of gel from their genitals, which females proceed to eat. This “nuptial gift” is enormously costly to produce, weighing up to 40% of the male’s body weight.

(To be fair, it could be substantially worse for the male – in sagebrush crickets, for instance, females suck the males' blood during sex and in striped ground crickets they begin eating his legs.)

For decades, scientists have debated what this huge nuptial gift, or “spermatophylax”, is for. Some think that the gift is a nutritious meal that helps the female make more, better babies with the male sperm – a win-win situation that is common in the insect world. Especially when food is scarce, females can use the gift as nutrition for making offspring.

But others think that the nuptial gift is also a device for manipulation – ensuring the female is distracted, so the sperm bag gets to drain as much sperm as possible before she gets around to eating it. Gifts contain very poor nutrition – the equivalent of flavoured chewing gum – and are laced with substances that stimulate the female to feed and also make her less likely to mate again afterwards.

Why bushcrickets get kinky

Our new study looks at some of the more bizarre mating habits of 44 species of bushcrickets to work out why in some cases males have resorted to more aggressive practices.

In a scattering of bushcricket species, we found that, over evolutionary time, males have stopped bothering to produce the nuptial gift for females at all.

In every case where the nuptial gift has been lost, males have evolved to protract sex for long periods even after they have transferred their sperm bag, attempting to restrain the female using hooks, tongs or handcuffs while she desperately resists. In cases where males present females with a food gift, though, the decision appears to be more mutual: females do not typically resist sex, and the males’ genital claspers fit neatly into special grooves on the female with no evidence for conflict.

Why do males of these species engage in such violent behaviour? We argue this almost certainly acts to prolong the drainage of sperm from the bag into the female for longer than she wants – the exact same function that had been proposed for the nuptial gift these species have lost. It is highly likely that this restraining behaviour is a substitute for the nuptial gift.

It’s what you do with it that counts

A great many studies of sexual conflict, especially spanning lots of species, focus on the form and complexity of male genital structures in particular – and there are certainly some corkers about.

But our study shows that sexual conflicts don’t necessarily lead to more complex male genital structures. For example, bushcricket male claspers already had simple hooked “teeth” – which usually engage peacefully with pits on the female. Some of our “stingy” males, though, used these same teeth in a different way – holding the female forcefully, piercing her cuticle. Without observing the behaviour, this difference wouldn’t have been obvious.

There is also currently a prevailing view that females are passive or possibly even willing recipients of male attempts to manipulate them. Female genital structures are often not as varied as those of males, and some have pointed to this fact as evidence that there really is no conflict going on. But our study clearly shows that, in this case, females actively and effectively resisted males using simple behaviour – jumping, biting and kicking – and not with specially evolved structures.

Whether you have gin-trap shaped genitals, a giant gift of jelly, or relatively normal-looking sexual apparatus, it is not what you have but what you do with it that counts.

James Gilbert receives funding from the European Commission’s Seventh Framework Programme.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus