Brain Cells Make Some Mice Resilient to Stress

People respond to stressful life events in very different ways — some people are resilient and move forward, while others end up suffering from depression. Now, scientists may have found the brain cells responsible for the varying reactions to stress.

In the study, the researchers closely examined a group of neurons in the brains of mice as the animals faced highly stressful situations. For instance, the mice repeatedly received painful electric shocks in their feet, which mimicked the conditions they face under uncontrollable and inescapable stress. The animals were then allowed to escape the shocks, as a test to see which mice showed stress resilience and which ones had become helpless and depressed.

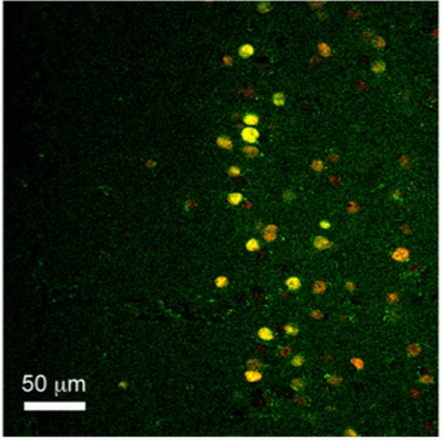

In the tests, about 22 percent of the mice displayed helpless, depressed behaviors: They often didn't try to escape the shocks even though they could. The researchers found that in these depressed mice, neurons in a brain region called the medial prefrontal cortex had become highly excited and active. [5 Ways Your Cells Deal With Stress]

The same neurons were weakened in the resilient mice that seemed unaffected by stress, according to the study, published today (May 27) in The Journal of Neuroscience.

The findings suggest that, at least in mice, higher activity in the medial prefrontal cortex is linked to poor behavioral responses to stress, and may underlie depression, the researchers said.

The findings are in line with previous studies in people that have found the prefrontal cortex is important in controlling behavior and coping with stress. Some studies have found this brain region is hyperactive in people with depression, a condition that is linked with stressful life events, the researchers said.

On the other hand, stress has been shown to alter both the structure and the functioning of brain cells in parts of the prefrontal cortex in humans, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To find out whether depression boosted activity in the medial prefrontal cortex or if the increased activity in that brain region led to depression, the researchers engineered mice to mimic the neuronal conditions they found in depressed mice.

"We artificially enhanced the activity of these neurons using a powerful method known as chemical genetics," said study researcher Bo Li, a neuroscientist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. "The results were remarkable: Once-strong and resilient mice became helpless, showing all of the classic signs of depression."

Although findings from animal studies don't necessarily apply directly to humans, the new findings may help researchers find a more precise target in an experimental treatment for depression, in which doctors use deep brain stimulation to control the activity of neurons in a specific area of the brain, the researchers said.

Next, to understand how depression develops, the researchers plan to explore the processes by which the neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex become hyperactive when responding to stress.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow us @LiveScience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.