'Mummy Lake' Used for Ancient Rituals, Not Water Storage

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

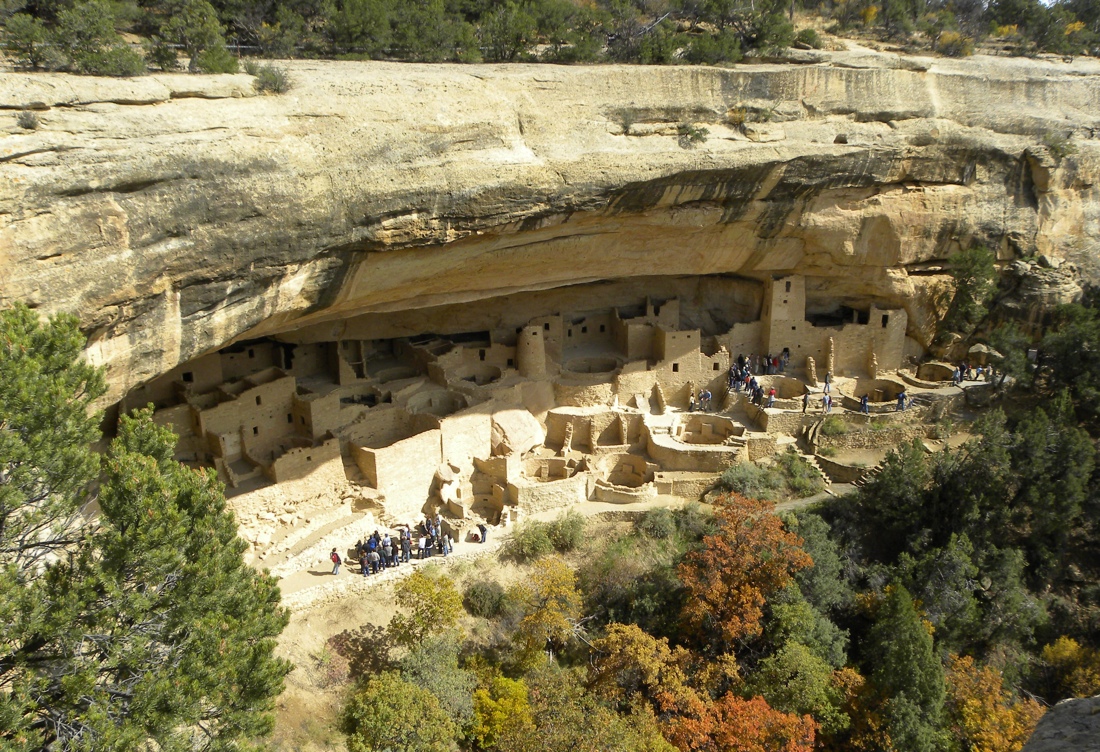

In Colorado's Mesa Verde National Park, a large 1,000-year-old structure long thought to be an Ancestral Puebloan water reservoir may not have been built to store water after all, a new study suggests.

Instead, the so-called Mummy Lake — which isn't a lake and has never been associated with mummies — likely held ancient ritual ceremonies, researchers say.

Mummy Lake is a sandstone-lined circular pit that was originally 90 feet (27.5 meters) across and 22 feet (6.65 m) deep. In 1917, American naturalist Jesse Walter Fewkes pegged the structure as a prehistoric water reservoir. Several subsequent studies of Mummy Lake have also supported this view, leading the National Parks Service to officially name the structure "Far View Reservoir" in 2006. (Far View refers to the group of archaeological structures located on the northern part of the park's Chapin Mesa ridge, where Mummy Lake is also situated.)

In the new study, researchers analyzed the hydrologic, topographic, climatic and sedimentary features of Mummy Lake and the surrounding cliff area. They concluded that, contrary to what previous research had determined, the pit wouldn't have effectively collected or distributed water. [See Images of Mummy Lake in Mesa Verde]

"The fundamental problem with Mummy Lake is that it's on a ridge," said study lead author Larry Benson, an emeritus research scientist for the U.S. Geological Survey and adjunct curator of anthropology at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History. "It's hard to believe that Native Americans who understood the landscape and were in need of water would have decided to build a reservoir on that ridge."

A supposed reservoir

Far View Village lies on a ridgeline that decreases in elevation from north to south, and includes Far View House, Pipe Shrine House, Far View Tower, Mummy Lake and other buildings. Previously, scientists had thought Mummy Lake — the northernmost structure — was a key part of a large water collection and distribution system that transported water between these structures to areas south of the reservoir.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They proposed that a gathering basin was once located uphill from Mummy Lake, and that a hypothetical "feeder ditch" connected the two locations. Studies have shown that another shallow, foot-paved ditch runs south from Mummy Lake to Far View House and Pipe Shrine House, and a third ditch connects Far View Village to Spruce Tree House and Cliff Palace (two structures built centuries after the Far View group) farther south. [Image Gallery: Lake Natron Gives Up Its Dead]

The prevailing idea was that precipitation would first collect in the basin, and then travel down to Mummy Lake along the ditch; from there, some of it could then travel to the rest of the village, providing water for drinking and irrigating crops.

"I think it's appealing to think of Mummy Lake as a reservoir," Benson told Live Science, noting that the Ancestral Puebloans of Mesa Verde lived in a region without any natural bodies of water. "[Scientists] naturally want to find structures that hold or convey water, to explain how the people got their water."

Testing the theory

To test this reservoir theory, Benson and his colleagues first analyzed the topography and hydrology of the ridge using GPS surveys, high-resolution imagery and digital elevation models.

They found that the ditches leading from Mummy Lake to the southern structures couldn't have functioned as water canals or irrigation distribution systems. The ditches would have easily spilled water over the canyon edge at various points if it didn't have walls controlling the water flow (which don't appear to have existed).

Next, the team used climate models to investigate Mummy Lake's potential to store water. They found that even in the wettest year on record, 1941, the pit would have gotten less than a foot of water from winter and spring precipitation by the end of April. This water would have completely evaporated by the end of July, when it's most needed for crops.

The researchers then tested if a hypothetical feeder ditch could actually provide Mummy Lake with water. "The engineering and sediment transport work showed that any water in the ditch would start moving so much dirt that it would block the path," Benson said. That is, soil would have quickly clogged the ditch after regular rainfall, preventing the water from reaching Mummy Lake.

A ceremonial structure?

Benson and his colleagues propose Mummy Lake is an unroofed ceremonial structure, not unlike the ancient kivas and plazas elsewhere in the Southwest. They noted that the structure is similar in size to a great kiva found at a Pueblohistorical site near Zuni, N.M. It also resembles a ball court and amphitheater at the Puebloan village of Wupatki in Arizona — interestingly, Fewkes also thought these two structures were reservoirs.

Furthermore, the ditches connecting Mummy Lake to Far View Village, Spruce Tree House and Cliff Palace aren't canals to transport water, but rather Chacoan ceremony roads with similar dimensions to Chacoan roads that exist at other sites in the San Juan Basin, the researchers argue.

Two decades ago, researchers studying the Manuelito Canyon Community of New Mexico discovered the Ancestral Puebloan population had an evolving ritual landscape. Over the centuries, the Manuelito people relocated the ritual focus of their community several times. Each time they moved, they built ceremonial roads to connect their retired great houses and great kivas to the new complexes.

Benson and his colleagues suspect the same thing happened at Mesa Verde. Mummy Lake was built as early as A.D. 900, around the same time as the rest of the Far View group of structures; Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House, on the other hand, date to the early 1200s. The researchers think the community relocated to the latter structures between A.D. 1225 and 1250, and connected their past with their present using the ceremonial roads.

If the Far View Reservoir really had nothing to do with water, then it may be time for another name change. "I think [the structure] needs new signage," Benson said. "We could probably call it 'Mummy Lake' again."

The study was detailed in the April issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Follow Joseph Castro on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus