300,000-Year-Old Caveman 'Campfire' Found in Israel

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

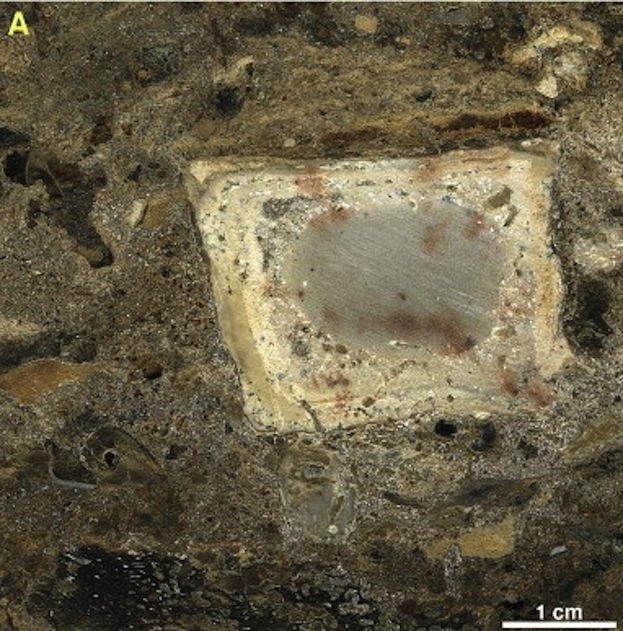

A newly discovered hearth full of ash and charred bone in a cave in modern-day Israel hints that early humans sat around fires as early as 300,000 years ago — before Homo sapiens arose in Africa.

In and around the hearth, archaeologists say they also found bits of stone tools that were likely used for butchering and cutting animals.

The finds could shed light on a turning point in the development of culture "in which humans first began to regularly use fire both for cooking meat and as a focal point — a sort of campfire — for social gatherings," said archaeologist Ruth Shahack-Gross of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. [10 Things that Make Humans Special]

"They also tell us something about the impressive levels of social and cognitive development of humans living some 300,000 years ago," Shahack-Gross added in a statement.

The centrally located fire pit is about 6.5 feet (2 meters) in diameter at its widest point, and its ash layers suggest the hearth was used repeatedly over time, according to the study, which was detailed in the Journal of Archaeological Science on Jan. 25. Shahack-Gross and colleagues think these features indicate the hearth may have been used by large groups of cave dwellers. What's more, its position implies some planning went into deciding where to put the fire pit, suggesting whoever built it must have had a certain level of intelligence.

Controversial cave

Qesem Cave was discovered more than a decade ago during the construction of a road some 7 miles (11 kilometers) east of Tel Aviv. At the site, excavators had previously uncovered other traces of fire (scattered deposits of ash and clumps of soil that had been heated to high temperatures) as well as the butchered bones of big game like deer, aurochs and horse left their by the prehistoric cave dwellers, possibly up to 400,000 years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Anthropologists have debated what constitutes the earliest evidence of controlled fire use — and which hominin species was responsible for it. Ash and burnt bone in Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa suggests human ancestors used fire at least 1 million years ago. Some researchers, meanwhile, have speculated that the teeth of Homo erectus suggest this early human was adapted to eat food cooked over a fire by 1.9 million years ago. A study out last year in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal argued that fire-builders would have needed some sophisticated abilities to keep their hearths burning, such as long-term planning (gathering firewood) and group cooperation.

It's not entirely clear who was cooking at Qesem Cave. A study published about three years ago in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology described teeth found in the cave dating to between 400,000 and 200,000 years ago. The authors speculated the teeth might have belonged to modern humans (Homo sapiens), Neanderthals or perhaps a different species, though they noted they couldn't draw a solid conclusion from their evidence.

Nonetheless, study researcher Avi Gopher, an archaeologist from Tel Aviv University, said in an interview with Nature at the time, "The best match for these teeth are those from the Skhul and Qafzeh caves in northern Israel, which date later [to between 80,000 and 120,000 years ago] and which are generally thought to be modern humans of sorts."

That interpretation is at odds with the predominant view that modern humans, the only human species alive today, originated about 200,000 years ago in Africa before dispersing to other parts of the world.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus