New Glue Could Mend Broken Hearts

In one episode of the TV show "Star Trek: The Next Generation," Captain Jean-Luc Picard is stabbed in the chest but survives thanks to a device that stitches up wounds in his heart. Now, real researchers have invented an adhesive that can also repair heart wounds.

The glue bonds to heart tissue, and is as strong as stitches or staples, sealing wounds while avoiding complications, say its inventors, Jeffrey M. Karp, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, andDr. Pedro del Nido, a cardiac surgeon at Boston Children's Hospital.

Staples and sutures (stitches) can cause problems. "With each pass of a suture needle, you have to realign the tissue," Karp said. "Staples can damage tissue, and they need to be bent to lock into place." In addition, staples don't provide a watertight seal, and are often metal, so they have to be removed, he said.

To solve these problems, the researchers aimed to design a water-repellent polymer glue that could harden quickly and create a seal that could withstand the stress in a beating heart or a blood vessel, according to the paper published today (Jan. 8) in the journal Science Translational Medicine. [Top 10 Amazing Facts About Your Heart]

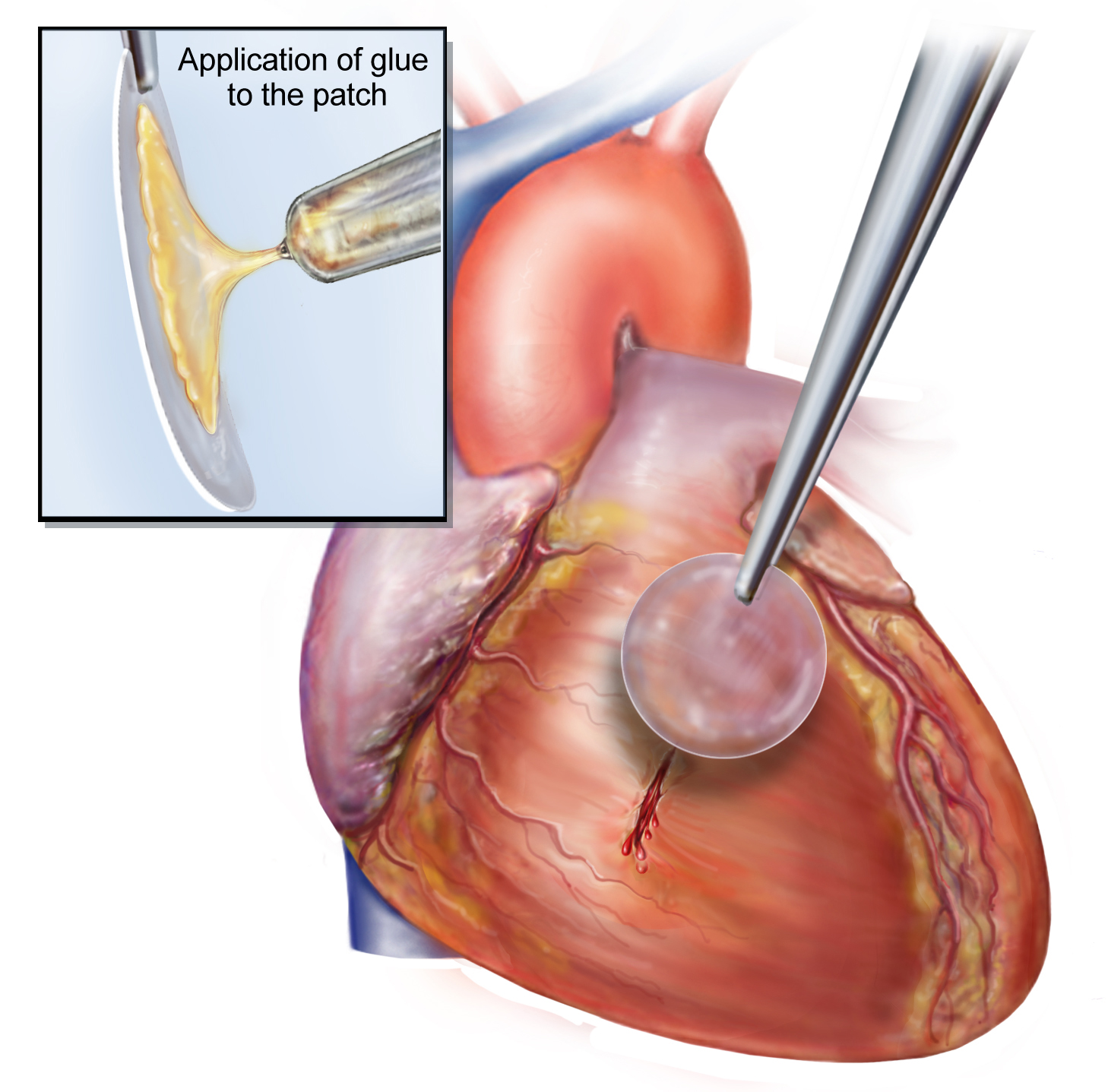

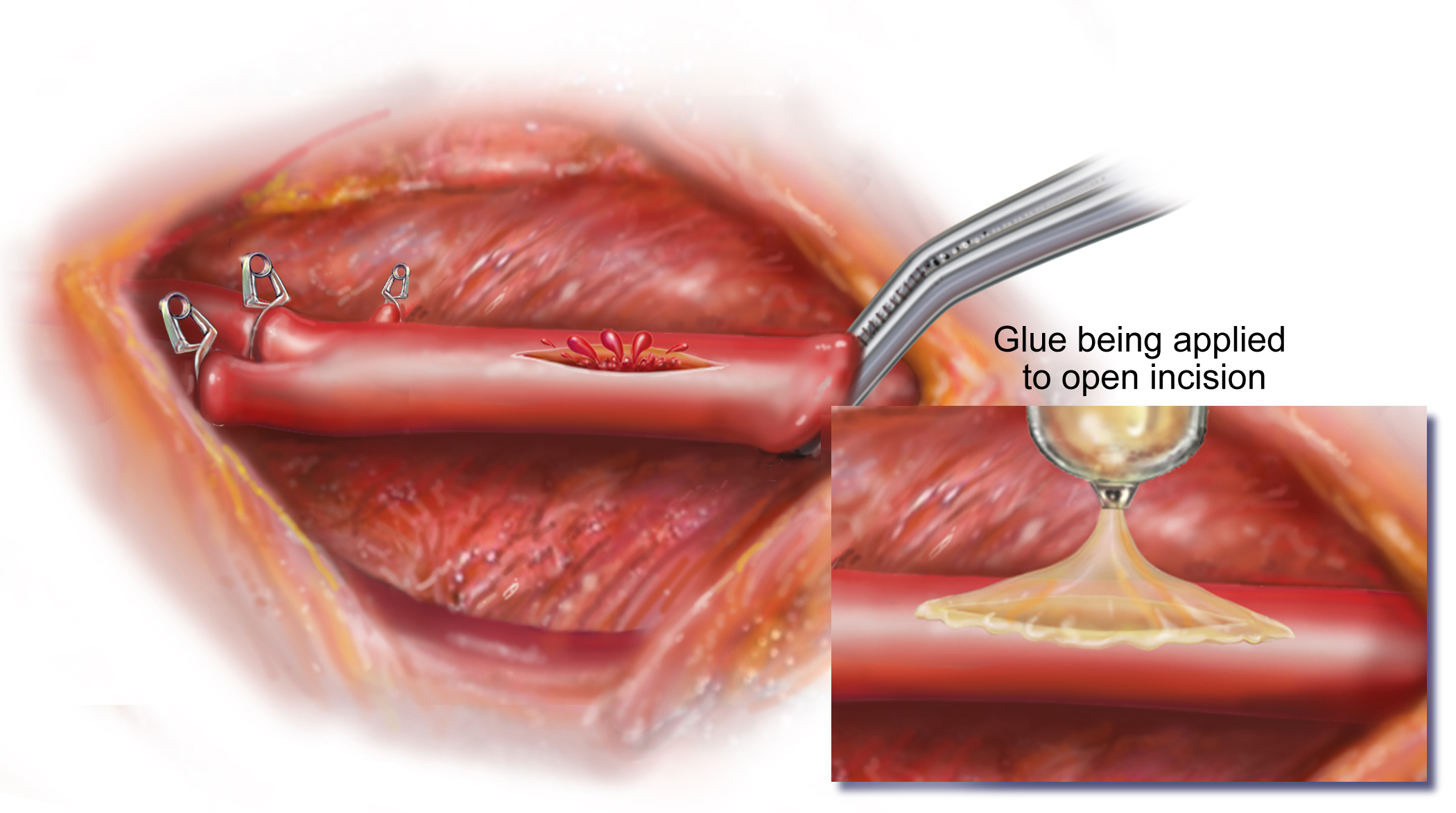

The glue starts off with the viscosity of honey. A doctor can paint it onto a patch, and use the patch on the heart to repair a hole in tissue (similar to what one might do on a bicycle tire). Or, a doctor could apply the glue directly to a tear in a blood vessel or intestinal wall, and clamp the edges of the torn tissue together until the glue hardens.

Once it is in place, the glue molecules work their way between the collagen fibers in the tissue. (Collagen is the protein that gives tissue its structure and shape.) The surgeon then shines ultraviolet light on the glue, causing the glue molecules to release free radicals, which are highly reactive and bind molecules in the glue called acrylate groups to one another, creating strong chains. The result is a substance that resembles rubber, with molecules that are intertwined with the heart's own collagen.

So far, the team has tested the glue on pigs and rats. In pigs, the researchers inserted a patch into a living heart, and attached it to the septum, which separates the left and right atria, the two upper chambers of the heart. They also repaired a coronary artery (which brings blood to the heart muscle) by cutting an incision in the artery and then applying the glue to the wound.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In rats, the researchers cut tiny holes in the animals' hearts, similar to what certain birth defects might cause, and then patched them with a piece of material that allowed the tissue to regrow and seal the hole.

While other wound adhesives exist, they don't seal as quickly as the new glue does, Karp said. Moreover, some of those adhesives require that the tissue be dried for the adhesive to stick, while others aren't compatible with certain types of tissue.

Human trials still need to be conducted before this glue can be used in the clinic. Karp and several others formed a company to market the glue, called Gecko Biomedical, which has raised about $10 million. The researchers said the company may get approval to use the glue in Europe by the end of 2015.

Karp said the glue might make some surgeries easier by eliminating the need for stitches. "One of the major limitations in adopting minimally invasive approaches in the clinic is that there are no suitable adhesives that can work in such a challenging environment" inside the body, he said.

Editor's note: This story was updated on Jan. 10 with a correction — the arteries that bring blood to the heart are the coronary arteries (not the carotid arteries).

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.