In Photos: China's Terracotta Warriors Inspired by Greek Art

Terracotta Warriors

About 8,000 Terracotta Warriors were buried in three pits less than a mile to the northeast of the mausoleum of the First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi. They include infantryman, archers, cavalry, charioteers and generals. Now new research, including newly translated ancient records, indicates that the construction of these warriors was inspired by Greek art.

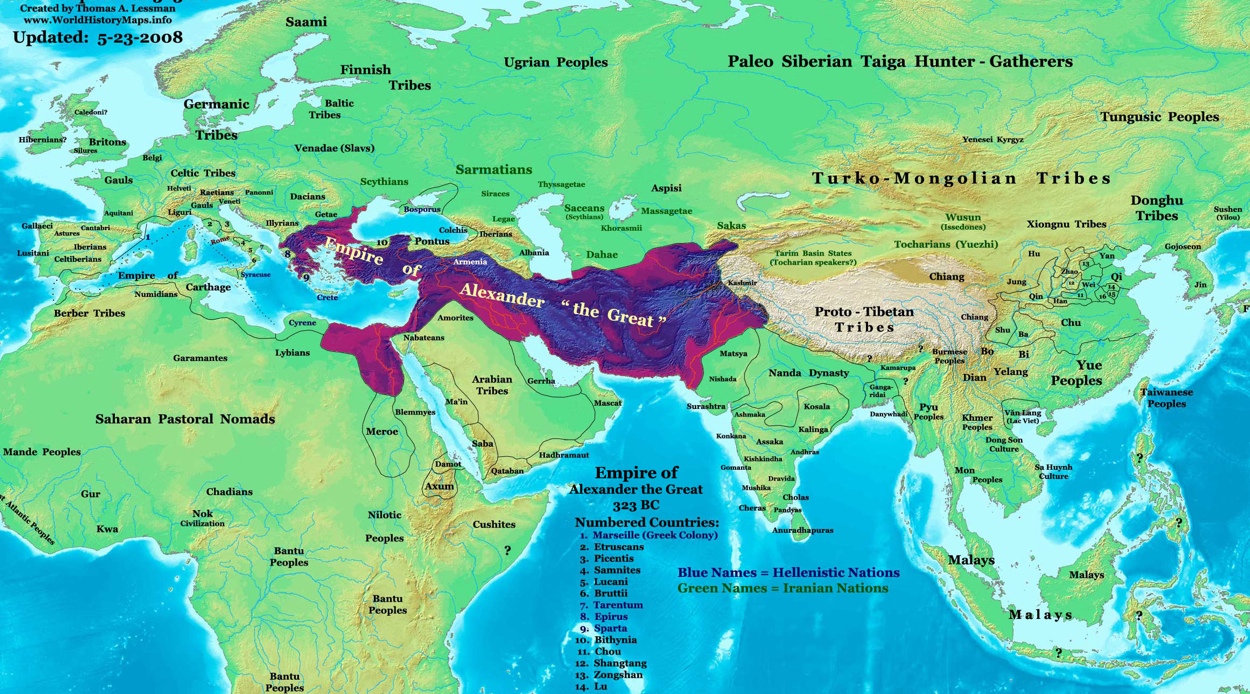

Alexander the Great map

By 323 B.C., about a century before Qin Shi Huangdi unified China, Alexander the Great had conquered an empire that stretched as far east as central Asia. In doing so he didn't just conquer territory but left behind Greek people, new cities and Greek cultural ideas. These people, cities and ideas remained after Alexander's death.

Alexander Statue

Among the ideas the Greeks brought east with them was that of building life-sized human sculpture. This particular work is of Alexander the Great himself, it dates from the third century B.C. and is now in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.

Terracotta Civil Official

Before the First Emperor of China came to power life-sized sculpture had never been used in China. Lukas Nickel, a reader with the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, argues in a newly published paper that this idea came from Greek-influenced kingdoms in central Asia. This image shows a Terracotta civil official.

Ban Gu

In his paper Nickel translated several Chinese records into English that tell of the "appearance" of 12 giant statues in Lintao, a town in western China. They are said to have stood 38 feet (11.55 meters) high, with feet 4.5 feet (1.38 meters) in size. The First Emperor was so impressed with them that he ordered the creation of duplicates to stand in front of his palace.

Unfortunately the statues no longer survive, having been destroyed in the centuries after the First Emperor's death. Nickel said that these records suggest contact, of some form, between China and Greek-influenced kingdoms in central Asia. Here, an imaginative illustration of Ban Gu, one of the historians who reported on the statues.

Terracotta Acrobat

In addition to the warriors a few dozen half-naked Terracotta dancers and acrobats have been found in pits near the First Emperor's mausoleum. Unlike the warriors these sculptures depict people in movement, something that Nickel points out the Greeks had mastered after generations of practice.

Han Dynasty miniature

Curiously the construction of full-sized sculpture stopped after the death of the First Emperor of China. The dynasty that succeeded him, known as the Han, instead created miniature figures of people, animals and objects, an example of which is shown here. Why the Han stopped building life-sized sculptures is a mystery, but one possibility is that they did not like the foreign influenced sculptures the First Emperor introduced.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

NYC Exhibition

Shown here, one of nine Terracotta Warriors that was on display at the Terracotta Warrior exhibition at New York City's Discovery Times Square in 2012. China lets only 10 of the warriors leave the country at any given time.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.