Oldest Human Tumor Found in Neanderthal Bone

The oldest human tumor ever found — by more than 100,000 years — has been discovered in the rib of a Neanderthal.

The bone, excavated more than 100 years ago in Croatia, has been hollowed out by a tumor still seen in humans today, known as fibrous dysplasia. These tumors are not cancerous (they don't spread to other tissues), but they replace the weblike inner structure of a bone with a soft, fibrous mass.

"They range all the way from being totally benign, where you wouldn’t recognize them, to being extremely painful," said David Frayer, an anthropologist at the University of Kansas who reported the finding along with his colleagues today (June 5) in the journal PLOS ONE. "The size of this one, and the bulging of it, probably caused the individual pain." [Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans]

Unusual bone

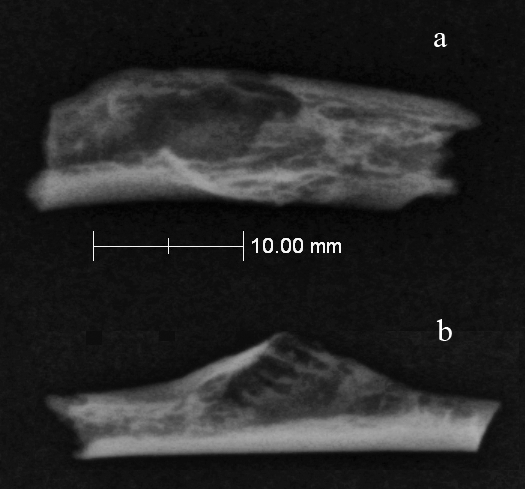

The Neanderthal rib fragment measures just more than an inch long (30 millimeters). It was first unearthed between 1899 and 1905 in a cave known as the Krapina rock shelter in Croatia. This site held more than 900 Neanderthal bones dating back 120,000 to 130,000 years ago. Many of the bones display signs of trauma, and quite a few show post-mortem cutting marks, perhaps indicating cannibalism or some sort of ritual reburial.

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) were a human species closely related to modern humans (Homo sapiens). They died out approximately 30,000 years ago, though not without apparently interbreeding with Homo sapiens: Many modern-day humans carry Neanderthal DNA, suggesting the two species had sex.

In the 1980s, University of Pennsylvania researchers X-rayed the entire collection of bones found at Krapina, and they published a book in 1999 showing each radiograph. Most of those X-rays were quite high-quality, said Janet Monge, the keeper of physical anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, who participated in that project and the current study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But there was one exception: One little rib fragment appeared "burned out" in the X-ray image, an overexposure that turned out to be due to the loss of inner bone in the specimen.

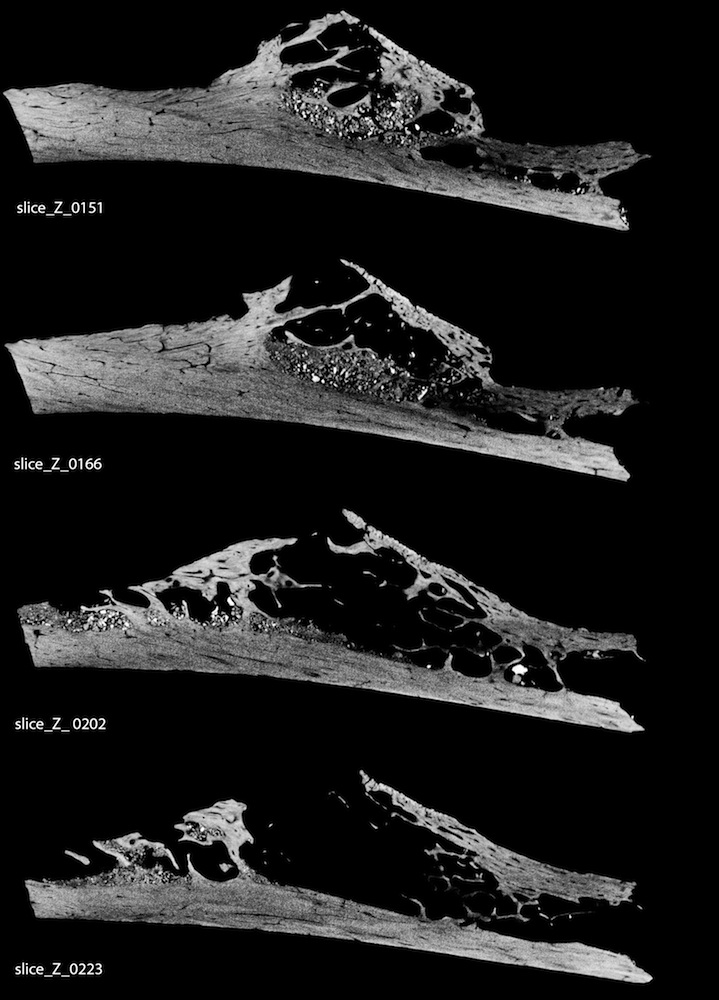

Now, the study researchers have returned to the rib, subjecting it to higher-quality X-rays and to microCT (computed tomography) scanning, which is similar to — but higher-resolution than — the types of scans doctors use to detect bone trauma in living patients.

Ancient tumor

The new images reveal a hollow shell, with an empty cavity where a network of inner "spongy bone" should be. (This spongy bone is so named because it's full of holes where blood vessels sneak through.)

"We do see it in human patients today," Monge told LiveScience. "It's exactly the same kind of process and in the same place."

Fibrous dysplasia is caused by a spontaneous genetic mutation in the cells that produce bone, according to the Mayo Clinic. In some cases, the tumors are small and asymptomatic. In other cases, they cause pain and weakness. Because the researchers have only an isolated rib from this particular Neanderthal, they can't say whether his or her other bones would have been affected.

Previously, the oldest known tumors came from Egyptian mummies and dated back only 4,000 years or so. (A 1,600-year-old tumor containing teeth was found in the pelvis of an ancient Roman corpse.) That makes the Neanderthal tumor, at about 120,000 years old, the most ancient "by a lot!" Monge said.

In many ways, the Neanderthal tumor is a needle-in-a-haystack find, Frayer said.

"People of that time didn't live as long as they did today; plus, there weren't very many of them compared to the Egyptians and people today," he told LiveScience. "So finding evidence of tumors and evidence of cancers, is — I don't know if I want to say ‘lucky’ — but there isn't a lot of evidence for it."

Anthropologists and archaeologists are always debating how similar Neanderthals were to Homo sapiens who lived in their era, sometimes alongside one another, Monge said. The new rib analysis reveals that, in at least one area, modern humans and Neanderthals had a lot in common.

"They lived their lives basically the same way we did and basically with the same problems that we have," Monge said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus