Teen Dinosaurs Got into Trouble

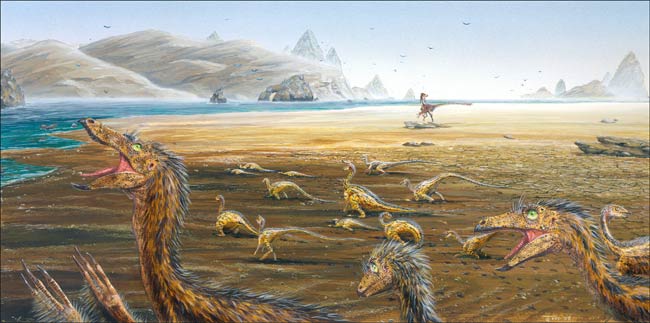

Like teenagers today, some juvenile dinosaurs used to hang out together, according to research announced today.

Also like teens, the dinos sometimes hung out in places they shouldn't have.

The evidence comes from of a herd of young birdlike dinosaurs that died when they became mired in mud on the margins of a lake about 90 million years ago, according to a team of paleontologists that excavated the remains in the Gobi Desert in western Inner Mongolia.

The sudden death of the herd in a mud trap provides a rare snapshot of social behavior in dinosaurs. Composed entirely of juveniles of a single species of ornithomimid dinosaur (Sinornithomimus dongi), the herd suggests that immature individuals were left to fend for themselves when adults were preoccupied, perhaps with nesting or brooding.

"There were no adults or hatchlings," said University of Chicago paleontologist Paul Sereno.

Within an exquisite pair of the skeletons, prepared for display in Sereno's lab and airlifted back to China in late February, stomach stones and the animals' last meals are preserved.

Sinornithomimus and other ornithomimids were theropod dinosaurs, the group that includes tyrannosaurs, but unlike most theropods, ornithomimids were herbivores, research shows. They also were small, big-eyed, fast and resembled ostriches in some ways.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rare, mired herds

Sereno, Tan Lin of the Department of Land and Resources of Inner Mongolia, and Zhao Xijin, professor in the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, led the 2001 expedition that found the fossils. Team members also included paleontologist David Varricchio of Montana State University (MSU), Jeffrey Wilson of the University of Michigan and Gabrielle Lyon of Project Exploration. The findings are detailed in the December 2008 issue of the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, and the work was funded by the National Geographic Society and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

"Finding a mired herd is exceedingly rare among living animals," Varricchio said. "The best examples are from hoofed mammals," such as water buffalo in Australia or feral horses in the American West, he said.

Other herds, consisting mainly or entirely of juveniles, have been found in the following dinosaur groups: sauropods, theropods, ankylosaurs, ceratopsians and ornithopods. Although modern birds evolved from dinosaurs, there is little herding or flocking of juveniles found among living birds. Similarly, juveniles tend not to herd together among other land-based vertebrates living today — with humans being one big exception, along with common ravens and ostriches. Along with adults being preoccupied, juvenile herding is favored among dinosaurs perhaps because it takes them many years to achieve sexual maturity, Sereno and his colleagues wrote.

More than 25 individuals

The first bones from the dinosaur herd were spotted by a Chinese geologist in 1978 at the base of a small hill in a desolate, windswept region of the Gobi Desert. Some 20 years later, a Sino-Japanese team excavated the first skeletons, naming the dinosaur Sinornithomimus ("Chinese bird mimic").

Sereno and associates then opened an expansive quarry, following one skeleton after another deep into the base of the hill. In sum, more than 25 individuals were excavated from the site. They range in age from 1 to 7 years, as determined by the annual growth rings in their bones.

The team recorded the position of all of the bones and the details of the rock layers to try to understand how so many animals of the same species perished in one place. The skeletons showed similar exquisite preservation and were mostly facing the same direction, suggesting that they died together and over a short interval.

A slow death

The details provided key evidence of an ancient tragedy. Two of the skeletons fell one right over the other. Although most of their skeletons lay on a flat horizontal plane, their hind legs were stuck deeply in the mud below. Only their hip bones were missing, which was likely the handiwork of a scavenger working over the meatiest part of the body bodies shortly after the animals died.

"These animals died a slow death in a mud trap. Their flailing only serving to attract a nearby scavenger or predator," Sereno said. Usually, weathering, scavenging or transport of bone have long erased all direct evidence of the cause of death. The site provides some of the best evidence to date of the cause of death of a dinosaur.

Plunging marks in mud surrounding the skeletons recorded their failed attempts to escape. Varricchio said he was both excited and saddened by what the excavation revealed. "I was saddened because I knew how the animals had perished. It was a strange sensation and the only time I had felt that way at a dig," he said.

In addition to herd composition and behavior, the site also provides encyclopedic knowledge of even the tiniest bones in the skull and skeleton.

"We even know the size of its eyeball," Sereno said. "Sinornithomimus is destined to become one of the best-understood dinosaurs in the world."

- Video: A Meal with the 'Leonardo' Dino

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs

- Gallery: Drawing Dinosaurs