50th Birthday Marks Rocky Path for Alaska Refuge

On Dec. 6, 1960, Fred A. Seaton, then Secretary of the Interior, signed a document that created the Arctic National Wildlife Range, nearly 9 million acres of untamed wilderness in the northeastern corner of Alaska at the time, a brand new state just over two years old.

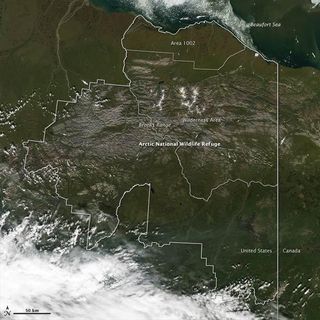

A vast region of mountains, sprawling tundra, rivers, lakes and Arctic coastline, and home to a rich diversity of wildlife, the area is set aside for preservation.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, doubling the size of the Arctic Range to about 18 million acres, establishing 8 million acres of protected wilderness within the region, and changing the name to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), as it is still called today.

In addition, the Act called for wildlife studies and analysis to assess potential oil and gas reserves in a 1.5-million-acre swath along the ANWR's coastal plain on the Arctic Sea.

Because of these competing interests, the ANWR was to become a political football that, once hurled into the halls of Congress, would be snatched back and forth across the aisle for decades to come.

Search for high-stakes answers

Oil was discovered in Alaska's Prudhoe Bay in 1968, and ever since there has been interest in what reserves might lie within the ANWR, about 50 miles (80 km) to the east.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As directed in the 1980 Act that expanded the ANWR, petroleum evaluations were conducted for two years, in 1984 and 1985, in what came to be known as the 1002 area.

"Seismic data were collected by a consortium of companies," said Dave Houseknecht, a research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). "Those data are still marketed by a seismic brokerage firm." (Seismic data can shed light on the potential energy reserves in a region.)

Houseknecht said roughly two dozen oil companies, at one time or another, have purchased rights to the seismic data. The federal government also has access to the information.

However, only one actual exploration well was drilled during the two-year window. "Only Chevron and BP have access to that well," Houseknecht told OurAmazingPlanet.

The resulting data, which are held by BP and Chevron alone, remain a closely guarded secret to this day, Houseknecht said.

No further oil drilling has ever been conducted, and further investigation of the area lies in the hands of Congress.

Whether to open up the area for more drilling has become a regular topic of debate, and estimates of the amount of oil hidden beneath the 1.5-million-acre coastal plain vary.

Houseknecht said the most recent USGS numbers hover around 10 billion barrels of oil. That estimate, last adjusted in 1998, is still based largely on the seismic data collected during the two years of study conducted in the mid-eighties.

Ten billion barrels of oil may sound like a lot, but in 2009 alone, the United States used 6.9 billion barrels of oil, according to federal government statistics.

In addition, oil estimates can change. In October, the USGS drastically reduced its estimates by about 90 percent for potential oil in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska (NPRA), an area about 50 miles (80 km) west of Prudhoe Bay, and about 100 miles (160 km) west of the ANWR.

New data revealed the lion's share of energy reserves in the NPRA are natural gas, not oil.

However, Houseknecht said, it's not possible to then translate those numbers into adjusted oil estimates for the ANWR. Geologically, the regions are vastly different.

"And over in the Arctic Refuge area there are simply no new data available," Houseknecht said. "The reason that we did our updated NPRA estimate is because of all the new data from drilling."

At 50, lookin' good

Even with all the shouting that goes on surrounding the ANWR, it's still possible that many don't know what the remote region actually looks like. A little smaller than West Virginia, the ANWR isn't a bleak, frozen wasteland as one might picture, but is home to a tapestry of ecosystems and a riot of animal and plant life.

ANWR's 19.3 million acres encompass wild rivers, placid lakes, boreal forests, majestic mountains and dramatic coastlines. With no roads or buildings in sight, herds of caribou graze unhindered, grizzlies and black bears ramble, wolves wander and peregrine falcons dive out of the sky.

"What was wonderful is you could stand on a hill and it was just as before," said George Schaller, who has visited the area, first in the 1950s and again, five decades later.

Schaller, a pioneer in the field of conservation, came to the region as a young scientist in 1956. Amid discussions in Washington of setting aside parts of the territory for posterity, Schaller and four others set out to explore the biology of the Alaskan frontier.

"The Arctic Refuge is America's last great wilderness," Schaller told OurAmazingPlanet. "It's something that we should be proud to have as part of our past and as part of our future, without greed or compromise."

Click here to read Schaller's firsthand account of his time at the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge more than 50 years ago, and his return to the area a half century later.

- Image Gallery: Get a Glimpse of Remote Alaska

- Polar Vacation: Conservation With a Twist

- Black Gold: Where the Oil Is

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.

Most Popular