Bittersweet Birthday for ANWR: Scientist Remembers Alaska Refuge Trek

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

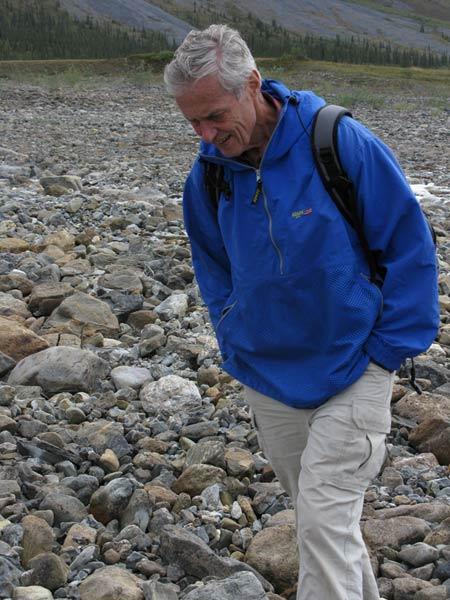

George Schaller has spent a lifetime studying some of the Earth's most iconic animals mountain gorillas, snow leopards, giant pandas in exotic spots across the planet. But one of the first expeditions of his storied career was to a wild corner of Alaska in the summer of 1956.

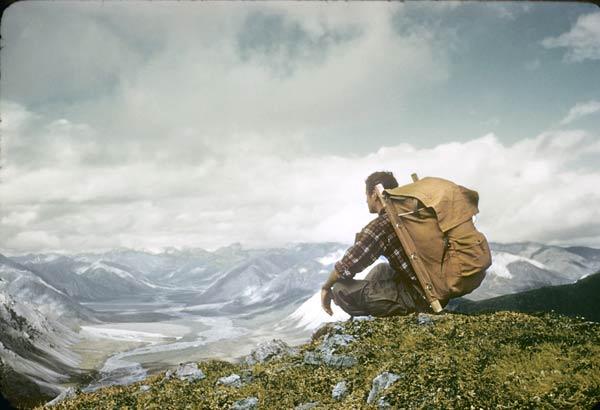

He accompanied Olaus and Margaret Murie, prominent naturalists and champions for the cause of public lands, who proposed to study the biology of the frontier region. For two months that year, in June and July, the team took data on the flora and fauna of the little-explored area, camping within sight of the Brooks Mountain Range.

Schaller and the Muries, along with biologist Bob Krear and ornithologist Brina Kessel, watched caribou wander, ate fresh-caught fish from wild rivers, and heard birds sing at midnight in the pale, late-night sun of the Arctic summer.

Four years later, on Dec. 6, 1960, the region was designated as a protected area by the United States. In the coming decades, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR ) would be a lightning rod for controversy when oil was discovered nearby, in Prudhoe Bay.

Schaller spoke with OurAmazingPlanet about his first trip to the refuge 50 years ago, his recent return, and his thoughts about preserving the area at a time when shouts of "drill, baby, drill," still resound.

How did you end up a part of the expedition that headed out to the area in 1956?

I heard about it, and wrote Olaus Murie that 'Hey, I'm available as an assistant; you only need to feed me!' So he said, come ahead. I had just started grad school at the University of Wisconsin after completing my undergrad at the University of Alaska. I already knew a little of the area because I had worked up there in 1952, so I was very fortunate in that Olaus and Mardy were great people.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They sort of became my mental mentors because they taught me that, yes, we must do good science, but also we must look at what Olaus called the precious intangible values, and that has always stayed with me in all my work over the last 50 years or more.

What was a typical day like?

We'd get up at dawn, and have a little breakfast some cooked oatmeal, a cup of tea and then we decide where we'd go that day. Sometimes we'd go together, for a task or Olaus and I would go and he would talk to me about animal droppings wolf, bear. Other times Brina Kessel and I would watch birds; Bob Krear would go fishing.

Sometimes we'd trickle in for lunch, but often times we'd be gone all day, and in the evening or late afternoon I'd check my mousetraps, skin them and stuff them. For dinner we'd have some noodles or some rice. And after walking all day everybody was usually happy to get to our tents.

Was there anything that surprised you about your experience there?

The nature didn't really surprise me I'd spent four years already in Alaska. But what was wonderful was the companionship, and being with mentors that appreciated the beauty of the area.

We already realized then that it was America's last great wilderness, and something had begun on behalf of saving it for the future. After all, development was proceeding rapidly. I saw oil drilling in 1952. It didn't begin in a big way until 1968, with the discovery of oil at Prudhoe Bay.

I understand you have returned to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge since your first , first in 2006. Had anything changed since your initial visit in the mid-fifties?

What was wonderful is you could stand on a hill and it was as before. At our old campsite, there was still an eagle's nest, and there were no roads, no buildings. That campsite was the same, even some of the same spindly little spruce trees, because things grow very slowly in the cold.

But there were important changes. Glaciers had retreated and brush is moving north this has been well recorded already. The local Gwich'in Indians to whom we talked said they notice things. The ice is thinner on the lakes, the tundra is dry and sometimes burns, which had never happened before. So things are changing for them.

What are some of the most important things you think people should know about the ANWR?

It's remote, it's beautiful, and there's a huge variety of plants and animals there: about 180 species of birds, and animals that the public is interested in, like grizzlies, wolves and polar bears.

The problem is that for years there's been complete misrepresentation to use a kind word about what is up there. It's supposed to be a land of nothing but oil and ice that nobody wants to go to.

But those who go are entranced by it. Albert Einstein said, "I like to think that the moon is there, even if I am not looking at it." That same idea is very true about the Arctic Refuge. It is part of America's natural heritage, and one should keep it for future generations.

Do you have any concerns about the future of the ANWR?

Wilderness has long been a part of America's consciousness. Just look at Teddy Roosevelt's initiatives. And there have always been people concerned about the future. On the other hand, you always have people, like a certain former vice-presidential candidate, that yell "Drill, baby, drill," no matter what the consequences are.

I started out very naïve. I thought when this country had set something aside it would be safe. That obviously is far from the truth, so one has to keep fighting. I certainly hope that President Obama will now make this refuge safe.

Now in his seventies, George Schaller continues to work around the world, studying wildlife. He is a senior conservationist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, and is vice-president of Panthera, an organization dedicated to saving the planet's big cat species.

- 50th Birthday Marks Rocky Path for Alaska Refuge

- Polar Vacation: Conservation With a Twist

- Black Gold: Where the Oil Is

Reach Andrea Mustain at amustain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaMustain.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus