Weird Way Lyme Disease Bugs Avoid Immune System

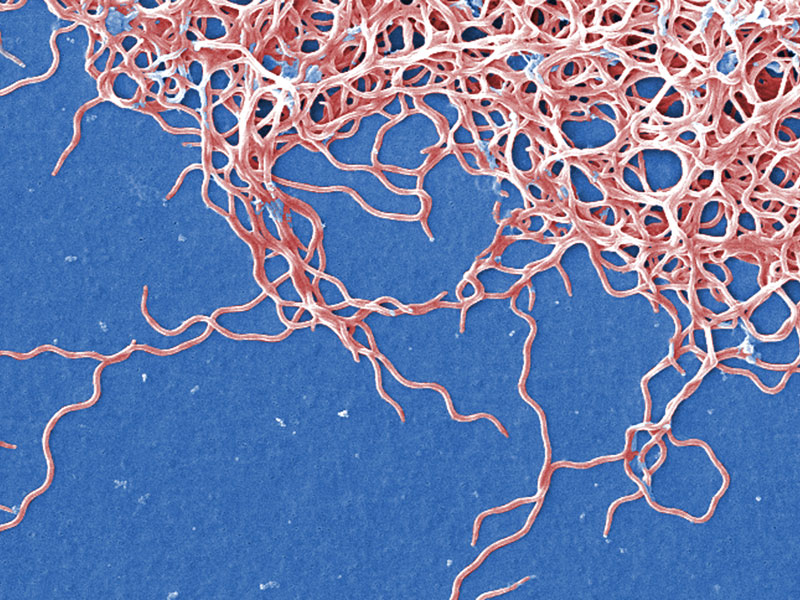

The bacterium that causes Lyme Disease substitutes manganese for iron in its diet, a new study finds. The pathogen is the first known organism to live without iron.

This talent helps the pathogen evade the immune system, which often acts against foreign invaders by starving them of iron.

Lyme disease is transmitted by tick bites and can cause fever, fatigue, headaches and rashes. If not treated promptly with antibiotics, the disease can start to attack the circulatory and central nervous systems, causing shooting pains and numbness as well as cognitive difficulties.

Now, researchers have found that to cause Lyme disease, the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi requires a large supply of manganese, which it uses instead of iron to make an important enzyme. The discovery could open new doors for the treatment of Lyme disease, said study researcher Valeria Culotta, a molecular biologist at the John Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health.

"The only therapy for Lyme Disease right now are antibiotics like penicillin, which are effective if the disease is detected early enough," Culotta said in a statement. Penicillin acts by attacking the bacteria's cell walls, she said, but some forms of the bacteria don't have cell walls.

"We'd like to find targets inside pathogenic cells that could thwart their growth," Culotta said.

Researchers have known since 2000 that Borrelia doesn't have the genes it would need to make iron-containing proteins. But no one knew what they were using instead. Culotta and her colleagues used specialized equipment to measure metal-containing proteins in Borrelia, detecting metal content down to parts per trillion.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that the bacterium substitutes manganese for iron, particularly in defensive proteins that help protect the pathogen against the immune system.

The researchers now plan to map out all of the metal-containing proteins in Borrelia and plan to learn how the bacteria acquire manganese from their environment. The manganese mechanism may be a chink in the bacterium's armor that humans can exploit, Culotta said.

"The best targets are enzymes that pathogens have, but people do not, so they would kill the pathogens but not harm people," she said.

The researchers reported their findings today (March 22) in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.