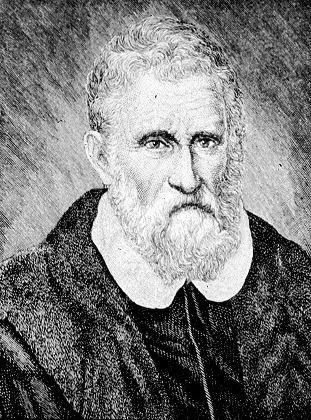

Marco Polo: Facts, Biography & Travels

The story of his journey is told in "Il Milione" ("The Million"), commonly called "The Travels of Marco Polo." Polo's adventures influenced European mapmakers and inspired Christopher Columbus.

In Polo's day and even today, there has been some doubt about whether Polo really went to China. However, most experts agree that he did indeed make the journey.

Early life

Marco Polo was born around 1254 into a wealthy Venetian merchant family, though the actual date and location of his birth are unknown. His father, Niccolo, and his uncle Maffeo were successful jewel merchants who spent much of Marco's childhood in Asia. Marco's mother died when he was young; therefore, young Marco was primarily raised by extended family.

"The merchant families were the movers and shakers of commerce and government in medieval Venice," Susan Abernethy of The Freelance History Writer told LiveScience. They expanded long-distance trade and people began to expect accessibility to the foreign goods they brought. Merchants, like the Polo family, became increasingly wealthier.

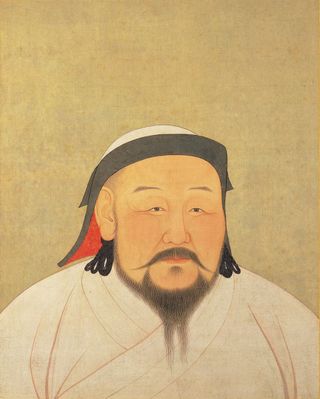

The Polo brothers went as far as China, then called Cathay, during their travels. They met the Mongol leader, Kublai Khan, at his court in Beijing. Kublai Khan, grandson of the great conqueror Genghis Khan, expressed interest in Christianity and requested that the Polo brothers return to Rome to speak to the pope on his behalf. Khan wanted the pope to send the Polo brothers back to Beijing with holy water and 100 learned priests.

"Khan was an exceptional ruler for many reasons," said Abernethy. "He opened up the Mongol and Chinese empires to travelers and traders. He patronized scholars, scientists, astronomers, doctors, artists and poets. Khan himself was an expert in Chinese poetry. In turn, Khan was able to take advantage of the knowledge of these foreigners in enormous projects such as efforts in water management and hydraulic engineering and warfare and siege engineering and other endeavors." The Polos were one family that Khan trusted and learned from.

When Marco was 15, his father and uncle returned home. Though the pope did not grant their request, the Polo brothers decided to return to Asia. This time, they took 17-year-old Marco with them.

The slow road to China

The party sailed south from Venice across the Mediterranean to the Holy Land. They had brought two friars — the best they could do for Kublai Khan's request — but upon getting a taste of difficult travel life, the friars turned back. The Polos continued, traveling primarily overland and swinging north and south through Armenia, Persia, Afghanistan and the Pamir Mountains. Then, they cut across the vast Gobi Desert to Beijing.

The journey took three or four years and was rife with hardships and adventure. Marco Polo contracted an illness and was forced to take refuge in the mountains of northern Afghanistan for an extended period of time. Polo described there being "nothing at all to eat," in the Gobi Desert. Nevertheless, young Marco Polo enjoyed a keen sense of adventure and curiosity, taking in the sights, smells and cultural phenomena with wonder.

In Xanadu, with Kublai Khan

Finally, the Polos reached Beijing and met Kublai Khan at the summer palace, Xanadu, a glorious marble and gold structure that enchanted young Marco. Khan happily received the Polos. He invited them to stay and for Niccolo and Maffeo to become part of his court. Marco immersed himself in Chinese culture, quickly learning the language and taking note of customs. Khan was impressed and eventually appointed Marco the position of special envoy.

" I suspect Marco was educated and erudite and charming," said Abernethy. "He learned to speak four languages and exhibited a great curiosity and tolerance regarding his surroundings and the people he met with. Khan recognized his talents … Polo was devoted to serving the Emperor."

This position allowed Marco to travel to the far reaches of Asia — places like Tibet, Burma and India; places that Europeans had never before seen. Over the years, Marco was promoted to governor of a great Chinese city, to the tax inspector in Yaznhou, and to an official seat on the Khan's Privy Council.

"Khan provided Marco and his family with a 'paiza' — a gold tablet which authorized him to make use of a vast network of imperial horses and lodgings. This in effect was an official passport making the Polos honored guests of the emperor and allowing them to travel freely throughout Asia," said Abernethy.

Through it all, Marco Polo marveled at China's cultural customs, great wealth and complex social structure. He was impressed with the empire's paper money, efficient communication system, coal burning, gunpowder and porcelain, and called Xanadu "the greatest palace that ever was."

Return home

The Polos stayed in China for 17 years, amassing vast riches of jewels and gold. When they decided to return to Venice, unhappy Khan requested that they escort a Mongol princess to Persia, where she was to marry a prince.

During the two-year return journey by sea across the Indian Ocean, 600 passengers and members of the crew died. By the time they reached Hormuz in Persia and left the princess, just 18 people remained alive on board. The promised prince, too, was dead, so the Polos had to linger in Persia until a suitable match for the princess could be found.

Eventually, the Polos made it back to Venice. After being gone for 24 years, people did not recognize them and the Polos struggled to speak Italian.

Legacy

Three years after returning to Venice, Marco Polo assumed command of a Venetian ship in a war against Genoa. He was captured and, while being held in a Genovese prison, he met a fellow prisoner, a romance writer called Rustichello. When prompted, Polo dictated his adventures to Rustichello. These writings, written in French, were titled "Books of the Marvels of the World," but are better known in English as "The Travels of Marco Polo."

"Polo's book was what we would call a "blockbuster hit" and made Marco Polo a household name.," said Abernethy. "At first, many viewed the book as fiction, more like a chivalric fable with its seemingly tall tales and descriptions of fantastical animals. Many copies of the book were created and it was translated into several languages. It was only after Polo's death that people realized the book contained the truth about his travels and what he witnessed."

Additionally, some readers questioned Polo's reliability, possibly leading to the book's popular Italian title, "Il Milione," short for "The Million Lies." Some questioned whether Polo even went to China or if the entire thing was hearsay.

There were several reasons people doubted the veracity of the book. One was its writing process. Polo dictated from his copious notes, and Rustichello (or Rusticiano), who was an author of some renown "may have embellished the story," said Abernethy.

The publishing process of the time could also lead to truths being exaggerated or changed. The book came about before the printing press, and hand-copied manuscripts are subject to human error and willful changes, according to Abernethy.

"There are what seem to be some glaring omissions," she said. "Polo doesn't mention the Great Wall of China, foot binding, tea or the use of chopsticks. However, none of this is unusual. There are other chroniclers throughout history who omitted obvious information from their writings."

It is also possible that Polo knowingly embellished or recounted stories he heard from other travelers. "Some of the tales seem far-fetched and it's clear Polo didn't witness some of the related information," said Abernethy. "Polo may have been somewhat naïve about what he was witnessing and seen everything through Western eyes, creating discord in the narrative. He may also have recounted stories he heard from other travelers."

That's his story and he's sticking to it

Polo stood by the book, however, and went on to start a business, marry and father three daughters. When Polo was on his deathbed in 1324, visitors urged him to admit the book was fiction, to which he famously proclaimed, "I have not told half of what I saw."

Though no authoritative version of Polo's book exists, researchers and historians in the subsequent centuries have verified much of what he reported. It is generally accepted that he reported faithfully what he could, though some accounts probably came from others that he met along the way.

"It seems the preponderance of the evidence reveals that Polo did indeed visit China," said Abernethy. "He brings to light detailed information on the currencies used, including paper currency. He mentions the use of burning coal. The data he provides on salt production and revenues show a meticulous familiarity on the subject. Many of the place names he gives in the narrative have now been identified. His description of the Grand Canal of China is highly accurate. Indeed, the premise that he didn't visit China creates more questions than it answers."

The information in his book proved vital to European geographic understanding and inspired countless explorers — including Christopher Columbus, who, it is said, took a copy of Polo's book with him in 1492.

"About fifty years after Polo's death, his work began to be utilized in the making of maps," said Abernethy. "Cartographers employed the descriptions of his travel routes and the names and terms he used to designate locations in the drawing of their maps."

Who knew?

Marco Polo did not introduce pasta to Italy. The dish had already existed in Europe for centuries, according to History.com.

The claim that he brought ice cream to Europe is also disputed. A French ice-cream master, Gerard Taurin, argues that Polo did introduce ice cream from China. According to the International Dairy Foods Association, Polo returned with a recipe that resembled modern-day sherbet, and this recipe may have evolved into ice cream in the 16th century.

Polo was one of the first Europeans to see a rhinoceros. However, he thought they were unicorns.

Some scholars think that Polo was born on the island of Korcula on the Adriatic coast, in what is today Croatia, according to a 2011 article in the Telegraph. According to this theory, his father was a merchant from Dalmatia named Maffeo Pilic, who changed his last name to Polo when he relocated to Venice.

In 2011, Italy objected when a museum dedicated to Polo in the Chinese city of Yangzhou was opened not by Italian diplomats but by a former president of Croatia, Stjepan Mesic. Mesic described Polo as a "world explorer, born in Croatia, who opened up China to Europe."

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.