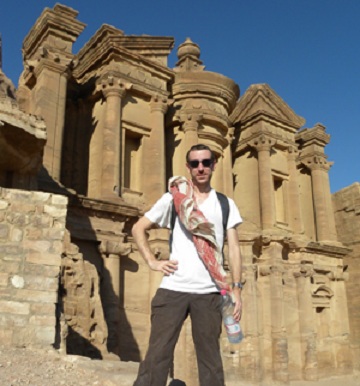

Ancient Traces of Terrace Farming Found Near Petra

The ancient city of Petra, which was carved into the desert cliffs of modern-day Jordan, might look inhospitably bone-dry today, but new archaeological evidence shows that its first-century inhabitants took advantage of what little water reached the region to farm wheat, grapes and possibly olives just outside the city.

Researchers say extensive terrace farming and dam construction in an agricultural suburb north of Petra began about 2,000 years ago — sometime before the Romans took control of the city from the Nabataeans in A.D. 106. The Nabataeans were a people who wrote using an Aramaic language and controlled caravan trade throughout the region. (A small number of the Dead Sea Scrolls were apparently written in Aramaic.)

"No doubt the explosion of agricultural activity in the first century and the increased wealth that resulted from the wine and oil production made Petra an exceptionally attractive prize for Rome," researcher Christian Cloke, a doctoral student at the University of Cincinnati, said in a statement. "The region around Petra not only grew enough food to meet its own needs, but also would have been able to provide olives, olive oil, grapes and wine for trade. This robust agricultural production would have made the region a valuable asset for supplying Roman forces on the empire's eastern frontier."

The researchers involved in the Brown University Petra Archaeological Project (BUPAP) say they found evidence of quite impressive systems to dam riverbeds and redirect rainwater from the region's brief and torrential winter downpours to the hillside farming terraces north of the city. Meanwhile, Petra's inhabitants took advantage of the broad watershed of sandstone hills that naturally guided water to the city center by building a complex system of pipes and channels to direct water to underground cisterns for storage.

"Perhaps most significantly, it's clear that they had considerable knowledge of their surrounding topography and climate," Cloke said. "The Nabataeans differentiated watersheds and the zones of use for water: water collected and stored in the city itself was not cannibalized for agricultural uses. The city's administrators clearly distinguished water serving the city's needs from water to be redirected and accumulated for nurturing crops."

These initial conclusions from the first three seasons of BUPAP fieldwork promise more exciting discoveries about how the inhabitants of Petra cultivated the outlying landscape and supported the city's population, the researchers noted. The presence of highly developed systems of landscape modification and water management at Petra also offer insight into geopolitical changes and Roman imperialism.

Cloke will present the findings Jan. 4 at the Archaeological Institute of America annual meeting in Seattle.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.